OPINION

In this lucid piece the author has referred to Mr. Shashi Tharoor’s remark on a ‘Hindu Pakistan’, and reflected on the politico-cultural and psychic dangers implicit in the idea of militant religious nationalism.

Avijit Pathak is a Professor of Sociology at JNU, New Delhi.

Avijit Pathak is a Professor of Sociology at JNU, New Delhi.

[supsystic-social-sharing id=’5′]

Mr. Shashi Tharoor’s warning that the the society we are creating–particularly, after the rise of the assertive Hindutva politics– is likely to become like a ‘Hindu Pakistan’ has caused widespread controversy. Yes, Pakistan, we are repeatedly told by the bunch of hyper-nationalists–is an ‘enemy’ state: Islamic, fundamentalist and totalitarian. To equate ‘Hindu’ with Pakistan, as it is argued by noisy television anchors and superficially smart spokespersons of the ruling party–is a blunder, an insult to the glory of the nation, and hence Mr. Tharoor, as it is demanded by the Establishment, must apologize!

I am not a fan of Mr.Tharoor. Yet, I would argue that when he spoke of the possibility of a ‘Hindu Pakistan’, he meant the danger of a totalitarian society legitimating itself in the name of ‘Hindu rashtra’. He, I assume, did not insult Hinduism, nor did he diminish the sanctity of Indianness. He was critiquing an ideology of nationalism that is based on the hegemony of the dominant religion in a diverse and plural society like ours. And it is important to debate, to think, to generate a possibility of multiple and even conflicting perspectives in a democratic society. However, to diminish Mr. Tharoor as ‘anti-Hindu’ or ‘anti-national’ is to create a monoculture; paradoxically, it proves Mr.Tharoor’s point. In this small piece, I wish to make three points which, I believe, are often missed in the rhetoric of television panel discussions and ‘Congress-BJP conflict’.

Nation – no monopoly, please

A nation is not something fixed or given. We create it, we define it, we alter it. It is a continual process; every day all of us -peasants and workers, women and men, Dalits and Brahmins, Muslims and Christians, Hindus and atheists -are trying to shape it, restructure it, debate on it.

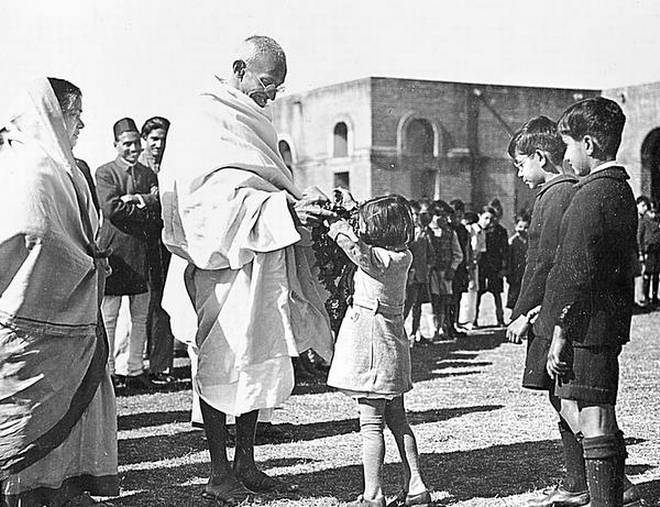

Take a simple illustration from history. Gandhi’s idea of the nation was not exactly similar to that of Nehru. Likewise, Ambedkar differed from Gandhi. Yet, we all realize that these very differences, these multiple approaches generate a non-dogmatic/pluralistic character of the Indian nation. Is it ever possible to say that Maulana Azad was less nationalist than M.S Golwalkar?

Or would it not be foolish to claim that Buddha’s egalitarian compassionate religiosity, the contributions of Islamic tradition and heritage, and the philanthropic work of Christian saints have no role to play in the making of India? The tragedy is that today the ruling regime wants us to believe that it alone possesses the nation; it is the only protector, only defender, only moral guardian of the nation.

This confusion of the ruling ideology with nationalism is desperate; from the heavily engineered social media to the aggressive propaganda machinery – the message is communicated to all of us that to differ from the ruling ideology is to betray the nation; it is like becoming ‘anti-national’. See its danger. You are not just against the policies of the Modi government; you are against the nation itself. In other words, this is like stopping all alternative voices, all dissenting notes; this is like sanctifying the ruling ideology in the name of sacrosanct nationalism; this is like monopolizing the nation. And this is dangerous. Because it eliminates all alternative voices by creating an emotionally charged idea of loud nationalism. ‘I am a nationalist–a legitimate child of ‘Bharat Mata’; I cannot be wrong; if you disagree with me, you are destroying your nation!’ This thinking is absolutely monolithic containing the seeds of a fascist mindset.

[irp]

This is the time to generate a counter-argument. Even if we are not with the ruling ideology, we are no less patriotic; through our productive labour, creative practices, dissenting voices, humanistic struggles we too enrich the nation, add to its meanings and possibilities. Medha Patkar does it in her own way; a Christian missionary nursing the leprosy patients does it beautifully; a Muslim tailor designing the clothes for Bengali women during Durga Puja is recreating the nation. No, it is not just Mr. Modi or his over-dramatic defender Mr. Sambit Patra who is the only nationalist around; even the likes of Shashi Tharoor have legitimate space in this expanded canvas.

Complex dynamics of our social practices

What does it mean to be a ‘Hindu’? Does it mean that all Hindus constitute a shared/caring/inclusive community? Certainly not. Open your eyes, and feel the falsehood implicit in the idea of a shared Hindu community. Yes, I am a Hindu. However, this does by no means assure that Hindu real estate mafias would not cheat me. Or for that matter, is it possible to imagine that the Hindu Ambanis of the world would create a paradise for Hindu workers?

Hindu patriarchs oppress Hindu women; Hindu bureaucrats accept bribe from Hindu citizens; Hindu casteists humiliate Hindu Dalits. In other words, in the real domain of the phenomenal world we see caste, class, gender and other identities that shape people’s practices. The idea of an over-arching Hindu identity hides the actual contradictions in the society. And it is not just about the ‘Hindu community’. Think of ‘Muslim community’. This too is hierarchically divided on the basis of caste, class and gender.

Even if you find a Muslim domestic help in a middle class Muslim household, you realize that they live in two different worlds; the shared ‘Muslim identity’ does by no means make the situation of the domestic help better than that of a Hindu domestic help. In fact, it would not be entirely wrong to say that the politics based on the centrality of the religious identity is some sort of ‘false consciousness’.

Well, this is not my contention to say that religious identity does not matter in one’s life; and we are all the time governed by caste/class/gender. We live in multiple realities. Take two living illustrations. Suppose I am moving around the city of New York, and I happen to see a beautiful Krishna temple. It is possible that in the distant land as a Hindu I feel like visiting the temple, spend some time, and buy a fresh copy of the Bhagavadgita. But then, as a professor I may feel more tempted to have dinner with another ‘Muslim’ or ‘Christian’ professor, rather than a Hindu priest. In other words, my social practices emerge out of the complex dynamics of multiple identities I live with. The plurality of possibilities within me makes me something more than just being a ‘Hindu’ or a ‘Muslim’.

This is the reason why the idea of a ‘Hindu nation’ or an ‘Islamic nation’ is inherently problematic. It hides cultural/political/economic contradictions in a society; it forces one-dimensional thinking; and above all, it eliminates the possibility of compassion that transcends religious identities–say, a’Hindu’ peasant meeting a ‘Muslim’ tailor, and fighting a shared battle for quality education for their children. Instead, it divides, and diverts the attntion from the real problem to an imaginary one. The Ambanis and the Adanis of the world become richer, and my children feel the threat of perpetual insecurity and joblessness; but then, instead of seeing the roots of the problem in the political economy, I begin to target the Muslims–see their population is increasing, with the flow of money and weapons from Pakistan and the Middle East they are conspiring; and everything will be solved if through mob violence and lynching I can finish them, kill a Muslim weaver or a Muslim fisherman! Let them die; let the corporate empire prosper! Be it Hindu fanaticism or Islamic fundamentalism, the character of the poison remains the same.

Religion as uniform; religiosity as transcendence

What is the meaning of ‘religion’ in this religion-centric politics? It is like wearing a standardized uniform; it is like differentiating oneself from others. I am a ‘Hindu’; you are a ‘Muslim’; our needs and emotions are contradictory; never can we converge into the rhythm of shared humanism. This is the politics that the likes of Savarkar nurtured; and Jinnah was not different. This erects a huge wall of separation; violence is its inevitable outcome. Well, it is possible to say that religions differ in terms of beliefs, rituals and practices. For instance, as a Hindu it is relatively easier for me to feel at ease with the celebration of Diwali; and it may be somewhat difficult for me to prepare the kind of food that my Muslim friends offer during Eid. It is because of certain kind of cultural heritage, that my name is Avijit, not John or Irfan. Likewise, whereas my daughter’s name is Ananya, my Muslim student’s name is Zarine. However, these differences need not be seen as obstacles; to live meaningfully is to remain sensitive to differences and plurality of rituals and social practices. The problem with the fundamentalist politics is that it hates differences; it annihilates ‘others’.

At this juncture when religion has been hijacked by the champions of fundamentalist politics, it is important to make a distinction between religion as uniform and religiosity as transcendence. At a deeper level, the highest expression of religiosity takes us to the transcendental domain of oneness – the infinite that embraces all, the awareness that generates love and compassion, the clarity that makes one see the Truth manifesting itself in multiple forms. While Savarkar and Jinnah reduced religion into uniform, Ramakrishna, Kabir, Rumi, Buddha and Christ sought to take us to the realm of enchanting religiosity: an experience of love and oneness amid apparent differences.

It is sad that all that is happening in the name of religion is destroying the beauty of religiosity. For how long should we allow ourselves to fall into the trap of the ugly rhetoric of ‘Hindu fraternity’ and ‘Muslim conspiracy’?