VIEWPOINT

The need of the hour is greater and equal allocation of resources aimed at equalizing the pre-existing disparity among central and regional universities, and the creation of more public-funded universities to facilitate entry of the last person in line into the regular mode of higher education.

Mohammad Bilal and Dinesh K. Verma – Research Scholars, Ambedkar University, Delhi and Activists in Krantikari Yuva Sangathan (KYS).

The University Grants Commission (UGC) on March 20, 2018 announced that it would be granting ‘autonomy’ to 60 universities and colleges across the country. This autonomy would be based on their ranking in a categorized hierarchy of educational institutions.

The institutions granted autonomy would be free to devise courses, decide on fees to be charged as well as the salaries of the staff employed. In other words, the UGC would be withdrawing its monitoring role over such institutions made ‘free’ to achieve ‘excellence’. However, resistance has surfaced following this announcement by the UGC.

Many teachers and students’ organizations have argued that autonomy is actually a model for the withdrawal of public funding to institutions of higher education. Their concerns are corroborated by the fact that it has become a dominant trend with successive governments constituting policy-planning committees/commissions on education which consist of capitalists and corporate lobbyists.

One such commission that has had much say in the recent policy shift in education matters is the National Knowledge Commission (NKC). In its report, titled Report to the Nation 2006–2009, the NKC argued against the existing structure of affiliated colleges for undergraduate education, saying that: ‘…First, it imposes an onerous burden on universities which have to regulate admissions, set curricula and conduct examinations for such a large number of undergraduate colleges. The problem is compounded by uneven standards and geographical dispersion.

Second, the undergraduate colleges are constrained by their affiliated status, in terms of autonomy and space, which makes it difficult for them to adapt, to innovate and to evolve. The problem is particularly acute for undergraduate colleges that are good, for both teachers and students are subjected to the ‘convoy problem’ insofar as they are forced to move at the speed of the slowest…In fact the design of courses and examinations needs to be flexible rather than exactly the same for large student communities’ (p. 70; emphasis added).

Theoretically, the concept of autonomy for affiliate colleges has been in existence for some time now. In 1964 the Mahajani Committee on Colleges, for example, took the position that ‘one of the practical methods’ of improving the standard of higher education in India was by selecting a few colleges ‘on the basis of past work, influence, traditions, maturity and academic standards and give them what might be called for want of a better phase an “autonomous” status with freedom to develop their personalities’.

Even the National Policy on Education for 1986 stated: ‘Autonomous colleges will be helped to develop in large numbers until the affiliation system is replaced by a free and more creative association of universities and colleges’. The first such college came into existence in Tamil Nadu in 1978 and the number started growing slowly. The process was given a spurt with the setting in of neoliberal economic reforms in the early 1990s.

In 1994 the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) was set up to determine grades for institutions based on their performance. There was an apprehension in the beginning itself that the grading system would later be used to allocate differential funds to different institutions, which has now become a reality.

In order to analyze the implications behind this step, a brief look at the proposal would be pertinent. As per the MHRD notification issued in the Gazette of India in February 2018, colleges and universities with grades over 3.51 out of four will be classified as Category I and get maximum autonomy.

They can start new courses, centers, campuses and research parks, enter into collaborations with other universities, recruit foreign faculty and admit foreign students without having to seek permission from the UGC, “provided no demand for fund is made from the government”. For “external review”, they will have to only send reports to the Commission. Category II institutions, with accreditation scores from 3.26 to 3.5, will enjoy much the same freedoms but, if required, they will be reviewed by representatives from Category I institutions.

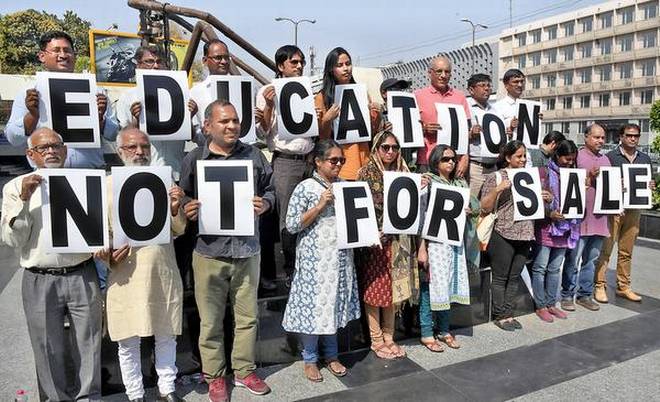

The disquiet among teachers and students of several public-funded universities regarding the government’s decision is based on several factors. The general argument is that this pushes colleges/universities to generate their own resources through self-financed courses, which shall translate into fee hikes. This process will eventually culminate in the state shedding its responsibility of subsidizing higher education, i.e. treating it as a public good, as a public service, rather than as a commodity.

However, despite the fact that there is an overall consensus in the teaching community that the autonomization would be wreaking havoc on hitherto publicly-funded higher education institutions, a very crucial element of the entire process has been downplayed.

The current form of arguments against dismantling of public-funded higher education neglects the question of the exclusivity and elitism imbibed by educational institutions in the focus of the current controversy. It is an indisputable fact that the institutions we seek to save from the axe of autonomy have minimally catered to deprived sections of students.

The high cut-offs for admissions ensure time and time again that these students do not make it to these higher education institutions. Like it or not, the education system in our country is highly hierarchical and already nurtures exclusion of students from marginalized and vulnerable sections and communities.

The education system in post-colonial India has been exclusionary since its inception. The education commissions instituted by Indian governments such as University Education Commission (Radhakrishnan Commission) 1948, and Indian Education Commission (Kothari Commission) 1964 made certain recommendations, which on being incorporated, came to perpetuate a hierarchy in higher education. A few ‘centres of excellence’ were envisaged, which have been catering largely to privileged youth, who have thereby been enabled to land well-paying, professional jobs. A large section of youth, however, have been simultaneously relegated to vocational courses (polytechnique and industrial training) or to distance learning; and thereby have been skilled for arduous, menial and less remunerative occupations in the Indian economy.

The underlying logic of the exclusivity so devised has continued to affect the youth of deprived sections, who in reality constitute a large majority of youth in the country. They have restricted their entry into premier institutions and by extension into well-paying segments of the Indian job market.

The hierarchy is as follows: on the top are the central universities, several of which have been selected for being made ‘autonomous’. These apex institutions are directly funded by the central government and are among the most-well functioning institutions in our country. The entry into them is highly competitive. The fees charged at these institutions are highly subsidized, and consequently, they become the choice destination of students coming from privileged sections.

On the next rung are the regional universities which are funded by the governments of the respective states. These institutions are generally known for crumbling infrastructure and a decrepit educational atmosphere, which is the fallout of insufficient funding and apathetic attitude of state governments. These institutions have come to cater to the educational needs of mostly the lower middle class and underprivileged strata of youth for whom expending money on studies at premier universities is financially impossible.

A new segment/rung in the hierarchy has emerged in the recent years, namely the correspondence/distance-learning mode of education offered by public-funded universities, including the premiere ones. The distance-learning mode caters to the vast number of youth coming from deprived, underprivileged sections of society, who fail to get admission in the regular mode of college education.

In most metropolitan cities, this segment is the biggest component of the university system and it amounts to ten times the number of students enrolled in formal, regular courses of these universities. Contrary to the statistics cited by the successive governments of the growing percentage of youth enrolled in higher education (Gross Enrollment ratio for 2016-17 is 25.2%), the correspondence mode is the chief factor behind such an increase.

The quality of education imparted through the correspondence mode reeks of neglect and discrimination due to low-quality instruction, general apathy of teachers and miniscule number of classes. To take an example, Delhi University’s (DU) School of Open Learning enrolls thrice the number of students than those enrolled in regular courses.

Most of the students come from poor, deprived and marginalized sections of society. A large majority of these students invariably hail from Delhi government’s funded schools whose quality has crumbled in recent decades, and so expectedly these youth fall behind in the competition for the miniscule number of seats in DU’s undergraduate courses. Despite most of them being products of government schooling, these youth are given no preference and are made to compete for seats in DU’s public-funded colleges. Their competitors are elite students coming from the top private schools from across the country. This process or apartheid rather, is repeated with an increased intensity every year. The same trend can be witnessed in correspondence/distance-learning departments of other premier universities.

Clearly, such an educational setup in higher education begs the need of urgent reforms. But, reforms presently proposed by UGC in accordance with the Central government’s plan only further buttress the already highly exclusive nature of higher education in India.

Instead of bringing in reforms aimed at improving the access to higher education for marginalized youth of our country, and making higher education accessible and inclusive, in recent years there have been attempts by successive governments to make education a marketable commodity conceived not as the right of youth but as a payable service. India’s participation in General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) talks in Nairobi in 2015 can be viewed as the backdrop of such initiatives.

The talks made it incumbent upon the participating countries to effectively privatize public-funded institutions so as to open the field of education to private players. The Central government has gone on to propose/implement several measures which amply reveal its blatant attempts at privatizing higher education sector. Mushrooming private universities and educational centers of foreign universities in many Indian cities is further proof of this. The slashing of funds for higher education in the most recent Union budgets, the efforts to cut scholarships for research scholars, and growing trend of partially funding public institutions, point towards attempts at privatization. The granting of autonomy to premier institutions logically follows in such a schema.

Autonomy has then to be resisted for its inability to reform the system of higher education we have at hand. It is to be resisted as a move towards privatization of higher education and as a measure that further grants centers of excellence the space to exercise the right to exclusion. Educational reforms are those measures alone which envisage an education system that brings quality higher education within the reach of more and more marginalized and deprived sections of youth, hitherto those unable to enter higher education or languishing in correspondence mode.

Today, the need of the hour is greater and equal allocation of resources aimed at equalizing the pre-existing disparity among central and regional universities, and the creation of more public-funded universities to facilitate entry of the last person in line into the regular mode of higher education.

http://https://youtu.be/qbP0xDY8Gcg

***