The anxiety attached to gift giving is worth considering. The Christian commemoration of Christmas is about celebrating God’s ultimate gift, his only son. Such an exceptional gift reaches its destiny in the crucifixion of Jesus: a sacrifice that can never be acquitted. The extraordinary nature of this gift, which ends in death, is resonant of a debt economy.

Capitalism is sustained through a debt economy of profits and arrears that spin endlessly in keeping the many beholden and the few prosperous.

During the festive season, it is clear that the sacred and the secular share an unholy alliance through their generation of a gift economy that leads to indebtedness.

If we think of Christ as a gift, the opportunity for reimbursement is slight. Mortals cannot match the divine offering, only revere and give thanks to it.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsThe secular gift also poses problems, for we are inclined through politeness to return in equal measure the kind of generosity shown to us. This brings to mind Søren Kierkegaard’s insightful claim in Fear and Trembling (1843) that it is far more difficult to receive than to give.

One might wonder then if the true gift exists? That is, a gift which does not make us feel indebted, beholden, or, dare I say, even guilty?

Perhaps a better way of approaching this question is to consider the great work of philanthropic charities – both religious and otherwise – that try to address social and economic inequality. Certainly spending both one’s time and money with friends and family over the festive season should give us pause to think of those who do not have these things.

Other kinds of altruistic gifts include anonymous donations, as well as the very personal act of organ donation.

These sorts of gifts are certainly worthy of our praise as they fall within the realm of what is virtuous and ethical. But do they succeed in cancelling our sense of indebtedness?

Such humanitarian examples do not address the heightened commercial activity that begins months before December 25 and which reaches its climax in the January sales.

Wikimedia Commons

Perhaps the annual January sales give prudent shoppers the opportunity to give to themselves – something which has become a consumer ritual over the years. Does this version of the post-Christmas gift eradicate indebtedness? Certainly the guilt of consumption is assuaged by the notion of acquiring a bargain.

During the festive season, there is also a conflict and collision between the secular and the sacred. For those more spiritually minded, it is a time for quiet reflection. For others trying to eke out a retail existence it is an important period of debt recovery.

This tension and anxiety over material and immaterial gifts has also been the source and subject of influential Christmas narratives.

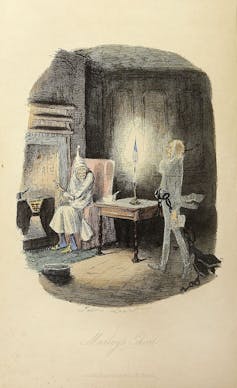

Take Charles Dickens’s famous morality tale A Christmas Carol (1843), in which the miserly old Scrooge learns to change his ways by the intervention of benign ghosts who show him the fruits of his meanness. In this story the spirit of Christmas is about being kindly and generous, so that one in turn receives benevolence.

In fact, there are innumerable Christmas fables that provide variations on this theme. Another classic example is Frank Capra’s film It’s A Wonderful Life (1946), where the hero of the tale played by Jimmy Stewart contemplates suicide on Christmas Eve only to reverse his decision by a benevolent angel once he is made aware of how much his life has made others happy.

Wikimedia Commons

Both of these narratives carry the Christian messages of showing others goodwill, kindness and compassion. The kind of generosity dramatised in each tale may not revolve around the exchange of material goods, but nonetheless the significance of the monetary offering cannot be understated.

This is particularly important to Jimmy Stewart’s character, George Bailey, whose bankruptcy is the cause of suicidal thoughts. This is exacerbated by his belief that his life insurance policy will at least save his family. On the other hand, Dickens’ Scrooge plays a shrewd capitalist who initially values money over family and friends only to realise the incalculable pleasure of being kind to others.

Bailey and Scrooge come from opposite ends of the gift-giving spectrum, but in the end each learns through the agency of a celestial messenger how important it is to be able to both give and receive.

It’s a Wonderful Life was Capra’s personal favourite film, and, like Dickens’ influential story, it is often broadcast at Christmas time. In both narratives each protagonist learns an important lesson. Yet however morally commendable and valuable these messages are, the real-life problems of abject poverty cannot be ignored.

These Christmas fictions and many others like them may provide us with pleasing conclusions where the good are rewarded and the bad see the error in their ways. Yet the fact remains that capitalism’s debt economy means that most of us will always be duty-bound.

The promise then of the pure gift that asks for nothing in return, and which releases us from the anxiety of obligation, remains an ideal yet to be realised.![]()

Suzie Gibson, Senior Lecturer in English Literature, Charles Sturt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.