Friends, we are gathered here to remember one of India’s great freedom fighters, Bhagat Singh. But before I start to talk about Bhagat Singh, I want to remember two other great Indians. The first is a great Indian who is still very much with us, Sudha Bharadwaj. Sudha Bharadwaj is an IIT Kanpur graduate and has spent the last thirty years of her life working as a lawyer who defends the rights of workers and farmers. Sudha Bharadwaj was the speaker last year in this same memorial talk on Bhagat Singh. A couple of months after her talk here she was arrested in Delhi. She is presently in jail in Pune on charges of being a Maoist terrorist. Having heard her talk last year, like many others in this country, I too, find this charge very difficult to believe. My sincere hope is that that our legal system will sift the truth from falsehood.

The second great Indian we should remember before we talk about Bhagat Singh is B.R. Ambedkar. B.R. Ambedkar was arguably one of the greatest intellectuals of the first half of the twentieth century and it is worth remembering him because he warns us against hero worship. This is an important precaution to take when we talk about Bhagat Singh. Bhagat Singh himself was against hero worship and refused to idolize Gandhi, Nehru, Tilak and any of the other great leaders of that time. Ambedkar warns us in a very beautiful way of the dangers of hero-worship:

Hero-worship in the sense of expressing our unbounded admiration is one thing. To obey the hero is a totally different kind of hero-worship. There is nothing wrong in the former while the latter is no doubt a most pernicious thing… The former does not take away one’s intelligence to think and independence to act. The latter makes one a perfect fool.

– Ambedkar, B. R. (1989).

We will look at Bhagat Singh not as an act of hero-worship, but as Ambedkar puts it, in search of all that is noble in humanity. We shall admire what seems noble and stay away from what is not.

Bhagat Singh was born in 1907 at Lyallpur district of Punjab, which is now known as Faisalabad in Pakistan. We all know the story of Bhagat Singh. Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and many of their comrades had plotted to avenge the death of Lala Lajpat Rai. Lala Lajpat Rai had been hurt in a lathi charge ordered by the Superintendent of Police Jock Scott on 30th October 1928. Lala Lajpat Rai had then died of a heart attack on 17th November 1928. Bhagat Singh and the others believed this to be the result of the lathi charge. Exactly one month later, Bhagat Singh and Shivaram Hari Rajguru attacked a man who they had been told by one of their comrades was SP Jock Scott. But that was a mistake and they instead killed the Assistant Superintendent of Police John Poyantz Saunders (age 22) on 17th December 1928. Saunders had been in India for less than a year at the time of his death. Chandrashekhar Azad is believed to have killed Saunder’s Sikh munshi Chanan Singh who tried to chase them. While this murder was planned with the intention of rousing the masses to protest against the British, that intention seems at that time to have failed. The attendance at the Naujawan Bharat Sabha actually fell. It was much later, when in jail, that Bhagat Singh began to capture the imagination of the country, particularly its northern parts.

Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt on 8th April 1929 threw two small bomb into the Legislative Assembly at Delhi. This was deliberately done to provoke popular sentiment and rouse the masses into protesting against colonial rule. There was some discussion amongst the conspirators as to who should go for this and there was concern that the police might identify Bhagat Singh as one of the people involved in the killing of Saunders and Chanan Singh. But Bhagat Singh was by far the most articulate and outspoken of them. He insisted that if the trial was to be made the site of public mobilization, he was the best person to do it.

He was hung to death by the British colonial rulers on 23rd of March 1931. His death was designed by him to be a statement of protest and a means of rousing the people of India. In his last letter to the governor of India, in words dripping with sarcasm and irony, he and Sukh Dev and Rajguru demanded that they be shot and not hung.

“As to the question of our fates, please allow us to say that when you have decided to put us to death, you will certainly do it. You have got the power in your hands and the power is the greatest justification in this world. We know that the maxim “Might is right” serves as your guiding motto. The whole of our trial was just a proof of that.

What we wanted to point out was that according to the verdict of your court we had waged war and were therefore war prisoners. And we claim to be treated as such, i.e., we claim to be shot dead instead of to be hanged. It rests with you to prove that you really meant what your court has said.

We request and hope that you will very kindly order the military department to send its detachment to perform our execution.”

Yours, etc.

Bhagat Singh, Raj Guru, Sukhdev

The education of Bhagat Singh

I am struck by the audacity of the letter. He was due to die in another month or so and there he was, still cocking a snook at the British. What created such a person?

Bhagat Singh came from a family of political activists. His father Kishan Singh had been involved in supporting revolutionary organizations and engaged in various social reformist activities. His uncle Ajit Singh had been part of more aggressive and fiery actions and had been sent off to jail in Mandalay along with Lala Lajpat Rai in 1907. This uncle had been part of public campaigns of mobilizations of farmers and protests against British laws. He was eventually banished from the country altogether. So part of what shaped Bhagat Singh was the inspiration and role models which a family like this must have provided him.

The college Bhagat Singh attended was also quite unusual and must have contributed a great deal to making such a man. Hailing originally from a rural family, he was sent to study in Lahore, the great bustling metropolis of the Punjab of that time. At that time what we today consider 11th and 12th grade were also done in a college. He spent a year at the DAV College and then switched to a very remarkable institution. Bhagat Singh studied for a while at the “Punjab Qaumi Vidyapith” or the National College at Lahore. This was part of a series of national colleges set up as part of the freedom struggle inviting people to leave British sponsored education. Gandhi and other national leaders had declared that the conventional kind of British education only sucked people into the labyrinths of power. They set up a number of national institutions as an alternative for young people and academics, including places like Jamia Millia, Kashi Vidyapith and the Punjab Qaumi Vidyapith. The Lahore National College was an institution which was strongly influenced by Arya Samajis like Bhai Parmanand and Lala Lajpat Rai. Here Bhagat Singh was also inspired by teachers like Jai Chandra Vidyalankar who told him about the Russian revolution and the success of the war against the Czar. Students also learnt about European revolutionaries like Garibaldi and Mazzini. They learnt about the Irish Sinn Fein and its ultimately victorious struggle for freedom from the English. All this was deeply inspiring.

We are often told about the infrastructure of educational institutions. This remarkable college had almost nothing. They did not even have a library. The teachers would ask students to read materials from books that they borrowed from public libraries. What is most important for an educational institutions is the quality of teachers and this the Punjab Qaumi Vidyapith did not lack. The teachers were intellectuals of stature and built a very friendly and interactive relation with the students. Bhagat Singh’s principal Chhabil Das (Bakshi 1988: 22-23) has written about the warm bond he had with his students. They would spend moonlit nights by the river, talking about many things. When Chhabil Das was to get married, Bhagat Singh turned up to remonstrate before him, saying that marriage would prevent him from doing important things. Chhabil Das patiently replied that having a wife who thought for herself and shared his political and cultural interests would actually enable him to achieve much more. He gave the example of Mrs Sun Yat-Sen and the wives of other world leaders. Bhagat Singh was quiet for a while and then said “Guruji, who can vanquish you in argument.” It is such a learning environment that encouraged learning and debate that produced a mind like that of Bhagat Singh. It was possible for a 15-16 year old student to come up to his principal and try to persuade him not to get married. And it was possible for the principal to respond with sincerity and logic. The culture of the nation which was being built here was one of courageous questioning and of reasoning. It was not one of blind obedience.

We hear again and again of Bhagat Singh’s being a voracious reader. People tell of meeting him and finding his kurta pockets bulging with books. One of his last letters from his death cell is to a friend asking him to go to the public library and issue five books and send them with a visitor coming to see him. The quality of his mind comes through in an introduction he wrote two months before his execution for Lala Ram Saran Das’ book The Dreamland. I have never read an introduction like that. He interrogates the contents of the book and on certain points says that if the author had in mind a certain thing while writing his lines then he was with him, but if not then their positions were different. Towards the end of the introduction he says:

I strongly recommend this book to young men in particular, but with a warning. Please do not read it to follow blindly and take for granted what is written in it. Read it, criticize it, think over it, try to formulate your own ideas with its help.

His classmate Jai Dev Gupta has written that Bhagat Singh left Lahore in 1923 and went out of contact with his family at least partially to get away from pressure from them to get married. He seems to have also already made up his mind that his would be a life of dedicated struggle. He moved to Kanpur which was then an important centre of revolutionary activities and became part of a group around the Congress-supporter journalist Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi. When they met, Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi asked him if he was prepared to endure all hardships and even lay down his life in the service of the country. Vidyarthi himself did exactly that in 1931 when there were riots in Kanpur and he plunged into them to rescue innocent Hindus and Muslim. Vidyarthi is said to have been responsible for rescuing thousands of people, both Hindu and Muslim, before he himself was done to death by the mob. To such a man Bhagat Singh said yes, he was prepared. He was 17 years old.

He began to work in Vidyarthi’s Pratap Press and became part of a vibrant group of young men who included Chandrashekhar Azar, Batukeshwar Dutt and many others. He was then made the headmaster of a a National School set up near Aligarh. Meanwhile his family had been looking for him and they pleaded with him through the poet Hasrat Mohani (composer of “Chupke chupke raat din aansu bahana yaad hai”) to come back for the sake of his ailing grand mother. He agreed to return and then onwards began to write for various magazines in Lahore and elsewhere run by like-minded people. He wrote wrote prolifically and Professor Chaman Lal and Professor S. Irfan Habib are still reporting fresh discoveries of letters and documents written by him.

From Kanpur onwards he often took up the name of Balwant Singh as a way of escaping recognition. It is in Kanpur that he became a member of the Hindustan Republican Association. In 1926 he was back in Lahore and with this experience of Kanpur behind him he founded there the Naujawan Bharat Sabha.

We can see in the growth of the young Bhagat Singh that people do not become completely dedicated to a cause all by themselves. This change takes place in them through the existence of institutions and cultures which thousands of others have contributed to. We may not ourselves be Bhagat Singhs. But when we live lives of honesty, courage and integrity, we contribute to that culture which produces Bhagat Singhs.

The political ideals of Bhagat Singh

By the time Bhagat Singh was 21-22 years old his political ideals have become those of social equality and of struggling to create an egalitarian society. He talks and writes of creating a society where there are no rich and no poor. He believes that the revolutionary forces in society rest in farmers and workers. It is by winning their support that this society can be changed. He knows very well that this is not an easy thing to achieve. He is now beginning to talk of a “utopian non-violence.” For some things he agrees non-violence is the best way to go. But if you have to overthrow deeply entrenched systems of exploitation, he believes that violence must inevitably be used.

Culture of Violence and Sacrifice

It is difficult in today’s times to grasp how a young man can become committed to a path that he knows very well will lead to death. Bhagat Singh was not arrested by accident. It was part of his design, just as his using the courtroom for the maximum publicity for his cause was part of his design. He also told his friends later that he would be achieving much by his death than by his remaining alive. In today’s times where the life of a young man is about consumerism, good salaries, mobile phones and aspiring to consume more and and more sensational items, we struggle to understand such an orientation.

The culture of sacrifice and discipline was very much in his family and in his education at the Punjabi Qaumi Vidyapith. Bhagat Singh in the trajectory of his life in Kanpur was plunged into a culture that explicitly promoted violence as a political strategy. The Hindustan Republican Association and its leader Sachin Sanyal had an underground wing which actively cultivated the cult of violent revolution. Sachin Sanyal in 1925 seems to be the author of a pamphlet written on behalf of the Hindustan Republican Association, which supports anarcho-terrorism, violence as a way of shattering all systems of oppression. Anarcho-terrorism was a political ideology that had gained popularity at the turn of the century in Europe and America. The basic idea was that a dramatic act of violence was necessary to break the passivity of the masses. This, they thought, would unnerve oppressors and unite the people. The theory of anarcho-terrorism was actively adopted by the Hindustan Republican Association and seems to have guided both the murder of Saunders and the later bombing of the National Legislative Assembly which led to Bhagat Singh’s arrest and hanging.

We can see a shift in how he looks at politics and violence over the span of his life. In the early years of his writing there is the passion and poetry of sacrifice and courage. But there is rather little of a larger strategy or plan for the future. Here is an extract from an article he wrote at the age of nineteen in the Pratap extolling the Babbar Akalis. He is seeing in his mind a scene where some radicals were surrounded by the police and describing it:

“We will sacrifice our all in the service of the country. We swear to die fighting but not go to prison.

What a beautiful sanctified scene it must have been, when the people who had given up all their family affections, were taking such an oath! What is the end of sacrifice? Where is the limit to courage and fearlessness? Where does the extremity of idealism reside?”

In his later writings we begin to see a much more mature approach. In his writings from jail he keeps insisting that he does not believe in the cult of violence, in bombs and pistols for their own sake. Instead now he is writing of concrete social goals. He is talking of exploitation and the desire to overcome oppression.

He writes a message for young political workers where he says that this is not the right time to take to guns. Instead he advises them to build a youth movement and then through that a revolutionary party. He says that compromises should be struck and they are not something to be shunned. Instead he says, giving examples of revolutionary movements from around the world, it is through compromises that gradually the movements begin to gain momentum. He uses the metaphor of asking for sixteen annas (at that time sixteen annas made a rupee) and getting one. He says that we should put the anna into our pocket and then move on to ask for more. The moderates instead make the mistake of asking for only one anna and then are unable to get even that.

By now Bhagat Singh has a different outlook on the use of violence. He says that the primary thing to do is to build the political party. The military wing is only secondary to that.

“Let me announced with all the strength at my command, that I am not a terrorist and I never was, expected perhaps in the beginning of my revolutionary career. And I am convinced that we cannot gain anything through those methods … If anybody has misunderstood me, let him amend his ideas. I do not mean that bombs and pistols are useless, rather the contrary. But I mean to say that mere bomb-throwing is not only useless but sometimes harmful. The military department of the party should always keep ready all the war-material it can command for any emergency. It should back the political work of the party. It cannot and should not work independently.“

The national imagination of Bhagat Singh

So what kind of nationalism does Bhagat Singh practice? It is important to remember that nationalism is a culture – it is a mix of values, attitudes and beliefs. There can be different cultures of nationalism. What Bhagat Singh’s nationalism is about is a deep commitment to the poor and a struggle to overthrow exploitation. Bhagat Singh’s nationalism is about reading and thinking. To serve the nation is to build organizations that will overthrow a society where some people keep the rest under their thumb.

Compare this with other kinds of nationalism. There is a nationalism which says that I love my country but I will not do anything for it. It says all I will do is to build my career while I praise others’ activities from a distance. That is not Bhagat Singh’s nationalism. He plunges in to work for the nation himself. There is another kind of nationalism which says I worship my country, my country was great in the past and is great even now, I will hear nothing against my country. That too is not Bhagat Singh’s nationalism. He is the first to criticize the social evils of his country. For him patriotism is not to close his eyes to those evils, but is to try and erase them. For this he is also open to learning from other lands. There is another kind of nationalism which says religion is the basis of the identity of the country. He reject this too. For him all religions are part of the nation. And more so, the long term struggle for freedom is the struggle to escape from an emotional dependence upon religion altogether. Bhagat Singh’s nationalism is the struggle to create a society where there is no rich or poor, where people think with courage and clarity, where there is no oppression of the mind or the body. His nationalism is about building a culture of courage and clear thinking.

Criticism and Appraisal

Before we turn to the educational implications of the thought and life of Bhagat Singh, it is good to ask if there are any problems in them. There are many things which are wonderful in the young Bhagat Singh, a person who died at the young age of 23. And yet we must not hero-worship him. We must not become bhaktas who see nothing problematic in his ideas. There are many problems, for he is after all a person of his times. Today we see that his analysis of social inequality was basically the Marxist analysis of his times. The weaknesses of his work includes his simplistic analysis of social classes and their revolutionary potential. The role of caste is very weak in his framework of thought. Patriarchy is almost completely absent. His theory of the state is the classical Marxist position that the state is the puppet of the capitalist class. Today we do not think in such a simplistic way. And yet there is much that is wonderful in his work and in his ideas. Those are the ideas that we can pick up and keep. With this precaution in mind, let us turn to what we can learn from him that is of relevance to education in today’s India.

Educational agendas

There are several implications of Bhagat Singh’s ideas for today’s education. The first thing to draw from him comes from his “Introduction” to Lala Ram Saran Das’ book “Dreamland” where he warns us that the attempt to create a better education in India must simultaneously be a political struggle. He agrees that a new world, one of equality and justice can be created only by education. But how can you create such an education system. The world’s systems of oppression and exploitation do not permit such a culture or education to emerge. They must first be politically (which includes militarily) opposed. Only then will it become possible to create an education that will enlighten and open up people’s minds.

A second thing to draw from him is that education should be about getting freedom from oppression. It should teach clear thinking and courage. It should aim at freeing people from the shackles of exploitation and stifling ways of thought. In a word, it should be an emancipatory education. We see here Bhagat Singh is standing in the same tradition as Paulo Freire and Jotiba Phule, he is asking for what we today call a critical pedagogy.

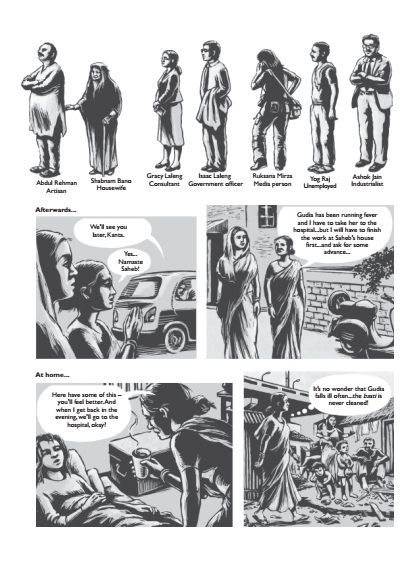

However this is only rarely to be seen in school curricula and pedagogic practices nowadays. Let me illustrate some of the good and the not so good in social studies textbooks. When we look at them we look not at whether there is a photograph of Bhagat Singh or not. Instead we look at whether there is an emphasis on emancipation, upon freeing the mind and overcoming social inequalities. Perhaps the textbooks which come closest to Bhagat Singh’s nationalism are those of the post-NCF 2005 NCERT and those developed by Eklavya and the Chhattisgarh and Kerala governments. To take the example of NCERT’s grade 8 Social and Political Life, here is a chapter on equality which is of great relevance today when we are about to go into elections for the national Parliament. This is a chapter which celebrates that we all stand as equals in the line to cast our vote. But it is also draws children’s attention to the fact that outside that we face great inequalities. The lady in the illustrations has a sick child but has no option but to wait till evening when she returns from work to take the child to see the doctor. The causes of the sickness are evident to her – they are unhygienic living conditions in her slum. And yet there is helplessness, because she cannot imagine what she can possibly do to fix that. Here in this textbook we see a vision which is in resonance with Bhagat Singh. Which draws our attention to the inequalities of our society and asks us in an urgent tone what we can do about them.

It is important to note that the NCERT’s textbooks don’t actually talk about Bhagat Singh up to grade 10. You don’t need to talk about him to share his values. And yet we find many examples of schools doing a song and dance about Bhagat Singh, but not understanding what he was doing at all. Here is another clip from a state textbook which does talk about Bhagat Singh but is so pedantic in its narrative that the child will not understand at all what Bhagat Singh lived – and died – for. Bhagat Singh’s ideology is spelt out in a terse, precise language. But that is of little use since the larger content and pedagogy is actually the reverse.

What I regret about the songs that we sing and ways in which we remember him is that all we hold dear are his violence and his early cult of sacrifice. What we forget are his rationalism, his commitment to social equality, the expanse of his knowledge.

What I regret about the songs that we sing and ways in which we remember him is that all we hold dear are his violence and his early cult of sacrifice. What we forget are his rationalism, his commitment to social equality, the expanse of his knowledge.

When we look at what this country has remembered of Bhagat Singh and what he actually meant, one recalls a sher of Ghalib which is said to have been a favourite of Bhagat Singh’s:

या रब वो न समझे हैं न समझेंगे मेरी बात

दे और दिल उनको जो न दे मुझको ज़ुबाँ और

Oh God, they do not understand and cannot understand what I say

Give them a bigger heart, if you do not give me a clearer tongue.

REFERENCES

Ambedkar, B. R. (1989). Ranade, Gandhi and Jinnah. In V. Moon (Ed.), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches (Vol. 1, pp. 211–240). Mumbai: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra. (Original work published 1943)

Bakshi, S.R. 1988. Revolutionaries and the British Raj. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers and Distributors.

Amman Madan is Professor at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru.