VIEWPOINT

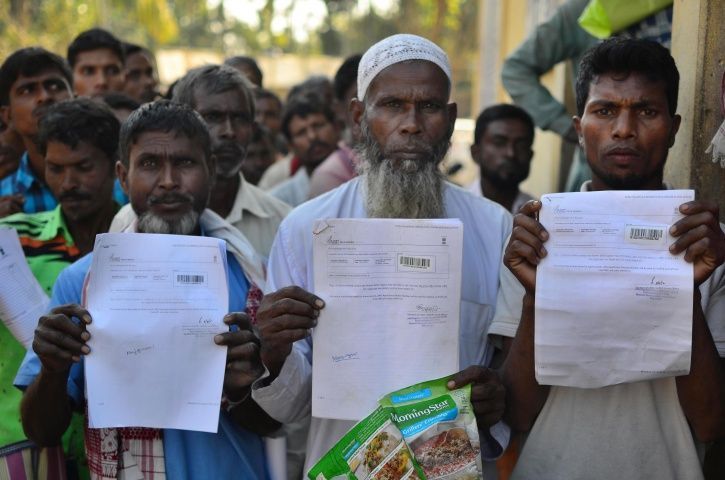

As more than 40 lacs citizens have been left out from the list and have been rendered stateless, the state of Assam faces a turbulent phase when notions of identity, statehood and political dynamics all come face to face posing several questions before the people.

What is the Turmoil About?

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he National Register of Citizens and the Citizenship Amendment Bill are two parallel processes that have created an atmosphere of utter confusion, suspicion and restlessness particularly for those who are suspected as illegal residents of Assam. By illegal resident in Assam, the general perception is that he or she is not an Indian citizen and that in all probabilities he or she has fled from Bangladesh. The NRC which is a document to update the list of Indian citizens primarily based on legacy data apart from other documents, to show the line of decent proving that the ancestors of the given individual have had been an Indian citizen.

In this context, the Assam Accord becomes crucial, signed between the Government of India and All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) ending a long drawn movement against the ‘foreigners’. This Accord led to an amendment in the Citizenship Act whereby it inserted an exception for Assam in the Act by setting the cut off date for Assam as March 24, 1971 instead of July 19, 1948 which is the cut off date for the rest of India for acquiring citizenship.

Socio-Cultural Roots of Assam and Troubled Bonds with India

In this regard, it is crucial to understand the socio-historical context of Assam and its relation to the Indian state to grasp the ground realities. Migration is not a new phenomenon in Assam. Rather, at different junctures of time, various communities have set their foot in this land and settled here. The Ahoms for instance who ruled Assam for around 500 years came from the northern and eastern hill tracts of Upper Burma and Western Yunnan.

However, as a part of invasion and accession strategies of dynasties, the Ahomes too extended their empire and made Assam their homeland. But at that time the western notion of nation state was not introduced which latter was going to be definitional for the identity of India. The arrival of colonial rulers led to the ‘we’ feeling which is essential for any community to turn into a nation-state. However, one should not mistake the creation of this sense of belongingness to be organic. Rather, it is a result of the European quest to familiarise themselves with what they regarded as the ‘other’ leading to the construction of the ‘orient’ based on certain investigative modalities like the census.

In such a background, at another level, a consolidation of regional identity was also taking place. The construction of Asamiya identity and Assam in general can be seen as the consequence of these notions of nation, state and the people.

Monirul Hussaien, one of the leading academicians of Assam writes that Asamiya means those people who have accepted Asamiya as their mother tongue while Assamese means all inhabitants of the state of Assam.

Today, the entire issue was more about this identity of who is an Asamiya and the protection of its authenticity than foreign nationals. At this point, it is crucial to understand that the nature of conflict is more about cultural than religious.

It is more about Culture and Less About Religions

As the Ahom rule got weakened due to internal contradictions, it paved the way for Burmese invasion and latter the arrival of British in Assam. The British in pretext of saving Assam from Burmese army conquered it making it a part of British India in 1826 thereby linking it with colonial capitalist world economy. However, the existing Ahom bureaucracy did not fit into the modern bureaucratic structure of the colonial rule.

The British colonizers also had no intention of educating the Asamiya immediately in order to ensure their continuity in the new colonial set up. This in turn delayed the process of formation of a western educated middle class among Asamiya. Therefore, it explains the import of ‘Baboos’ from neighbouring Bengal to recruit in the junior level positions of the colonial administraton in Assam. It is important to understand that the British colonised Bengal much earlier and a new middle class emerged with the expansion of western education in Bengal presidency from the Bengali Hindus mainly drawn from the upper castes .In the absence of an Asamiya middle class in the early colonial Assam, the Bengalis, largely Hindus monopolised nearly all jobs meant for the Indians in the colonial administration. This eventually led to their domination in all aspects, most visibly with the question of language. For their administrative convenience, the British authorities introduced Bengali in place of Assamese in the schools and courts of Assam. This replacement of language resulted in a sense of animosity between what latter would be defined as the two linguistic communities of Bengalis and Assamese.

Historicity and the Recent Impasse

This understanding of the historical context is important to locate the current impasse in the state. Though the debates around NRC and Citizenship Bill have been more about the illegal migrants specifically from Bangladesh, one cannot have unilateral approach towards the whole issue. We have to understand that the entire issue of Asamiya identity and its relation to safeguard it from monopolization of the ‘outsiders’ stems from the political economy which the British constructed for the continuation of their reign. For instance,since Assam was thinly populated during 19th century ,therefore, the British had to directly or indirectly patronised migration of peasants from thickly populated East Bengal to Assam’s waste land. This was all to generate more land revenues and profit the ‘crown’.

Besides, the post-independence period also witnessed neo-colonial hegemony in the form of Indian state. Despite being abundant of resources Assam’s economy continued to be stagnant. It is because Assam was denied the share of what it produced. For instance, many of the tea estates were transferred to big industrialists and as result of concealment of real profits, Assam who was entitled to get 60% of the profit had been deprived of it. Therefore, the unwillingness to attend to and the failure of political leadership of post colonial India in developing the economy and infrastructure of Assam caused anguish amongst the masses which accumulated and burst out in the form of Assam Movement. The movement though was for the detection and deportation of the illegal migrants but the larger context of Assam being ignorant within the Indian state is significant to take into cognizance.

In this regard, when today we look at the uncertainty and volatile situation prevailing in Assam, we can see two strands of arguments. One is against the ‘Bangladeshi illegal migrants ‘and other is against ‘all the Bangladeshi illegal migrants’ irrespective of religion. This is what been said by Robin Bora from Kamrup district who works as daily wage labourer. He says ‘We are very poor people but one thing that we know is , we do not want our work to be taken away by outsiders irrespective of any religion.’ He further says that if one knows that he or she is citizen of the country then why is there any reason to fear. He did not fear even though the process of enlisting one’s name in NRC was very tiresome and precarious.

Grassroot Voices

Bubul Deka who works as a peon in the District collector’s office and hails from North Lakhimpur district says, “I am glad that the process of NRC has been completed. No Assamese should now fear from ‘Bangladeshis’ that they will one day dominate over us in our land.’ Whether Hindu or Muslim, he says that a foreigner is only a foreigner and that his religion and language do not matter.”

Across Assam, there is a clarity that a communal colour that the amendment to the Citizenship Bill seeks to bring will be very dangerous and fail the very purpose of the struggle of thousands of Asamiya to protect their land. It is very interesting that how our identities are not singular but has layers into them. Similarly, Asamiya identity has many layers and gets entwined with class, ethnicity, caste and gender. Therefore, the question remains that whether the reiteration of this Asamiya identity is an inclusive one or does it echoes a dominant notion of Asamiya identity representing the Assamese ruling class.

However, on other hand,there is also suspicion and anxiety particularly among certain sections of Muslims and Bengalis. Rahima Khatoon, who works as a maid and is from Dhubri district, says that although her forefathers fled from Bangladesh but she is an Indian citizen. Her name appears on the NRC list and thus,she is relieved that no one will look at her with suspicion. She says that she earns her livelihood from this land and that besides Assam she has nowhere to go.

Sudipto Das, who hails from Karimganj and is a Bengali by birth says that the rift between the two communities is not new. But, since after the Assam Movement, there has not been any major tension with regard to cultural differences. He further says that he is bilingual and that he is both an Assamese and a Bengali. However, lately, the situation has become very sensitive specifically because of gross politicisation of the entire issue by different political parties. This needs to be stopped immediately to preserve the harmony of the state.

In this scenario, one can understand that people living in Assam, who are the primary stakeholders of this entire process have been somewhat obscured from the ‘public opinion’. This reminds us of what Jurgen Habermas, a German sociologist had said about the hijacking of the ‘system’ by some ‘experts’.

[irp]

Assam has become a pawn in the hands of the political parties to meet their own interests and to increase their probability of winning the great battle of 2019. What is being forgotten is the fate of those whose names have not appeared in the list even though the process of inclusion of names is not over. Being a democratically vibrant country, the question arises that can we afford to render so many people stateless. In this context, another question that emerges is why till date there has not been any diplomatic as well as political discussion with the Bangladesh government on this matter. NRC might rightfully detect the illegal migrants but then what about their deportation which was also one of the demands of Assam Accord. Amidst these questions and complexities, when the Citizenship Bill proposes changes in terms of religious biasness, it naturally leads to reactionary response. At this moment, only a true spirit of political leadership and matured politics, a responsible and grounded civil society along with a public calmness and their equal participation can see a possibility of resolving the issue.