Before the advent of colonial rule India was a world leader in the production of cotton cloth and in growing a diversity of cotton crop varieties which provided the base for this cotton cloth. India’s cotton fabrics of diverse forms and colors were in demand even in distant countries of the world. This provided the base for sustainable livelihoods of a vast number of farmers, spinners and weavers and other artisans providing a wide range of related services, including making various implements, looms and colors. In particular highly skilled weavers with the distinct identity of their creations became famous over vast parts of the country and abroad.

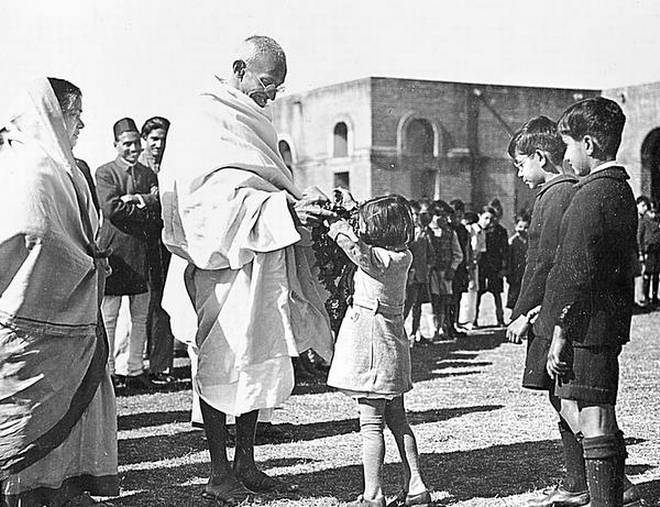

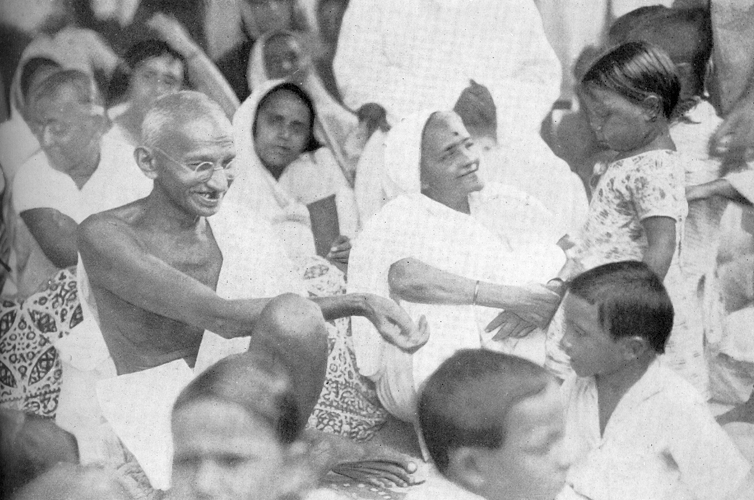

This rich heritage was destroyed by colonial rulers as they wanted to replace India-made cloth with British-made cloth. Mahatma Gandhi understood how big a blow this was to the livelihood base of Indian masses and so he responded with a mass movement for keeping alive hand-spun, hand woven cloth (khadi) which became a very respectful part of the freedom movement.

Unfortunately we have not been able to protect this legacy properly and adequately in more recent years. Let me mention at least three reasons for saying this.

Displacement of the rich diversity of cotton varieties

First and foremost, the rich diversity of indigenous cotton varieties have been displaced almost completely in many areas and even if these may have survived in a few areas perhaps, their huge disappearance from our farms cannot be denied. Thus while earlier hundreds of generations of farmers had been preserving traditional varieties of cotton most suitable for various parts of our country and adding to them, within a few years these were almost entirely displaced from our farms and, horror of horrors, replaced by GM varieties, a known threat to environment, health and sustainable farming. Thus the indigenous crop base of cotton cloth production was badly disrupted.

Of course this was also harmful for hand-spinners and handloom weavers as the indigenous varieties were better suited to them and they had been using these for a long time.

While the government continued to promote Khadi and while it is good that India still leads the world in terms of the hand-spun, hand-woven cloth or khadi cloth produced and used here, before a lot of credit can be claimed for this, I would like to raise a few questions.

In the case of how much khadi cloth can it be clearly shown where the hand spinners who spun the yarn for this cloth live and work, and that they were promptly provided a wage that can be called a reasonable source of livelihood? Are there several instances of Khadi institutions facing either genuine difficulties of survival, or of government help not reaching them in time, or of dishonest persons trying to grab institutions and their land of increasing value in cities? Are products of dubious institutions or very commercial minded ones getting more place in sales records while many sincere khadi workers may be in distress? Is use of khadi increasing among ordinary people including villagers?

Anyone seeking honest answers to these questions will realize that not all is well with the khadi sector. I am saying this not at all as a critic. Instead I am saying this very reluctantly and sadly as a long-time friend of the khadi sector.

However what cheers me up is that while visiting small towns and villages I still meet some people who steadfastly remain as dedicated to khadi as ever. It was even more of a delight to meet such a dedicated supporter of Khadi recently in N. Delhi in the form of former Rajya Sabha member (he completed his tenure very recently) Aneel Hegde. He told me that he had specifically visited those committed farm scientists who have saved indigenous seed varieties of cotton. He got seeds of these varieties from them and grew them on farms of farmers known to him, and used this cotton to get his hand-spun, hand-woven clothes which he was wearing the day I met him with great pride. In Parliament he was again and again trying to speak and raise questions about the well-being of khadi sector, about hand spinners and handloom weavers, about the problems of GM crops. Close to his homes in Bihar and Karnataka he had local artisan shoemakers who made shoes for him, but in Delhi he had to chase and convince a shoe repairman or mochi to make his shoes, and when the mochi made the first pair of shoes for him the artisan himself was so happy with the result that he told him that in future he should always come to him for his shoes.

The reason for all this persistence, Aneel Hegde told me, is that all my life I have worked for the protection of the small artisan and small enterprises, and so when as a consumer I have a choice to make, I want to make a choice that will give satisfactory and creative livelihood to a small artisan or craftsperson.

This kind of thinking on the part of more and more consumers is what Gandhiji called the true spirit of Khadi and this true spirit of Khadi needs to grow for the real success of khadi.

Bharat Dogra is Honorary Convener, Campaign to Save Earth Now. His recent books include Man over Machine, Protecting Earth for Children, When the Two Streams Met and A Day in 2071.