As a teacher who stays on campus, the past few months have been quite difficult for me; the campus without the vibrant energy of the students seems like no campus at all. There is a pulsating silence which resonates from the once warm corridors which used to be strewn with bits of laughter and youthful banter. The shift to the online modes of teaching precipitated by the global pandemic of corona was more or less smooth in my university, but most teachers yearn to return to the familiarity of the classroom even as they grasp at the lengths and breadth of online tools to make the classes more interactive and engaging. The shift to digital classrooms across India have further marginalised those who were already on the margins owing to the huge digital divide in India with only 23.% of households having access to internet according to a 2018 report on Social Consumption Expenditure by the National Statistical Survey report. On the other hand, we cannot also have a complete lockdown in terms of education as the loss of teaching and learning hours will lead to a crucial loss for our students, particularly as the job market has become more competitive than ever. As the say, the show must go on; and though we may be weary and crisis ridden, it is indeed time for us to put our poker faces on to tackle the battles that lie ahead. It is with this mantra and attitude that I started my journey towards becoming an online educator. The journey so far, from March to August) has been a bitter-sweet one with moments of utter despair and endearing gratification.

The initial period was one of exploration and curiosity as I experimented with multiple online platforms such as Zoom, Google Chatrooms, Moodle and Fb livestreams. Most of the students were quite cooperative bearing with my archaic computer-skills and a few even helped me navigate the world of virtual monsters patiently teaching me to use online survey, poll and other digital tools. It was also a period when a lot of us started using social networking and micro blogging sites to connect with our students. In the absence of canteens and college grounds, the cafeteria debates shifted online. I soon became proficient in the language of memes and the semiotics of trolls. There were also changes in the nature of the classrooms. Many of the students who were introverts in the campus started asking relevant questions in class and blossomed into extroverts in online chatroom debates. A certain anonymity provided by the digital screens and the slight pauses offered by the typing of answers gave them a new found confidence. The absence of tone policing and direct peer pressure must have also helped them. A lot of classroom pranks also shifted online with students annotating my ppt presentations at times to the chat box being flooded with wishes on birthdays and anniversaries. The lines between work and home had already been blurred and several female colleagues with children found it very difficult to manage their children’s online school hours with their own teaching hours. Some of us found comfort in books and caught up on reading and movie-watching which had been shelved for a long time.

It was in early March, that I got rattled out of this comfort zone of online smugness and all it took was a single phone call from one of my students with a small request. My heart sort of got ripped out as the student who I had marked as absent( as she had only attended 5 minutes of class) called me up later to request not to deduct her attendance as she had run out of data and could not afford to recharge it. She also told me that her grandparents were sick and their medicines’ cost had doubled over the last 2 weeks of complete lockdown because govt dispensaries were no longer open. It was a telling moment to learn about privilege and how it always works in the favour of those with capital and power! In a country like India, universities sometimes stand as monolithic edifices where all social and economic differences are white washed out under the garb of knowledge capital; it is assumed that if you can afford a university education, you are by default from a more or less financially sound family. It takes a moment like the one mentioned to make us realize that there are also those families which use up all their savings to send their children to these educational institutions and how something like the country wide lockdown can upset the household budget so much so that they have to choose between wifi and medicine. It was also a wakeup call to the pressure that our young people are under, of bearing the dreams of their families and also dealing with the loss of their support system offered by friends and the college campus – and also to the immense responsibility of the teacher in helping them achieve them and to tide through this difficult time.

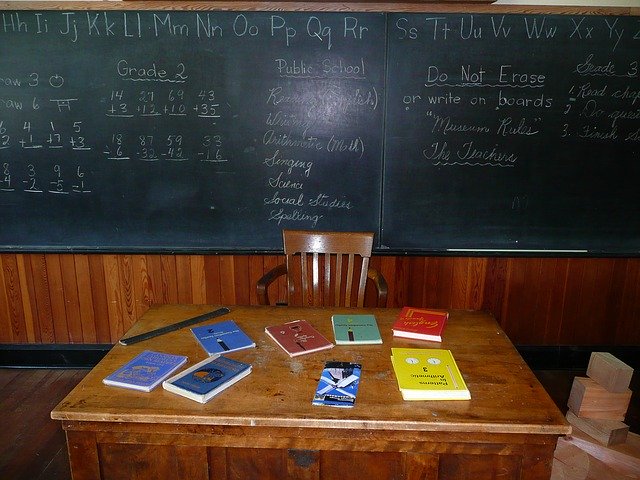

Indeed online teaching is difficult, the teacher’s toolkit is missing some of its essential tools. We no longer have visual cues from the students on whether they are understanding the class or not, we realise today that the lighter moments in class were luxuries of the pre-pandemic times, we miss the intense gratification after one sees a story or a concept sparking up in the eyes of a student, but our students probably have it harder. Long hours in front of mobile or laptop screens while being cooped in homes (with at least a section among them having to bear with abusive parents), the loss of privacy and absence of spaces which were their turfs in college along with the stress of an impending employment crisis due to the economic slump – it is certainly not easy to be a student in the pandemic times even if you have access to online education. Several female students also mentioned about them being given an increased and disproportionate share in household labour particularly that of looking after smaller siblings. The college or the university hostels were also spaces of liberty for female students, particularly from conservative families and the sudden loss of the same seem to have impacted them mentally and emotionally. It is important for teachers to be compassionate and to realise the academic and everyday struggles of the students. While small gestures like not compelling them to switch on their videos if they wish do not wish to or letting them take snack breaks when attending long lectures play an important role, but there are larger questions that needs to be asked about the best pedagogical practices to be followed in online teaching. In the debate for and against online education in India, we have missed asking questions about the content of the online education, whether present curricula can be fulfilled in the absence of labs and classroom discussions and whether the present syllabus is suited to the crisis situation. As the possibility of a vaccine still seems elusive and with most states adapting to a new notion of normalcy, we should also be flexible to adopt new strategies of teaching and learning. It is not an easy question to answer, but then the best teachers always ask the most challenging questions!

Malavika Binny is Assistant Professor at the Department of History, SRM University, Andhra Pradesh.