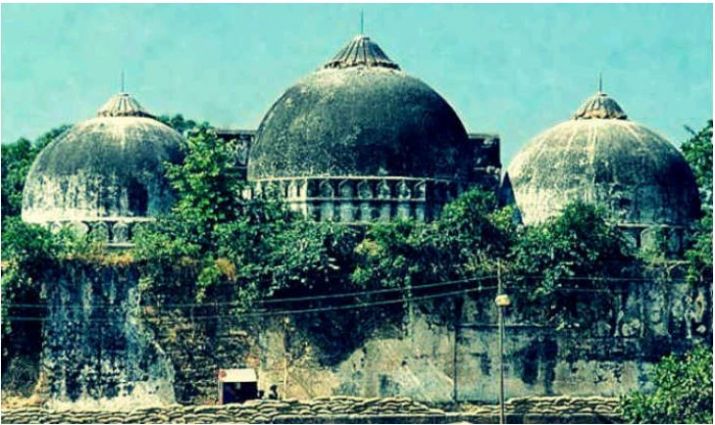

I was born in the year 1992. My grandmother used to say that I was born in the same year when Babri Masjid was demolished, and the curfew was imposed in our city. This practice of remembering the birthday in terms of some extremely important event that defined that ‘time’ was a common practice in traditional societies. The significance of Babri Masjid demolition for people who were located so far away from Ayodhya, where the mosque was demolished by a Hindu mob, informs us about the importance of this event in our nation’s history. The act of demolition of a 16thcentury mosque by a violent Hindu mob led by Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) on 6th December 1992 was a significant rupture in the post-colonial polity of our country. This demolition also symbolized the demolition of trust in secular foundations of our country, which was reposed by the citizens of this country after the bloodletting of partition. The Muslims who stayed back in India even after the creation of Pakistan expressed their trust in the secular foundation of our republic and legitimized its commitment to secularism by deciding to stay in India in the extremely fragile and violent times that defined partition. The demolition of Babri Masjid irreparably damaged the trust in the Indian secularism. The violent demolition exposed the flimsy commitment to secularism that the Indian state and society promised to uphold when the Indian nation came into existence.

The long court battle for the title suit of the disputed land that ensued after the demolition of Babri Masjid came to its culmination on 9th November with the supreme court judgement accepting the claims and demands of the Hindu Party and granting them the possession of the disputed site ( which is considered to be the birthplace of Lord Rama) and ordered the government to provide 5 acres of land to the Muslim party in a prominent place in the city as some sort of a compensation. This verdict of the supreme court has accepted all the major claims of the Hindu party and left the Muslim party ‘unsatisfied’ to use a euphemism. I personally have serious reservations about the verdict; however, my major concern is the public reception and perception of this verdict of the highest court.

We are now standing at a crossroads when the majoritarian nationalism is crushing the idea of inclusive nationalism. We have to choose if we want to reclaim the idea of the nation based on equality, liberty, justice, and freedom, or we want to walk down the cesspit of majoritarianism proudly.

Social media was overflooded with posts about maintaining peace and respecting the supreme court verdict when the news about the date of the verdict was announced. It seemed like everyone had a premonition about the verdict. Our prime minister going out of his way, tweeted several times the night before the verdict-day to exhort citizens to maintain peace and not to indulge in provocations. The great leader is known to maintain threatening silence when incidents of brutal mob lynching and riots take place in our country; however, he was overwhelmingly vocal about the maintenance of peace this time. I wondered towards whom these exhortations and uproar for peace was directed. The verdict upheld all the claims of one group, and hence they would have no cause for resentment and protest. The other group who was brutalized by the mosque demolition in 1992 and the court denied them possession of the disputed land in its verdict would be feeling a severe sense of pain and angst against the verdict. A certain sense of exuberance could be felt in the clamour for peace, which was matched by the deafening silence from the other side. The defining aspect of majoritarianism is not the violence that is perpetuated by the majority against the minority but the denial of the right to resent and protest against the violence. The ‘peace’ post-verdict doesn’t appear peaceful. The republic seems to mourn its own brutalization in the name of peace in the silence, which marks the aftermath of the verdict.

The Babri Masjid demolition was the most significant rupture in the Indian post-colonial history. It announced the mainstreaming of majoritarian nationalism, which would change the secular face of the republic in the times to come. The ransacking of the mosque and the government’s inability to protect it lay bare the myth of secularism that the republic wore as a cloak. It created a seemingly unbridgeable gap between the Hindus and Muslims. The post-Babri India was different, much more divided and violent. It was an affront to the idea of India which believed that a strong and vibrant nation could be forged by respecting human multiplicity. The tombstone of the inclusive idea of India was created when Babri Masjid was demolished. The majoritarian nationalists since then regularly propitiate the tombstone of the secular republic in Ayodhya.

We as a nation have slid down the slippery slope of majoritarian nationalism since 1992 and have been actively destroying the remnants of promissory note that promised an inclusive nation after independence from the colonial powers. At the very onset, this promise faced an intractable obstacle with the partition and the communal bloodbath that defined the holocaust of partition. Millions of people migrated from one side of the border to another amidst the most gruesome violence one could ever imagine. Millions of Muslims stayed back in India to become a part of the most diverse nation ever forged in the human history. The secular foundation of this nation promised a future of peaceful coexistence of a multiplicity of human faiths and cultures. Someone who thoroughly embodied this promise was a person called Abdul Hayee, who was popularly known as Sahir Ludhianvi. When Muslims were fleeing to Pakistan after the Partition, he made an opposite journey from Pakistan to India in 1949. He wrote later, “Tu Hindu Banega na Musalman Banega, Tu Insaan ki Aulaad hai Insaan Banega.” This is how millions of Sahir’s reposed their faith in the Indian secularism by upholding the idea of India and by just being present in it. We are now standing at a crossroads when the majoritarian nationalism is crushing the idea of inclusive nationalism. We have to choose if we want to reclaim the idea of the nation based on equality, liberty, justice, and freedom, or we want to walk down the cesspit of majoritarianism proudly. The ‘silence’ of the citizens would mean acquiescence to the majoritarian forces.

Kunal Shahdeo is pursing his Ph.D at IIT, Mumbai .