Barq girti hai to bechare Mualmanon par (Ligtening strikes only on the Muslims) is a line written by the great poet Allama Iqbal as part of his poem entitled ‘Sikhwa’(complaint).

Perhaps the poem reminds us of the way contemporary Indian society continues to punish and persecute its Muslim citizens, humiliate them, violate their rights and treat them as second class citizens of the nation.

Years after partition they are told to walk down the other side of the border, their love for the nation is doubted; they are treated as traitors conspiring against their own country and are reduced into vote banks by the ‘secular’ parties. Amidst this complex social scenario what does it really mean to be Muslim?

While the lives of ordinary and simple Muslim men and women across the globe continue to remain full 0f hardship and difficulty as the world around takes it for granted that they are responsible for heinous terrorist attacks and all of them are necessarily conspirators against the state- a site such as a school is endowed with much possibility in such an ambience. The school as a site of knowledge and the promise to nurture and cultivate young minds with the seeds of freedom, diversity, equality and responsibility towards the whole of humanity, schooling does have the potential to nurture citizens who can build a peaceful and egalitarian social order.

The school is also an important agent of socialisation because it is the first formalised institution that the child steps into after the immediate family. Beyond the family and kinship networks, beyond ties of blood and association, beyond the boundaries of familiar languages and customs- the school introduces the child to the larger world where there is widespread diversity, where multiple cultures, languages, ethnicities, viewpoints and worldviews co-exist. The child learns that although someone may not be like her, she must respect her and work towards building a world where both of them have the right to expression as long as it does not threaten the existence of the other. Despite the tremendous promise that schools as institutions of socialisation hold, these days we are seeing how they are defeating their own purpose. Instead of cultivating the values of universalism, acknowledgement and respect for diversity, an understanding that the world is by nature heterogeneous and any attempt towards compulsive uniformity is undemocratic and making children understand that a threat on the existence of one cultural group is simultaneously a threat to the existence of all other cultural groups is the cornerstone of what a site such as the school was supposed to achieve.

Immense Capacity Put to No Use

Ironically, the school as a site of immense potential and an institution that helped cultivate universalism amid rampant parochialism, broad mindedness amid narrow thinking and free spirited and rational thought in the wake of fatalism is fast being replaced by a tendency to sow the seeds of narrow nationalism, parochial obsession and narrow definitions of identity from a tender age. Schools and playgrounds are increasingly losing their innocence and becoming trading points for cultural chauvinism and imposition of fractioned nationalism.

Hindu children are clean and obedient and Muslim children are lairs and unhygienic, Sikh students are violent and Jain students are weak and cowardly, Christian students have no morality, are alcoholic and come from broken families. These are some of the stereotypes that commonly define interactions within the school community. The butt of the joke is always the child from the minority community, he is alone and therefore vulnerable to being bullied based on the stereotypes that children from the majority group make about him. It is in this context that a wonderful book by the author Nazia Erum ‘Mothering a Muslim’ shows how even in India’s elite schools that boast of imparting rational and secular values, Muslim children face bully on account of their religious affiliations and are seen as the unwanted ‘other’. Their food practices, their cultural experiences and traditions, their religious practices accompanied by prevalent stereotypes about a Muslim youth’s likely affiliation to terrorist activities or anti-national conspiracy often make the process of schooling full of stigma and turmoil for many kids from the community.

Being Muslim in Contemporary India

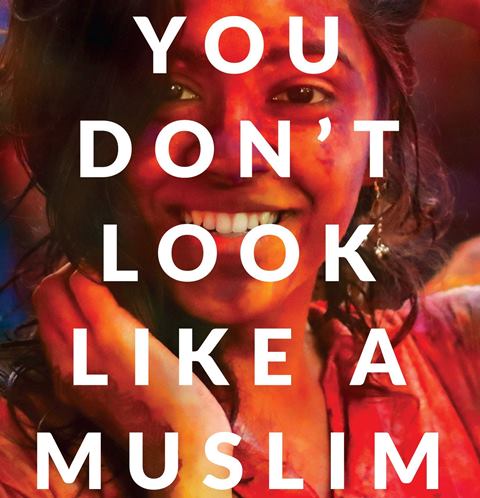

Another very beautiful account of what it feels like to be a Muslim in contemporary India comes from historian Rakshanda Jalil’s excellent book ‘But You Don’t Look like a Muslim’. In this book, she takes us on an engaging journey of what it feels like to be a Muslim in contemporary India and to delve deep into the complex layers of Muslim identity in such times.

What Jalil tries to do is to blend personal anecdotes with broader political concerns about how religious identities are perceived, transacted and politicized over time. The significant questions that Jalil raises in this book are about how in a culturally diverse country like India, how specific traditions and values mould people and determine the ways in which they perceive the larger world.

Jalil’s book talks to the reader, makes her ask important questions and makes her rethink her own perceptions about how Muslims are conceived of in a nation like India. She asserts how throughout her life she has continuously met people who have approved of her by saying that she does not look quite like a Muslim( as if Muslims were creatures from another planet bearing no resemblance to other humans!). The approval that is born out of a stereotypical conception of what a Muslim looks like is in itself severely problematic.

The popular imagination about Muslims is ironically that they are beef-eating, bomb-throwing, fundamentalist, jihad-spouting beings who are not to be trusted and taken seriously.

Jalil points out how culture and media have had an important role to play as far as the perpetuation of stereotypes around Islam are concerned. So from pan-chewing, kohl wearing, qawwali-singing Muslims of old films we witness more modernised caricatures of Islamic identity in contemporary cinema. What we find in films today are modernised sinister dons sitting in the Middle-East or in Pakistan, tech-savvy and English speaking directing terrorist attacks or playing the part of cold-blooded jihadists. In many recent films we have also seen how the Muslim boy as the male protagonist is seen as strategically entrapping Hindu girls in the name of love, killing and enjoying cow meat and being projected as a community of fundamentalist, old-school and regressive men and women who adhere to kutbas about regressive and irrational social practices. The popular imagination has reduced the average Muslim man into a regressive, fundamentalist, anti-national entity whose innate tendency to betray his own nation must be brought to centre stage by asking him to compulsively chant ‘ Vande Mataram’ or stand up for the national anthem in a jam-packed theatre hall.

Life for the average Muslim man or woman in our universities and work places, local trains and marketplaces, airports and cinema halls has become one of increased surveillance, heightened suspicion and growing objectification. The Urdu language despite its secular mornings and trajectory as one of secular origins has been looked at as only belonging to Muslims negating the significant fact that Muslims in Kerala speak Malayalam, those in Assam speak Assamese and those from West Bengal are fluent in Bangla.

The projection of Muslims as stuck in medieval past with their multiple begums and esoteric ghazals in lamp lit havelis or their projection as violent invaders who took away Hindu queens and destroyed temples- have barred us from understanding the community as a dynamic, diverse, transforming community like any other which has all kinds of people, diverse customs and cannot be seen as if it were a dead historical artefact.

The book highlights how culture, popular media, perceptions and stereotypes accompanied by the absence of dynamic and meaningful interactive spaces have led to congeries of evil being attributed to the Indian Muslims. Perhaps as we witness the holy month of Ramadan, it is important that we take note of all the uncouth and unholy practices that are breaking apart the secular and culturally enriched fabric of our nation.

It is time to debunk damaging stereotypes and look beyond irrational perception; it is time for one community to meet the other with an open heart. Let the politics around Islamophobia not make us blind to our shared historicity; let us understand that our future lies in peace.

Book But You Don’t Look Like A Muslim, Rakhshanda Jalil, HarperCollins India.