We experience the world around us as real and lasting. The things we perceive out there appear to really be there, seemingly enduring through time. But the world actually is not as it appears. Nothing lasts for more than an instant. Everything changes from moment to moment, and yet we still think that our perceptions are real and genuine. The more we get stuck in that way of thinking, the stronger our negative emotions will grow. And the more the emotions take charge, the harder and more painful life becomes.

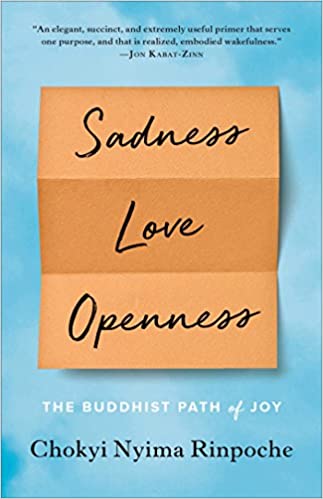

– Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche

In these strange and troubled times filled with psychic nausea and anxiety, I long for something deep and meaningful: beyond television news, statistics of death, and even the dry logic implicit in academic texts. And at this juncture, this slim book attracts my eyes; and almost instinctively I decide to buy it. I read. I reflect. I cry. I feel the light of illumination. I pass through a process of inner churning. Yes, Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche is a Tibetan Buddhist master; and it is not surprising that his profound art of communication touches our souls, and makes us understand the meaning of the Buddhist wisdom.

Well, it is not easy to accept that everything we are attached to is essentially transitory; nothing is permanent, and death is implicit in birth. It hurts us, causes immense pain or sadness. Moreover, our egotistic pride is centered on this attachment or sense of possession: I am my bodily strength or beauty; I am my material wealth or fame and power; or, the pleasure I experience right now is eternal. But then, nothing is permanent; a beauty queen will eventually become a skeleton; a mighty dictator will be thrown out of power; our closest and nearest ones too will disappear; and our power and wealth will not be able to resist our ultimate journey towards the graveyard. Yet, we close our eyes; we live with delusions; and, we think that, as American bestsellers would like us to believe, life is a picnic party.

Hence, the very idea of impermanence causes pain; we seek to escape from this truth. And this Buddhist teaching, we might even complain, is pessimistic; it causes despair and nihilism; or it deprives us of the vitality and zeal for life. At this juncture, Rinpoche seeks to awaken us. The realization and acceptance of this impermanence does not mean that we refuse to live; instead, it creates a new possibility of living deeply and meaningfully. Reflect on what Rinpoche is saying:

Sadness, of course, is not an end in itself. But deep sorrow comes with realizing that everything we previously took to be lasting and real is actually just about to disappear—and it never even existed in the first place. Such sadness and disillusionment have a wonderful effect. Sorrow makes us let go. As we stop chasing futile and ultimately painful goals, we embark on the spiritual path with superior strength and resolve. (p.31)

This is the ‘healing power of the Dharma’. In fact, this awakening that everything is impermanent, and everyone is subject to the same ‘merciless conditions’ generates an intense feeling of love and compassion.

Sorrow and pain become catalysts for deep-felt loving care, and the power of universal compassion delivers the realization of the true view. That’s when we have truly become students of the Dharma. (p.52)

Yet, it is not easy to become a true practitioner of the Dharma. Quite often, we live with ‘trivialities’: talking about the weather, making plans for the future, and purchasing the things we desire. There seems to be no end to this reckless desire: the desire to ‘own, build and invest’. But then, our fears have not diminished. Instead, as Rinpoche says, ‘we worry more’. It would not be wrong to say that ‘desire and selfishness are mental weapons of mass destruction’. Is there any way to free oneself from their grip? See how the Buddhist monk responds to this question:

What do we do once we have recognized that nothing lasts? Here is a simple and effective technique: Let go. Don’t hold on so tightly. The more you let go, the less it hurts. Let go entirely and the pain is gone. On the other hand, the more we grasp, the more painful it is. (p.74)

And this generates the possibility of ‘great love’ that heals and purifies. With this unconditional love, says, Rinpoche, all destructive emotions like ‘self-importance, greed, pride, doubt, and envy vanish, and all that is good appears.’

However, this is about deep awakening and realization. This is not an intellectual/academic exercise; nor is it a technical riddle. Intellectually, it is possible to say that everything we are attached to is impermanent. Yet, we fail to alter ourselves, and fall into the trap of selfishness and desire. But then, the more we acknowledge and understand impermanence, we begin to wake up with love and compassion.

The world we live in is intoxicated with greed and desire; and the all-pervading culture of consumerism seeks to makes us feel that we are what we possess. We live with psychic restlessness, envy and jealousy. The pleasures that the market creates are temporal; and some sort of emptiness, despite all these possessions, continues to haunt us. Yet, we remain hypnotized. But then, how wonderful it would have been had we truly realized:

I’m done. From now on, I want to see things for what they really are. I won’t be a slave to my own delusions anymore. I know my perception of the world is completely out of touch with reality. All my day-dreams and fantasies, all my worries and fears—they are trivial and pointless! (pp. 30-31)

Yes, despite my repeated failure to wake up, I value every word Rinpoche has written. He makes me feel that I should not give up my quest; and I must undertake the journey that a true practitioner of the Dharma celebrates—from sadness to love to openness.

Avijit Pathak is Professor of Sociology at JNU.

Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche, Sadness, Love, Openness: The Buddhist Path of Joy, Shambhala South Asia Editions, 2018.