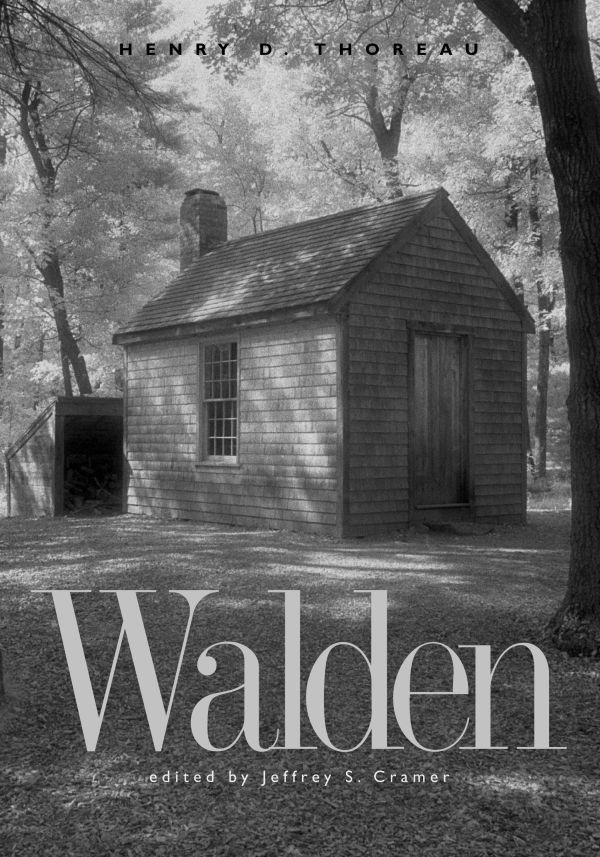

Henry David Thoreau was born in Concord, Massachusetts, on July 12, 1817. Between 1845 and 1847 Thoreau lived in a cabin he had built himself on his mentor Emerson’s property, near to Walden pond. He moved in on July 4, 1845—his personal Independence Day. Thoreau called the move an experiment, to test the transcendentalist idea that divinity was present in nature and the human soul. In order to get closer to nature, he stripped his life to the barest of essentials. He grew his own beans, wore only the simplest of the clothes, and generally tried to seclude himself from the rapidly industrialized world growing up around him. What arouses our interest is the striking similarity between Thoreau and Gandhi. Yes, we know that Gandhi was heavily influenced by Tolstoy, Ruskin, Emerson and Thoreau.

Here from Thoreau’s masterpiece Walden we have chosen four paragraphs.

As the reader goes through these paragraphs he/she is bound to see the convergence of ideas. Yes, like Thoreau Gandhi was equally apprehensive about the industrial civilization—its ruthless mechanization, its alienation from Nature, its dependence on artificial needs. Imagine Gandhi’s remarkably penetrating text Hind Swaraj which he wrote in 1908. See the following paragraph from Hind Swaraj, and compare it with what Thoreau wrote:

Let us first consider what state of things is described by the word ‘civilization’. Its true test lies in the fact that people living in it make bodily welfare the object of life. The people of Europe today live in better- built houses than they did a hundred years ago. This is considered an emblem of civilization, and this is also a matter to promote bodily happiness. …Men will not need the use of their hands and feet. They will press a button, and they will have their clothing by side. They will press another button, and they will have their newspaper. A third, and a motorcar will be waiting for them. They will have a variety of delicately dished up food. Everything will be done by machinery. … Now men are enslaved by temptations of money and of the luxuries that money can buy. … Formerly people had two or three meals consisting of home-made bread and vegetables; now they require something to eat every two hours so that they have hardly leisure for anything else. … This civilization is irreligion, and it has taken such a hold on the people of Europe that those who are on it appear to be half mad. They lack real physical strength or courage. They keep up their energy by intoxication. They can hardly be happy in solitude.

Voluntary Poverty

Most of the luxuries, and many of the so-called comforts of life are not only not only indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind. With respect to luxuries and comforts, the wisest have ever lived a simple and meagre life than the poor. The ancient philosophers, Chinese, Hindoo, Persian, and Greek, were a class than which none has been poorer in outward riches, none so rich in inward. The same is true of the more modern reformers and benefactors of their race. None can be an impartial or wise observer of human life from the vantage ground of what we should call voluntary poverty. … To be a philosopher is not merely to have subtle thoughts, nor even to found a school, but so to love wisdom as to live according to its dictates, a life of simplicity, independence, magnanimity, and trust. It is to solve some of the problems of life, not only theoretically, but practically. The success of great scholars and thinkers is commonly a courtier-like success, not kingly, not manly. They make shift to live merely by conformity, practically as their fathers did, and are in no sense the progenitors of a noble race of men. But why do men degenerate ever? What makes families run out? What is the nature of the luxury which enervates and destroys nations? Are e sure that there is none of it in our own lives? The philosopher is in advance of his age even in the outward form of his life. He is not fed, sheltered, clothed, warmed like his contemporaries. How can a man be a philosopher and not maintain his vital heat by better methods than other men?

Austerity and Simplicity

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I come to die, discover that I had not lived. I do not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quote necessary. … Our life is frittered by detail. An honest man has hardly need to count more than his ten fingers, or in extreme cases he may add his ten toes, and lump the rest. Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or thousand; instead of a million count half a dozen, and keep your accounts on your thumb-nail. … Simplify, simplify. Instead of three meals a day, if it be necessary eat but one; instead of a hundred dishes, five; and reduce other things in proportion.

True Needs

For my part, I could easily do without the post-office. I think that there are very few important communications made through it. To speak critically, I never received more than one or two letters in my life—I wrote this some years ago—that were worth the postage. And I am sure that I never read any memorable news in a newspaper. If we read of one man robbed, or murdered, or killed by accident, or one house burned, or one vessel wrecked, or one steamboat blown up, or one cow run over on the Western Railroad, or one mad dog killed—we never need read of another. One is enough. If you are acquainted with the principle, what do you care for a myriad instances and applications? To a philosopher all news, as it is called, is gossip, and they who edit and read it are old women over their tea. Yet not a few are greedy after this gossip. There is such a rush, as I hear, the other day at one of the offices to learn the foreign news by the last arrival, that several large squares of plate glass belonging to the establishment were broken by the pressure. … Shams and delusions are esteemed for sounder truths, while reality is fabulous. If men would steadily observe realities only, and not allow themselves to be deluded, life, to compare with such things as we know, would be like a fairy tale and the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. If we respected only what is inevitable and has a right to be, music and poetry would resound along the streets When we are unhurried and wise, we perceive that only great and worthy things have any permanent and absolute existence, that petty fears and petty pleasures are but the shadow of the reality. This is always exhilarating and sublime. By closing the eyes and slumbering, and consenting to be deceived by shows, men establish and confirm their daily life and routine everywhere, which still is built on purely illusory foundations,.

Truth and Sincerity

Rather than love, than money, than fame, give me truth. I sat at a table where were rich food and wine in abundance, and obsequious attendance, but sincerity and truth were not; and I went away hungry from the inhospitable board. The hospitality was as cold as the ices. I thought that there was no need of ice to freeze them. They talked to me of the age of wine and the fame of the vintage; but I thought of an older, a newer and purer wine, of a more glorious vintage, which they had not, and could not bu. The style, the house and grounds and ‘entertainment’ pass for nothing with me. Called on the king, but he made me wait in his hall, and conducted like a man incapacitated for hospitality. There was a man in my neighborhood who lived in a hollow tree. His manners were truly regal. I should have done better had I called on him.

- Henry David Thoreau, Walden

This article is published in The New Leam, March Issue( Vol.2 No.10) and available in print version.