After “Indomitable Draupadi”, Sanjukta Dasgupta’s “Ekalavya Speaks” is another remarkable collection of poems justifying the poet’s use of language as a means of creative expression. Dasgupta’s collection of poems cover a wide range of issues- both thought provoking and brain storming. Her previously published collections – “Snapshots”, “Dilemma”, “More Light”, “First Language”, “Lakshmi Unbound”, “Sita’s Sisters”, “Unbound” and “Indomitable Draupadi” have raised certain questions which provoke the readers not only to think but also to learn how to feminize the art of humanity. Though titled after the epic figure Ekalavya, the collection has a diverse range of subjects. Dasgupta’s literary activism truly justifies Pamuk’s words. It is true in every sense that her creative writing is synonymous with literary activism. Caste and gender discrimination intersect and this is how Dasgupta’s pen becomes mightier than the sword. The poet catches Ekalavya, the tribal prince at the quintessential moment of his life. Dasgupta tries to venture into the torn psyche of Ekalavya who is dismissed and abandoned for his subaltern status. Some of the poems in this collection are based on marginalized epic characters as Ekalavya, Shambuka, Karna, Shikhandi. A close reading of such poems justifies how Dasgupta’s words empower the disenfranchised male epic figures and queer identities. She provides them a platform to speak, as the gendered subalterns speak. Feminism combats against the system of inequality and patriarchy; not against men and others. As Draupadis and Sitas; Karnas, Shikhandis and Ekalavyas also find space in her poems.

Dasgupta’s dream of a classless society is prominent in poems like ‘Hate Unleashed’, ‘Classless’. ‘Borders’, ‘Manipur’ talk of the relentless threat on humanity and the poet’s deep concern over this issue. Her craftsmanship is tantalizingly beautiful through the use of words, rhymes and the rhythmic effects they produce – “Bubble Bubble Trolling Trouble/Gloom and Doom sneer and chuckle” (Borders).

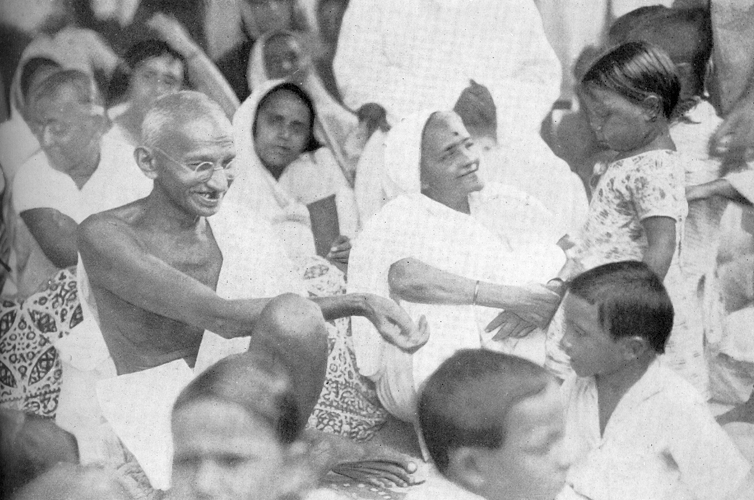

While poems like ‘Bapu’ and ‘Chuni Kotal’ expose the tyranny, hypocrisy, violence, shallow arbitrariness of the society towards women; ‘Hunger in the Metropolis’ reminds the readers of Bijon Bhattacharya’s remarkable work “Nabanna”. In “Nabanna” human beings and dogs fight for the same source of leftover food. In Dasgupta’s poem “The stray child and the stray dog/Sat side by side on the footpath/ Staring unblinkingly at the shelves/Full of enchanting food that they/Would never taste.” (‘Hunger in the Metropolis’) It is visually disturbing but it is the hardcore reality.

Dasgupta’s angst against the petty tyrannies of religion and politics is not hidden. She stamps her protest against ‘carnivores’ and ‘cannibals’ who are in the endless process of making heaven hell and vice versa. She shows the incessant bleedings of heart as it riddles with “bullets/ Spears and arrows are lodged”. ‘Religion and Politics: A Dialogue’ is the poet’s clarion call to come up with resistance- not to endure pain and suffering, not to take insult anymore. ‘The Reluctant Voter’ is a trigger warning for any upcoming election which perpetuates violence, life risk, threats in the name of democracy. Rather it is the biggest defeat of democracy Dasgupta attempts to focus on. ‘Amphan Super-Cyclone 2020’ and ‘The Curse of Joshimath’ express the poet’s concern for humanity, her empathy towards fellow human beings and her despair against the callousness of the same humans who are responsible for such disasters.

An intense reading of ‘International Women’s Day’ would naturally convince the reader that instead of considering this day for ‘…hair colouring/ Facials, manicure, pedicure and tweezing’ one could think of women’s role in a more productive sense. Women are not mere objects- that is how the society considers her to be. Dasgupta asserts that such attitudes must be changed. A woman is not merely ‘A mannequin manipulated/ In sequins and beads’, she can head the team of a scientist, become the president of a country and play multifaceted roles to change the course of a nation as well. ‘Indian Woman at Home and In the World’ situates women at the crossroads, expressing her claustrophobia against the age old traditions and how she is a victim to be a ‘good Indian woman’ who prays ‘all the time’, ‘pray in silence’, ‘pray for freedom’, ‘pray for confidence’, an Indian woman who is ‘alert 24×7’. ‘Husband Ji’ harps on the patriarchal role a man. ‘Good wives do not reply/Good wives do not reason why/Good wives just do and die’ questions the stereotypical role of a woman fixed by the patriarchal society. ‘Patriarchy triumphs like a gas baloon’ simultaneously evokes humour, pathos and the satiric undertone. Such expressions prominently justify Dasgupta’s role as a poet. It could remind us of Adrienne Rich’s words on the role of a poet: “We may feel bitterly how little our poems can do in the face of seemingly out-of-control technological power and seemingly limitless corporate greed, yet it has always been true that poetry can break isolation, show us to ourselves when we are outlawed or made invisible remind us of beauty where no beauty seems possible…” (Rich, Essays and Letters) Dasgupta’s poems provide the readers such soothing comfort- it isolates the readers from the deep pessimism and enables them to fight for truth, peace and security.

‘Goodbye Mallika’ is Dasgupta’s tribute to the famous poet Mallika Sengupta who left for heavenly abode at quite young age. Dasgupta translated Mallika’s poems in English. Unlike Mallika, for Dasgupta, ‘feminism is not just an academic issue’ but ‘a conviction and a challenge’ (Sanjukta Dasgupta on Mallika Sengupta). What she talks of Mallika becomes true of her as well. In Dasgupta’s poetry, too, ‘womanhood does not remain an interiorized awareness, it becomes an energetic protest against marginalization interrogating women’s position in society as the oppressed other’.(Dasgupta on Mallika) So, ‘Goodbye Mallika’ reminds all of Dasgupta’s words for Mallika which is also true of her own poetry as well. ‘Tell us Marx’, ‘Insignia of Blood’, ‘The Girl of the Sunlit Road’ are some of Dasgupta’s translated poems of Mallika Sengupta. Both of their views converge at a point- feminisms’ search for identity. Therefore, one must enter into Ekalavya’s world to confront life from various dimensions, to reverberate Virginia Woolf’s words on life (“Life is not a series of gig lamps symmetrically arranged; life is a luminous halo, a semitransparent envelope surrounding us from the beginning of consciousness to the end”) through the poems of Sanjukta Dasgupta.

Trayee Sinha is faculty at the Department of Women’s Studies,Diamond Harbour Women’s University, West Bengal.