By Ramesh Savalia

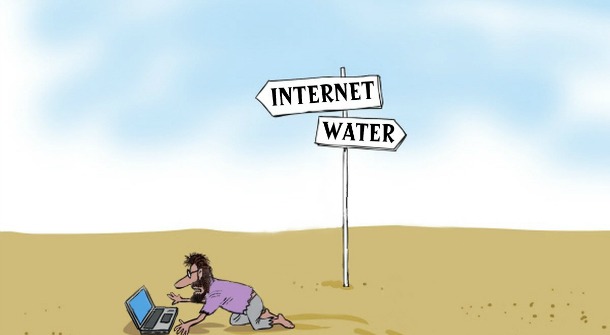

Last several decades have witnessed India, like many other emerging economies, facing unique environmental, social and ethical challenges. Natural resources, including biological diversity which is the bedrock of the livelihood of the rural poor, are under severe pressure due to rapid industrialization and urbanization. This has enhanced economic disparity, resource use and conservation conflicts, and has disrupted social harmony. Traditions in India are essentially characterized by the philosophy of coexistence – ‘living together’ and ‘the earth as one family’ – but the modern ‘utilitarian view’ of life is resulting in individuals becoming increasingly more self-centered, less tolerant and alienated from nature, their own culture and traditions.

The present approach of education that gives low status to traditional knowledge has resulted in a loss of knowledge passed through oral tradition. The present model of school education lacks adequate linkage with real life and livelihood of the surrounding area. Another lacuna of the school system is the lack of experience-based learning of local biodiversity in the curriculum. The linking of conservation, experience-based education and extending experiment-based learning to the community level need to be supported and strengthened.

The revival of one of the very sound traditions and culture of co-existence with nature and all its creations is at the heart of the concept of ‘Project Sanjeevani’. Through its bottom up, participatory and inclusive approach the project has created an environment on the school campus, which is conducive for young students to learn to live in harmony and reconnect with their roots.

The Sanjeevai Initiative:

‘Sanjeevani’ in Gujarati language as well as in Sanskrit means ‘a plant that has power to revitalize, regenerate life’. The project Sanjeevani has strived to revitalize secondary schools through facilitating community-school linkages for Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). Sanjeevani is an effort to re-define and re-establish the linkages among schools, society, traditional knowledge, culture and environment. Through its process of students interacting and seeking knowledge from community – especially women, farmers, traditional healers and their own parents/grandparents, not just helped the young generation connect with the local biodiversity, it also created a bridge between two generation, created respect among children for farmers, women and tribal community and the traditional wisdom they possess.

The rich medicinal plant biodiversity of the sub-humid ecological region of South Gujarat’s tribal belt is threatened by forces such as lack of awareness and alternatives to forest-based livelihood, a marked preference for quick fix development approaches, and increasing biotic pressure. In a similar manner the semi-arid ecological region of Gujarat’s Saurashtra region is threatened by intensive market-driven agriculture, destruction and fragmentation of habitats as a result of deforestation and rapid industrialization, lack of valuation of biodiversity, and non-sustainable extraction of forest resources for commercial purposes. The Sanjeevani project focuses on developing the potential of schools at these two locations which represent the major ecological regions of Gujarat.

Sanjeevani aimed to integrate the knowledge of biodiversity and medicinal plants into school programmes, as well as to develop a system of their cultivation on the school campuses while creating awareness of and respect for traditional wisdom. It also aimed to establish a network of academics, scientists, traditional healers, farmers and other PBSs for knowledge enhancement. The network was also expected to contribute in initiating demonstrable sustainable livelihood projects so as to improve the quality of life in rural areas and help avoid livelihood-related conflicts and stress.

But Sanjeevani is not just a project; it is a ‘way of thinking’. It leaps over the confines of the tangible – medicinal plant diversity conservation and education – and strives to encompass the core of education for sustainable development (ESD), which is made up of intangibles: the values of living together, tolerance, reverence for nature, respect of natural and cultural diversity, and social equity.

Post Basic Schools (PBSs), which are residential secondary education institutes based on the Gandhian philosophy of providing to the rural poor an experiential education that integrates the 3H (Heart, Head and Hand), are the primary stakeholders of ‘Project Sanjeevani’. A very strong focus on what we can now term as sustainable development was at the core of the PBS curriculum. Today, however, these institutes, though physically located in rural areas, have little to do with local realities. This unfortunate disconnect has negated the very purpose of their existence. Sanjeevani was an innovative intervention to redirect the schools to their raison d’etre. Through the schools the project involved other stakeholders as well, especially women, farmers, traditional healers, parents of the students, senior citizens, local NGOs, Aayurvedic Universities and research institutes. The project partnered with 10 PBSs across the state of Gujarat, India and worked closely with 20 villages.

The linking of conservation, experience-based education and extending experiment-based learning to the community level makes Sanjeevani a suitable model of Learning through Doing. Sanjeevani is not just a project; it is a ‘way of thinking’. It leaps over the confines of the tangible – medicinal plant diversity conservation and education – and strives to encompass the core of Education, which is made up of intangibles: the values of living together, tolerance, reverence for nature, respect of natural and cultural diversity, and social equity.

Each of the 10 partnering schools developed a ‘Biodiversity Conservation Resource Area (BCRA) including a Sanjeevani Garden’ (medicinal plants garden) which serves as an integrated nature learning facility for the community as well as the school. The essentially of the project was to evolve a replicable model of community oriented action project for schools that can provide much needed real life association and holistic learning opportunity for students, teachers and neighboring community.

Process of implementation, was not a rigid, top-down, standardized straitjacket. Rather, it comprised open-ended, bottom-up processes in which students, teachers, community members including farmers and traditional healers took decisions in collective and participatory manner. Process of creation of BCRA is also an example of collaborative experiential and contextual learning. Students and teachers learnt farming techniques from the barefooted scientists- the farmers. BCRA is conserving local biodiversity and associated traditional knowledge in-situ. It has now become an important source of traditional knowledge, and also medicinal plants for further use in the community as well as for cultivation.

Some of the key implementation processes and features in the context of learning through doing:

- A number of learning opportunities for teachers, students and community were created in various forms such as exposure tours, lateral learning through dialogues and experience sharing, contemplation camps, field visits, demonstrations, thematic workshops, and interactions with experts/practitioners and so on for different stakeholders.

- Biodiversity and traditional knowledge survey in which students surveyed nearby villages along with village adults, biodiversity experts and traditional healers to list species found, note the richness of local medicinal plant diversity, met women and seniors to understand the common diseases in the area and how they have been using local medicinal plants to treat them.

- Participatory Planning and Development of BCRAs as an Open Nature School for Teachers, Children and Community. Students, teachers together – with the help of an architect – evolved the design of BCRA based on three values – conservation value, educational value and aesthetic value. BCRA design was evolved through an intensive and participatory process involving children and teachers.

- Scientific knowledge of agricultural and Aayurvedic universities and the needs of the local communities as well as of the schools were combined through a vigorous study by the schools and the project team together, which became the basis for determining the species to be planted.

- The children participated in all the processes: designing, layout, soil-water analysis, deciding the species for plantation based on needs, climatic conditions and local soil-water quality, sourcing quality saplings and comparative rate study, preparing plantation beds, plantation, nurturing plants, watering, mulching, bio-pest controls, preparing the signage system, designing walkways, seating arrangements, open classroom, activity areas and so on. All these processes were highly educative in the context of living together, learning from each other, and working towards a collective goal of acquiring a better understanding of their own roots, lives and livelihoods.

- This honed multiple skills – technical as well as socio-personal. Students, for instance, were involved in structural work so that they had the opportunity to learn technical aspects related to low cost and sturdy structure design and masonry skills. At the same time they became more sensitive towards workers and learnt dignity of labor.

- Linking experience-based education with conservation and extending this learning to communities, combined with a process-oriented approach in execution is one of the highly innovative features for learning of children.

- Involving students, teachers and farmers in all the processes in a participatory, bottom-up approach helped create collective ownership, which is a key factor behind this success.

- Identification of local plant biodiversity by students and teachers with the help of farmers, women, traditional healers and other family members, helped in identifying plants that are needed to be conserved as well as created interest among students to know and conserve this biodiversity and associated knowledge.

- Making the BCRA a platform for lateral learning and outreach, thus opening up the doors of the schools to the village grownups and turning the schools into institutes for rural communities in the true sense.

- The involvement of traditional healers in the project lent the project a sense of practical importance encouraging the students to respect traditional wisdom.

Learning the Treasure Within through Sanjeevani

In tune with the UNESCO report recommendation of ‘Learning the Treasure Within’, the development of BCRA served as ‘work experience’ opportunity wherein holistic learning was facilitated through various processes. Thus, throughout the Sanjeevani project capacity-building of the students was not limited to a few classroom sessions or specific workshops but it became a continuous process finely interwoven with day-to-day activities. Some examples are

- Biodiversity survey, field trips, nature camps to identify biodiversity and inculcate respect for traditional wisdom.

- Designing and developing BCRA involved students at every step, which honed multiple skills – technical as well as socio-personal. Students, for instance, were involved in structural work so that they had the opportunity to learn technical aspects such as bricks needed, cement-sand mixing ration, preparing RCC, cost of different materials, concepts that can make structures sturdy and low cost. At the same time they became more sensitive towards the workers and learnt dignity of labor. In another interesting example, a workshop was organized for students to design seating arrangement in BCRA using waste ceramic material. In the process they learnt about waste as a resource.

- While planning species to be planted the students had to reckon with the needs of the community and also of their school, for which they had to understand various aspects such as medicinal properties, nutritive value, using different species for preventive and curative treatment and so on.

- Most importantly, they learnt to innovate, be creative and be sensitive towards others. One such example was in the water-scare region where one plant was allotted to each student for watering through his/her daily activities such as washing hands and utensils (avoiding soap or other chemicals). Developing seeds bank, resource corner etc in the Resource Centre also enhanced their knowledge, creativity and capacity to learn.

Evolving BCRA as a nature school and school’s community outreach centre

- Teachers using BCRA as an educational resource, enabling students to observe, experiment and monitor various aspects of plant growth such as which types of plants grow better and where, thereby understanding taxonomy and morphology, soil science, water conservation and so on.

- Visits by neighboring schools for educational tours.

- Demonstration plots for organic farming, bio-composting, bio-pest control, vermi-wash, planting of medicinal plants on farm boundaries, drip irrigation, soak-pits etc on BCRA.

- A Sanjeevani Resource Centre has been set up on each project school campus without having any specific budgetary provision! These Centres have come up as a result of the enthusiasm of the teachers, students and communities. They have prepared and collected a range of material such as exhibitions, articles, books, photographs, case studies, and a variety of wild seeds. Looking at their passion we also searched and provided more than 300 relevant books and audio-video aids. Schools allotted separate rooms to house the Sanjeevani Resource Centres which are full of information that captures every one’s interest.

- Participating in community fairs, organizing school awareness and community awareness programmes involving students and teachers.

How Sanjeevani changed teaching and learning

It is difficult to describe the kind of interest and engagement the children had in every aspect of the programme to someone who was not part of the process. They were involved in identification of medicinal plants, collection, and discussion with agriculture and health experts, in the health camps, and of course in the physical creation of the BCRA.

The students’ creativity and joy was evident as they actively immersed themselves in planning and setting up Sanjeevani exhibitions, rallies, and village awareness campaigns. They created Sanjeevani slogans, games, seed bank, literature and clipping compilations. They learnt how to use the plants to treat simple ailments that were common in the hostel like cough, cold, fever, sore throat, boils, constipation, etc. When someone had a headache or a cut or wound, students would run to the medicinal garden and ask, “Sir, which plant shall we use?” We ourselves were amazed at how effective these were in most cases. By the end of the 3-year project, students had also passed on this experience to their families who also started using remedies such as decoction of ardusi for cough and colds, regular consumption of tulsi leaves, etc.

Students learnt to tackle challenges. Maintaining a garden in a water scarce area was one challenge. One plant was allotted to each student for watering. Students were advised to wash their hands and utensils (avoiding soap or other chemicals) near their plant. A drip irrigation system was installed with the help of experts. Also, during vacation when the hostellers went home, the nearby village children took up the responsibility to water the garden.

Before the project, most of us teachers were teaching forestry and medicinal plant chapters out of textbooks. But after the development of the BCRA, this became a nature laboratory and educational tool for teaching not just these topics, but also botany, nursery raising, mathematics, soil science and many more. The BCRA also became a lab for project work; to observe, experiment, and monitor various aspects of plant growth, understanding taxonomy, soil science, water conservation, and so on.

Initially, we were also a bit unsure about how we could handle the new responsibility, especially as we felt we did not have adequate knowledge or the experience in running such an activity based project. The experience and involvement in the project not only gave us the opportunity to learn a lot about biodiversity, it also gave us a new identity as resource persons within the teacher community. As facilitators we had to learn different aspects of project management, and the experience enabled a more professional approach to our work.

Through Sanjeevani we understood that learning is not confined to a classroom; indeed, true learning takes place when students feel one with the surroundings—social and natural. Similarly, students as well as teachers have also realized that a lot of knowledge lies with farmers and traditional healers, and have started respecting their wisdom.

Challenges, constraints and steps taken to overcome them

Through the project we could address many of the critical challenges secondary education faces today in developing countries, such as making education relevant, introducing students to ‘work life’, helping them to inculcate values, respecting traditions and cultures, respect for manual work, which helps them break class and caste barriers which are extremely sharp in Indian society, and most importantly integrating the concepts of stewardship, equality and sustainable development without any additional curricular burden.

How to make education a multi-way process in which all learn from each other was another challenge. In Sanjeevani, this was addressed through collective exposures, field visits and consultative meetings. Teachers and students together learnt from the barefoot scientists of the project – the traditional healers and farmers, while farmers learnt new and better farming techniques from schools and experts.

Making teachers accept that a lot of education, rather true education, happens when students are actually exposed to real life and livelihood issues was another challenge. Developing BCRA helped the teachers realize how this can be achieved and how it benefits students.

Introducing and adapting the participatory, bottom-up approach in a traditionally authoritative environment of rural schools itself was a challenge. This challenge was overcome by constantly discussing and consciously demonstrating the benefits of the process.

Ramesh Savalia is a Programme Coordinator at Rural Programmes Group, Centre for Environment Education, Ahmedabad.