Beyond Technical/Instrumental Approaches: Connecting with People’s Humanity

Please tell us about your academic/intellectual trajectory. Today how do you see yourself as an educationist—a professor of education nurturing a new generation of teachers and researchers?

I often find it ironic that a key element in my trajectory was my dislike of most of my teachers and of the mechanical ways in which we were made to study. This drove me towards teachers, friends and organizations who exemplified greater authenticity and showed great commitment in engaging with the burning issues of our times. I initially did a B.Sc. in the life sciences and had found the study of plants and animals a wonderful thing, a source of great joy. But the idea of working under closer and closer supervision in laboratories and in large academic bureaucracies was depressing. So I moved to the social sciences, hoping to get a deeper engagement with all the troubling issues of violence and communal hatred that surrounded me and hoping also to find a way of study which was less claustrophobic. Studying Anthropology in Panjab University I was lucky to get a teacher like the late Divyadarshi Kapoor who inspired us with his sharp intellect, his academic rigour and his iconoclasm. Then at Jawaharlal Nehru University I had the privilege of having teachers like Avijit Pathak who exemplified a scholarship that embedded honesty and sincerity.

From under-graduate days I was lucky to have friends like Balram Bodhi and Gurinder Singh “Dimpy” who took stands on public matters and were not afraid of risking everything they had, including their lives, in support of issues of deep concern to them. When one thought of a future life, it was one of working with groups that struggled for a better India and a better world, not of being an academic. Slowly many of us began to feel that education was a domain of central importance in changing the world. When we looked at people’s reactions of cynicism or ignorance, we felt that perhaps it was through struggle in the area of education that some long-lasting changes could be brought. Rather innocently we thought that if you change children, you change world. Now, of course, one realizes how simplistic that understanding was.

Kalyani Dike, whom I was later to marry, introduced me to Syag bhai of Eklavya in Madhya Pradesh. Through him we got to meet many more people, Arvind Sardana, Anu Gupta, C.N. Subramaniam, Rashmi Paliwal, Yemuna Sunny, Sushil Joshi and so many others who seemed to be having a wonderful life, working in small towns to apply the deepest ideas of Indian social science to try and transform what children learned in school. This, Kalyani and I thought, was the way to live. It had the additional benefit of being away from the preening and pretences of academia, with the scope and freedom to reach out to the most fundamental questions without being distracted by having to play the games needed to keep academic hierarchies satisfied.

Given my interest in engaging with social change, I was drawn to Civics as the inevitable place within schools where a great many of our country’s problems could be confronted. But the problem was that most people found Civics quite boring and uninteresting. Typical of Eklavya was to ask the question why was it that children found Civics boring. My tack on that, while living in Hoshangabad, working with Eklavya, was to point towards a conflict within schools between different cultures of collective life. Talking to people over three years, running libraries, conducting workshops, interviewing insightful individuals, I began to argue that on the one hand there was a culture which emerged through the discourses of power of a caste society, emphasizing on the one hand equality between men within a caste group, but on the other hand hierarchies between them and women and other caste groups. Against this stood the culture which the school textbooks sought to convey, which spoke of all the values of the Constitution – universal equality, freedom, democratic processes and so on. The tension between these two cultures was so acute that the Civics curriculum became a potential battleground. That was why textbook writers intuitively deleted from it all that could be contentious, leaving only rules and regulations of the Indian state and pious injunctions which meant that we see no evil, hear no evil and do no evil. There was actually no attempt to build a dialogue between these two cultures. That was why the Civics textbooks became, to paraphrase the immortal words of Willard Waller, dessicated museums of virtue, lifeless and fleshless.

Later while working at IIT Kanpur I got interested in the ideologies of inequality in education. The sparking of this research interest came from Mandal II, when I was horrified and traumatized to hear the kind of things which many of my colleagues there said about non-upper castes. I was struck by the lack of historicization, the way social inequalities were sought to be justified and their naivete regarding how social structures forced people to underperform in education. There were several notable exceptions to this amongst my colleagues, but I began to realize that what I was encountering was a widespread culture of the Indian upper educated classes. Much later I read a book of popular economics called The Winner-take-all Society. I thought the title an apt description of this morality, whereby those who were at the top resented any challenge and found a million ways to criticize anyone else’s claim to a share of their pie, while closing their eyes to the arbitrariness and illegitimacy of their own claims. That experience drew me into debates over the character of merit and then towards a rethinking of the reservation system. I was fortunate in finding at Azim Premji University a very supportive climate for putting in place some of those ideas. Here we have tried to build a socio-economic disadvantage index using not just caste but eight different parameters for weighting the admissions of those with historical disadvantages.

With Eklavya, APF and many others I too wondered how education systems as a whole could be made more just and egalitarian. After all reservation was just a token band-aid to try and patch the wounds of a larger social and educational system. This was drawn me nowadays into trying to visualize what are the different forces which go into transforming education systems. A force which has tended to get less attention than it deserves is the role of politics, social movements and the ideologies of elites in shaping a society, including its education system. The sensitive and thoughtful Rama Sastry and B. Ramdas who are part of ACCORD and the Adivasi Munnetra Sangam have helped me to better understand that dynamics. NGOs, CSR and the state have a tendency to focus on bureaucratic and technical solutions. It is important keep reminding ourselves that we also have a political dimension to our lives and our society. This plays a key role in fixing priorities, in shaping what we see and what we overlook and in building collectivities which then take certain positions and not others.

I see my work as an academic partly from this perspective. It is part of a cultural politics in Indian society. By encouraging students and colleagues to look at the experiences of the oppressed we act against the hegemonies of the powerful. By celebrating the insights which come from theory we stand against the narrowness and blinders of technical-instrumental knowledge-interests. By emphasizing that the study of human beings and their relationships can lead us to a career and a meaningful way of life we help students escape from rigid cages of technocratic bureaucracies. By saying that radical critique, research, teaching and constructive action are not water-tight compartments but can all go together we stand up against the despair which pulls us into giving in and accepting dominant ideas and ways of life.

I may not have been able to do all of these particularly well myself in my own life as an academic. But I feel that even a small step in these directions helps in building the bricks of a larger transformation.

If we see the discipline of education as an integral component of the larger socio-political/philosophical discourse, where do you see the epistemological roots of critical/emancipatory pedagogy?

The way we talk about critical and emancipatory pedagogy in India probably comes from several epistemological origins. One source is certainly the way in which nineteenth century anthropology developed, particularly as seen in the works of Karl Marx. In his writings, for example, we find that human beings created themselves through their interaction with and struggle in the real world. They did not come into existence fully formed, but made themselves, in every sense of “made”. This making of our humanity had to endure several frustrations and blockages. In feudal times the creation of human beings and their fullest expression was blocked by feudal relations of domination which kept the vast majority in bondage and poverty. Under capitalism it is blocked by manipulative market relations and through cultural processes that lead us to give up our agency. The assertion of human agency, of human praxis is at the core of critical pedagogy and it is understood as having to struggle against a large social system of oppression for it to find expression. These are the ideas that resonate through the work of Paulo Freire.

We find here the notions of a false consciousness, of the idea that culture and understanding should be looked at with caution and not accepted at face value. The constitution of our understanding is shaped through our praxis and when that is being distorted our understanding and our imagination cannot escape unscathed either. Knowledge and practice must be engaged in an undominated way, that is perhaps what emancipation stands for.

Another source is that of American pragmatism, particularly the work of Dewey and his followers. Many in India who are reluctant to read Marx are willing to read John Dewey, Herbert Blumer, and George Herbert Mead. There too we find the notion that human action is what creates human understanding. A critical pedagogy from this point of view is one which encourages unconstrained interaction and thence a fuller, deeper understanding. The parallels with Marx are clear. Where a difference can be seen though is in the role of social structures in constraining interaction. While Dewey is willing to discuss questions of systemic constraints on our actions, we find greater scepticism amongst many others in this tradition.

In India the Ambedkarite and feminist movements have recently given a strong push towards a critical pedagogy. Both these movements – and sometimes they speak with one voice – have pointed out that cultural interpretations may be soaked with the colours of domination. Patriarchy and casteism have shaped students’ and teachers perceptions of their selves and the way school knowledges have been formulated. The questioning of these forms of domination have been a key element in the impact of these movements on educational debates in India.

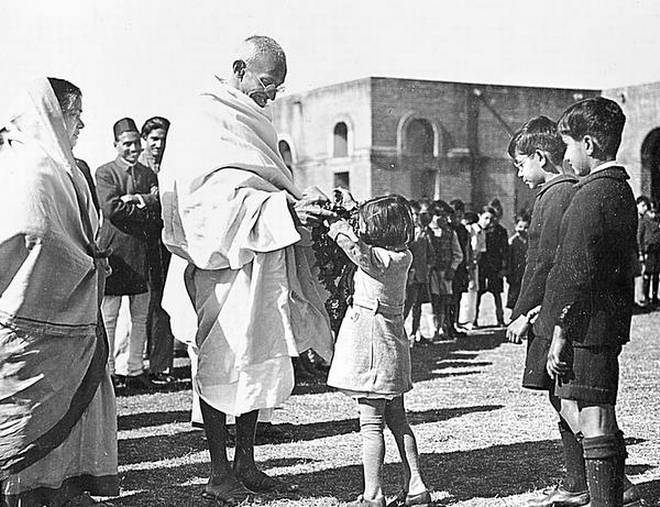

There are other strands, too, but perhaps one can stop with a mention of Gandhian roots to how we formulate a critical pedagogy. From Gandhi and many who have been inspired by him we get a profound questioning of what are seen as western, industrializing discourses. These imprison us by impoverishing our abilities to think and to fully make use of our bodies. They draw us to technologies that enslave rather than empowering us. The Gandhian critique of development and the trends which dominate school knowledge has led to asking what kind of education is needed to really free us and give us swaraj.

In this issue of The New Leam we have invoked Karl Marx, Ivan Illich and M.K. Gandhi because these thinkers/visionaries, we believe, inspired us to look at education and life from a radically different perspective. However, we are living at a time when we see an unholy alliance of neo-liberal market and social conservatism. Under these circumstances, is it possible to retain our faith in life-affirming education—not just market-oriented/skill-based learning?

What you have called life-affirming education is something which will not quietly subside, it will keep raising its head. In the years of the freedom struggle it spoke the language of Nai Talim, in the 1970s it spoke a language of empowerment and science popularization, in the current era it speaks in the voices of all those who wonder what is the purpose of education and feel drained and depressed in the classroom. This includes a large number of the students and teachers who have been sucked willy-nilly into technical and management education. The managerial elites have a favourite technique which they use again and again – to sing a song of triumph, of how great their institutions are and how wonderful their knowledge is and how great this nation will become. But the students who feel empty and hollow, the teachers who must resort to “professionalism” to retain their control in the classroom, understand in their hearts that something is missing.

The fundamental problem of technical-instrumental approaches to culture and education is that they are unable to reach out and connect with people’s humanity. This will keep leading to a questioning of what is going on.

But history cannot be determined by a grand calculus of social forces. We make our own history and again and again we find examples of groups, organizations, voices and movements emerging which startle the dominant logic. It is up to us to organize and build alternatives. We cannot take up an approach of fatalism, either giving up or waiting for history to somehow turn the corner by itself and change things. Many voices can survive together, waiting for their time to come, evolving and building a deeper understanding.

There is a paradox of information revolution. Yes, because of new technologies, we find ourselves amidst the abundance of information. Yet, there is an anxiety that the culture of reading—reading for sheer joy, reading good books outside the syllabus, reading great literature and philosophy—is declining. Furthermore, the pressure of exams and the culture of guide books that the chain of coaching centres encourages tend to restrict the imagination of young learners. How do you see this paradox? Or do you think otherwise?

I am a little ambiguous about this. On the one hand, yes, most of the books being read and sold in English are related to exams or “how to be successful”. But I still see a large number of people outside the social sciences and humanities reading other kinds of books – fiction continues to sell very well and there is a growing interest in history and other forms of non-fiction. Whatever we may think of these authors’ quality, in English the huge numbers of books which Chetan Bhagat and Devdutt Pattnaik sell reveals people’s desire to read mythologies and narratives which are outside the realm of the narrowly instrumental. It is relevant here to remember that a very large number of people have entered the world of readers in recent decades whose parents had never bought or even read a book before. Perhaps we need to re-invent the styles and forms of communicating so as to reach out to people. Maybe the older forms of writing have to be adapted for a new generation. There is nothing surprising, of course, in styles of communication changing over the years. If I try to read even great authors like Tolstoy or Herman Melville today I find them rambling on and on in comparison with the narratives of more contemporary authors. Styles must change with time.

When I look at young people using the internet, again I wonder about the possibilities there. They are not just reading technical materials on their mobiles, tablets and laptops. Indeed by far the greater amount of time is probably spent reading blogs, news and on the social media. This is a sign of an interest in human affairs and a deep involvement in the lifeworld. I find young people circulating videos and photos which they respond to in an emotional and aesthetic manner and spending hours exchanging comments and remarks with friends. The surprising popularity of Ted talks and many other videos which are not just mindless entertainment amongst people who refuse to open a book may be telling us something. Perhaps as technology has made the visual image cheaper to produce and consume the sheer power and impact of it is making the image rather than the word become the vehicle which people turn to when they seek to make meaning of their lives and relationships.

At one point in history, with a specific configuration of technology, the book was the site where intellectuals interrogated their times. Great thinkers like U.R. Ananthamurthy were widely read by a literati for whom his books were sources of inspiration and also sometimes anger and rejection. Without wanting to underplay the politics of the internet and the way certain discourses get privileged in it, perhaps we are now seeing a time where locations other than printed books are also sprouting and those who wish to be part of the churning of ideas should learn to communicate at those locations, too. If Facebook and Youtube are where a great number of people are sharing their thoughts and their critiques of contemporary times, then it makes sense for those who want to reach out to others to try and learn the art of communicating there as well.

We would like to know something about your intervention—the way you invite your students to the world of good books, deep educational philosophies and innovative pedagogic practices. And how do they respond? Is it a moment of convergence or dialectical dialogue?

I am not, unfortunately, a teacher who is very deliberate and aware of all he does. There are friends and colleagues who can theorize quite well what they do and then also teach in direct line with their theories. But I find it difficult to describe or explain and justify what I do. Let me just talk about two aspects – the meaning and appeal of the content of what I teach and the need to give space to students.

Perhaps one thing I do a lot is to try and translate the abstraction of concepts and theories into living, emotional, vivid examples. That living everyday struggle is for me the reason to study the questions that I have been engaged with for many years. There are some people who have managed to train themselves to seek answers to certain questions on purely formal grounds or because they find some external benefits from doing so. I am unable to do so and cannot visualize students doing that either. The reason to study and closely think about an issue must come from its personal or even emotional appeal, from the practical challenges it raises, from the deep moral dilemmas it poses, both in a historical sense and in daily activities. So those concerns are what I try to draw into the classroom whenever I teach. The more creative and time-consuming part of preparing for a class is trying to find the right way to pitch the appeal of a theme and the meaning of its different aspects. Sometimes this approach bombs and sometimes it works. On the days that it works it seems to stimulate a lot of autonomous thinking and reading by students, when they begin to find themselves too quite concerned about those issues. One aspect I try to keep in mind in my conversations in the classroom is “what can we do about” an issue. Merely to analyze something seems idle and self-indulgent. To keep at least one foot in what people have done about it or what are the possibilities of acting in that domain, this seems to give the class momentum and a sense of purpose.

I was usually a skeptical student myself so even now I do not assume that by virtue of being an officially appointed teacher I automatically have something important to say to the students. I have something to say which is important to me, but not necessarily to them. By the end of a course I usually express my gratitude to the students for their attention. If through they course they begin to feel that these are matters which they, too, feel concerned about, then I can think my efforts were worth it. But, of course, I cannot assume that this is just because of my own effort, so many factors may be involved. Against this, there are also students who don’t find the things I am talking about worth investing their energies or thoughts into. Or there will be those who find my assignments of lesser priority than other interests they may have. Taking a punitive approach to them is pointless. How can one scold or coerce someone into finding something interesting! Instead I try to find issues and examples which can draw them in. Sometimes it works, sometimes it does not. Perhaps teaching like any other cultural performance is a highly culturally specific act. Sometimes one is having a conversation within the happy chance of a completely shared set of cultural premises. But sometimes one is talking to another culture and there a slow process of dialogue has to be developed, which, of course, transforms both sides. At all times one has to respect the other’s point of view and not insist too strongly that my own culture is fundamentally right and superior. The moment one does that it ceases to be a dialogue and becomes an imposition. Yes, students may respond to even an imposition by caving in and beginning to accept your position. But that is now an act of domination and what is forming is a sado-masochistic bond. I would much rather that we learn together as friends. I never liked domineering teachers and I don’t want to become one myself.