FROM THE BOOKSHELF

Growing water crisis and mismanagement of water resources is certainly a concern that neither the nation-state nor the local communities can ignore, the book throws light into the complexities and debates involved.

Dr. Ramanujam Meganathan is an Associate Professor of English, Department of Education in Languages, National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT), New Delhi.

This book has convincingly answered the lingering question in my mind about how my hometown in Thiruvarur district, Tamil Nadu could experience severe drought or drought like situation during the summers when we were struggling for even drinking water.

With its four chapters the book examines the many blunders that the governments and people commit in the name of development, urbanization, modernization and growth and how even the drought relief programs are often at the cost of the environment.

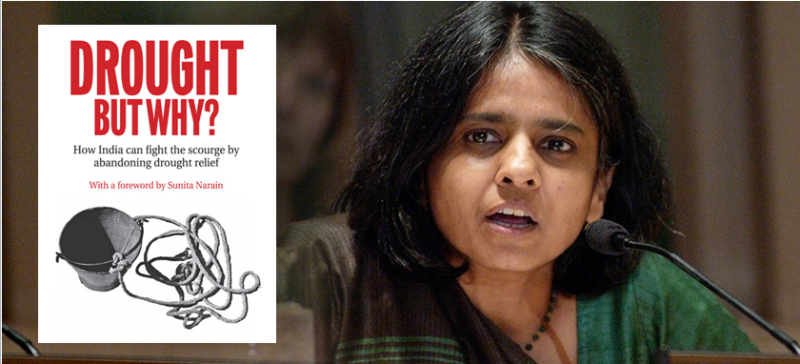

The central message that the book tries to convey is that droughts are man-made. Let’s look at a couple of the lines from the foreword by Sunita Narain, “The fact is that urban areas and industrial hubs in our part of the world are now putting greater pressure on water resources. Cities across the country need more water. They are more powerful. Their elected master works overtime to course water from far, and further, away. Delhi will get water from the Tehri dam, over 300 km away in the Himalayas; Hyderabad, from Nagarjunasagar dan on the Krishna river 105 km away; Bengaluru from Vauvery, about 100 km away. Udaipur used to draw its water from Jaisalmand Lake but it’s drying up. Add to all this industrial growth. Yes, the modern water economy is indeed on our doorstep.”

The conversion of the traditional water economy into a modern water economy has not necessarily yielded positive outcomes. In the traditional economy 70% of water is consumed by agriculture and the rest is for industry and urban areas. This has now been reversed. Hence the trouble is immense as Sunita Narain suggests.

‘Three Years 500 Million Victims, and an Epoch’, the first chapter explains how poor policies pushed India into one of its worst droughts ever. Illustrating from the current crisis of seemai karuvelam, Pjuliflora (in Tamil Nadu) which was introduced to afforest arid lands in South India in the 19th century has now become what the authors call a ‘villain’. People now want to root it out to escap its excess consumption of water and the court is questioning whether it was scientifically proven that trees could be responsible for droughts.

Citing the monsoon failures in the southern peninsula, the authors show evidence of how water harvesting from available monsoons could have served a much better purpose than what our policies have done. Bundelkhand and Marathwada regions and their droughts over the last two decades and the amount of money spent (15,000 crores and 21,000 crores respectively) resulting in no relief in terms of recharging water bodies or ways and means to provide any relief to land and people have proven futile. Likewise many regions such as Marathwada, Latur, Manwati show how water scarcity and deficient rain played havoc and government policies have resulted in perpetual failures.

[bctt tweet=”“Indian will be polarized on the lines of who captures rain and who doesn’t. In the face of climate uncertainties and lingering drought, catching water where it falls will be the religion of survival.”” username=”httpstwittercomthenewleam”]

Interesting illustration of cow slaughter ban and its environmental impact from the state of Uttar Pradesh has also been cited by the authors which reveals how the ecosystem and the consumer behaviors affect the environment alongside the economics. When the government banned cow slaughtering some village economies that had been dependent upon it suffered. Farmers could not find ways and means to maintain the old cows which would have otherwise, been sent to slaughter houses. The authors believe that government policies predictably go wrong and elucidate why.

The second chapter, ‘Drought by Appointment’ reveals how India’s drought prone areas are water rich. Technically flawed or unsuited structures to the terrain, wrong selection of reservoir location due to caste politics or regional affiliations are cited as major reasons for the failure of water storage systems and such systems not being implemented. The glaring example is Sakaria reservoir constructed at a cost of Rs 5.7 crore in Heerapur village of Madhya Pradesh’s Panna district. Quoting from village elders and formers, the authors bring out the real politics in the creation of water bodies like dams, both big and small, check dams and so on. The second chapter presents arguments of not only of farmers and village elders, but also water management experts and economists who feel that the water scarcity crisis and drought could have been averted or managed well as most of the drought prone regions were water rich.

Titled as The Dreamer and the dream catcher, the third part of the book bases its argument on the Prime Minister’s ‘dream’ statement on February 28, 2016 about doubling the income of farmers by 2022. The authors point that while this did instill hope in farmers, the reality unfolded differently. Farmer suicides and continual demonstrations by farmers across the country have stood testimony to their disillusionments. Some of these demonstrations, as we all know, resulted in shootouts and killing of farmers.

Moving from despair to hope, the authors present case studies of several villages that have meticulously and painstakingly stood above by rejuvenating, recharging water and bringing life back in their water bodies. Ralegan Siddhi village in Ahmednagar district and Hiware Bazar, Kadwanchi, Satara in Maharashtra and many more villages which with their traditional wisdom and modern technology and thinking were able overcome the water crisis are true examples of strong public will. Respecting and understanding the ‘nature of nature’ could be stated as one major reason for this success. Recharging during monsoon, budgeting water and not overdoing by digging bore wells beyond certain depths are some of the timely and righteous actions which saved these villages. The authors illustrate how the incomes in these villages increased, in some villages like Hiware Bazar.

The third chapter also presents how effective training can improve the yield and enable farmers to be more informed. The message here again is regarding the education of the farmers.

The final chapter, as expected, attempts to capture the lessons learnt from the blunders and the good practices. A statement in the opening page reads, “Indian will be polarized on the lines of who captures rain and who doesn’t. In the face of climate uncertainties and lingering drought, catching water where it falls will be the religion of survival.” These are probably the lines that need to be inscribed in gold for the governments, farmers, urban dwellers, shopkeepers and villagers “Don’t assume that you have inherited the world from you father and mother and remember you have borrowed it from your sons and daughter. So behave yourself.” The idea that is being conveyed here is how judicious management of water is indeed the need of the contemporary hour.

ALSO READ

Why I Should be Tolerant: On Environment and Environmentalism in the 21st Century

The book makes one understand how the mindless over use of water and mindless drought management systems have led to the crisis we encounter today and provide directions and solutions to overcome the crisis. It proposes that we learn from past errors. The book is a significant evidence based document. It is a book for the future to remember, use and consult and re-consult to understand and use water in moderation If I say this book should be a prescribed book for environmental education, environmentalists, researchers, students, teachers and teacher educators in schools and at the university levels it wouldn’t be an exaggeration. The book must also reach out to those in power and capable of making policy decisions.

This book exposes the hitting truths about water scarcity and drought which could have been and could be in future averted The stories of trauma of farmers and the succestruly insightful. And of course the minimal s stories of villages which have shown ways to preserve and recharge the earth are pricing of the book make it attractive for a wider range of audiences, who can be easily exposed to a rich and provocative text such as this.

Richard Mahapatra, Snigdha Das. 2017. Drought But Why? How India can fight the scourge by abandoning drought relief. Published by Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi. Pages 126. Price Rs. 240.

***

This article is published in The New Leam, FEBRUARY 2018 Issue( Vol .4 No.33) and available in print version.

If you Liked the story? Go ahead and support the cause of independent journalism. DONATE NOW