The first time I was addressed with a specific name because of my skin colour was in the third standard. I remember it vividly; the name, the laughter that followed and that uncomfortable ‘sinking’ feeling that took over my 8 year-old self. “Come on, we’re just teasing you” said my friend who had proudly conferred that nickname on me. It all begins with the teasing, of course; innocent and playful. The nick-name stuck to me well into my adolescence and I gradually made peace with it.

As I grew older, there were many more instances that compelled me to feel that my skin colour is an ‘aberration’ (something unpleasant and almost a defect); the constant suggestions to try certain brands of fairness creams, to wear only certain colours (so that I don’t look darker) and avoiding playing in the sun lest I get more tanned! Now, for many of you reading this, it might sound very absurd but those ‘harmless’ (at times, well-intentioned) comments actually played a major role in how I perceived myself and my worth. Unfortunately, this is the lived experience of many girls (and also boys) who do not fit into the standard of beauty set by a society obsessed with white (fair) skin. It would not be an exaggeration to term this obsession as a subtle form of racism amidst our very own hierarchical society that practices multiple forms of domination-subordination, often unapologetically.

Colourism- an act of prejudice against people of a certain skin colour (mostly dark) usually within one’s own racial or ethnic group- is a major cultural problem in India. To put it more blatantly, skin colour has certain cultural meanings/values attached to it and people with darker skin tones are treated differently than the ones with a lighter one.

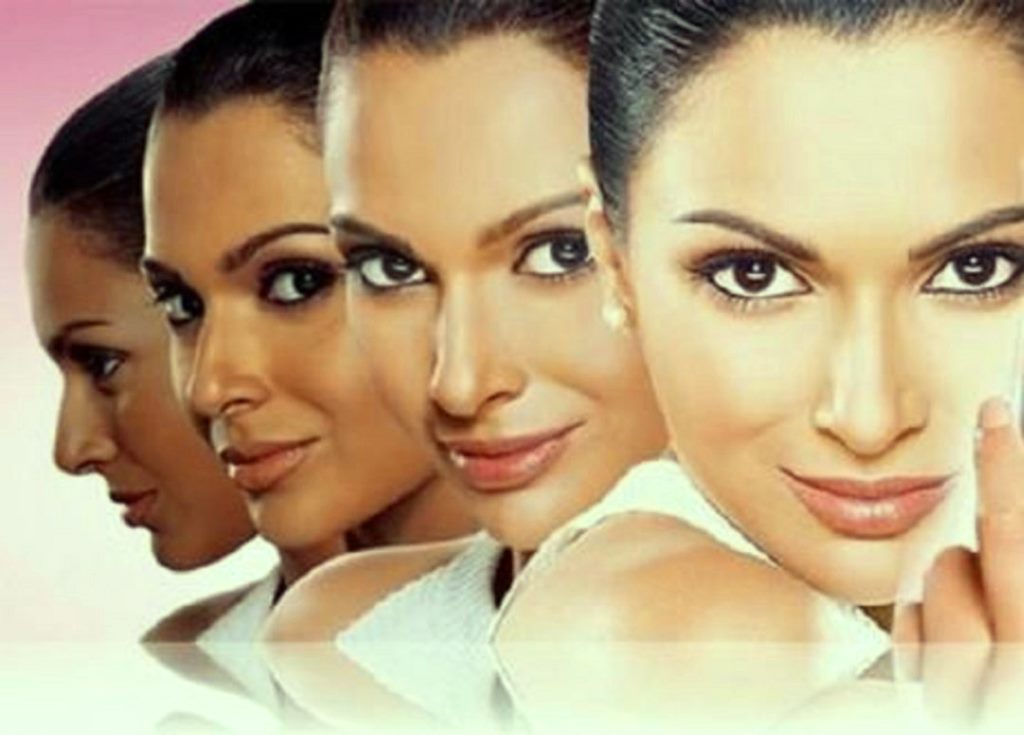

Fair skin is often considered desirable and is also associated with the standard definition of ‘beautiful’. Popular media- like films, advertisements, etc. – has played a staggering role in reinforcing this belief through multiple depictions of light-skinned women getting jobs easily, being readily accepted in the marriage market, succeeding in romantic relationships and radiating with ‘confidence’. Fair skin, after all, is a social capital.

In fact, the market of fairness and skin whitening creams has strived on a narrative of transformation- ‘dark and struggling’ to ‘fair and successful’. Of late, these depictions are not limited to only women though. Men, too, are being driven into this narrative with fairness creams designed ‘especially’ for men’s skin. What is absurd, however, is the expansion of this fairness obsession to certain areas of the body- like arm pits and the vaginal area- which are not even physiologically supposed to be ‘white and spotless’! Hard to believe, but truth of our times!

It is often wondered where the colourism in India roots from. Is it a hand-down from the colonial times when white-skinned Britishers held prejudiced opinions about the brown-skinned Indian slaves? (There are, indeed, accounts tracing how the British often displayed their colour bias by appointing Indians with a lighter skin tone to important administrative positions.)

Or is it a consequence of the post-British era when Indians (consciously or unconsciously) internalized the Britishers’ idea of white-skin being a symbol of superiority? Actually, the real reason is still not clear. The problem, however, lies in the fact that colourism is not even identified as a potent form of prejudice in the country. It has been ingrained in common perceptions and beliefs in a way that makes the white skin obsession (and hence the belief that- fairness/lighter skin means ‘beautiful’) seem like a norm.

The racist discrimination faced by the Blacks in the United States or that of the Jews in Nazi Germany have clear physical, cultural and historical denominations to be read and understood. But for a prejudice like colourism that is so subtle and often so easily incorporated in people’s day-to-day beliefs and practices, understanding it and, thereby, attempting to question it is really challenging. Some might say that colourism is not even a real prejudice since it involves no apparent ‘harm’. But as we know from our understanding of racism, violence need not necessarily be physical or even apparent to be identified as violence. The fact that bias based on skin-colour potentially causes distress (if not physical, at least psychological) is evident enough of how significant it is to educate ourselves about it.

Recently the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States sparked a world-wide debate on racism and its latent and manifest practices of prejudice against people of colour. The ripples of the movement reached India in the form of stern criticisms against fair-skin obsession. Fairness and skin whitening creams were criticised and popular Bollywood celebrities were called out for endorsing these products and supporting racism irresponsibly. In the wake of all these, the most popular skin lightening cream in India- Fair and Lovely (by Unilever) recently declared that it would drop the word ‘fair’ from its product’s name and also stop suggesting that fair-skin is the source of success/happiness in their advertisements. Indeed, a welcome move and a much appreciated gesture. But it is important to ask- is this gesture enough? Will the new promised narrative of being successful and desirable in society even with a dark skin-tone bring an end to the deep-rooted colourism that exists? Will this move really garner a sense of inclusiveness and sensitivity amongst people? I believe the answer is a hard no. The problem is not simply limited to the superficial level of product-advertising and consumption. Rather, the product-advertising mirrors values inherent in the psyche of Indian society. What needs to be understood is the fact that it is not simply about a preference for fair skin; the colourism that exists in our country expresses itself as acts of discriminating against and belittling the ones that do not have fair skin. The nuances are complex and very closely intertwined with every day actions that we carry out without giving much thought. Letting our friends, siblings or children assign skin colour-based nicknames to their classmates or colleagues, telling someone to ‘try’ a certain fairness cream because we think they’ll look better, overlooking skin-colour based jokes made by people around us and on popular media, and, most importantly, choosing to believe that all these are seemingly ‘harmless’ acts carried out in good humour actually feeds into the growth of a skin-colour based bias. The problem lies in front of our naked eyes yet we fail to see it.

An individual can be many things based on her/his intellect, creativity, hard work and potential. Only if we open our minds and learn how to simply look at each other as equal individuals and nothing else (like physical attributes, community, race, etc.), prejudices based on colour and maybe even caste, class and gender can someday die a natural death. Till then, small victories like seeing the word ‘lovely’ without necessarily being attached to the word ‘fair’ should keep us hopeful that the times indeed are changing.

Sabiha Mazid is a research scholar pursuing her Ph.D in Sociology at J.N.U.