It would be a great idea to look at the NEP document with a third eye. It is important to ask the question as to why many ideas, progressive on paper, are unlikely to be implemented. The real debate is in the analysis of structural challenges and whether the response to this would be greater engagement with the public system or the easy route of privatization.

(a) Looking Under the Rhetoric

Let us take some examples of how this may work out. Consider the reform of early childhood education. These ideas have been on the drawing board for years, at least more than a decade but why are they not being implemented? It is suggested that a preparatory class for children of age 5 be added to the primary school such that a link to class 1 & 2 of the primary school is established. This used to be an earlier practice called kachi paheli for government schools. Hence two years of learning center activities of Aganwadi, one year of preparatory class of the primary school and then class 1 & 2 of primary would in all make it one continuum of 5 years from age 3-8. This is what is suggested. The focus would be ECCE. Sounds reasonable. Why would this not work?

The ICDS programme run by the department of Women & Child Welfare is supposed to organize supplementary play school activities at the Aganwadi centers that they run. These centers themselves have a load and are very poorly managed so that supplementary activities take a back seat-they don’t happen.

There’s however a rich history of experience in the country in many states & across decades that could guide us as to how such centers should be run- what kind of play school activities to be organized and how to draw community support for doing this. The learnings of various organizations that have worked with these centers or set up their own has been very encouraging. There’s both theoretical work and ground experience. The precondition is that the center must function properly for its basic purpose of nutrition. If ICDS centers don’t function well, supplementary activities are unlikely to happen. The development of the brain is first linked to adequate nutrition, love and security. It is assumed that they are functioning in a reasonable manner. There’s no analysis here of the deplorable present state of affairs.

A community health doctor friend who has years of experience of these Aganwadi centers often tells me that there’s pressure on staff not to report severe malnourished cases, huge vacancies are not filled and in some regions centers hardly open.

A recent report by Accountability Initiative and Center for Policy Research states: (See below)

“The number of children receiving Supplementary Nutritional Programme (SNP) and Pre-School Education (PSE) has been falling over the years. Between March 2014 and January 2019, the number of children (6 months – 6 years) receiving SNP fell by 17 per cent from 849 lakh to 705 lakh. Similarly, between March 2014 and January 2019, there was a decline of 14 percent in number of children availing PSE.

This is where we stand with respect to Aganwadi centers. On the other side, government primary schools have been hollowed out and large number of them have dropped to below 50 children enrolled. They are being closed or merged. There are newspaper reports that 13000 schools in MP where enrollment is below twenty are going to be closed and students merged with other schools. This is the current social context. The NEP document wrongly suggests that the expansion of public system created this small school scenario. This is the result of allowing small private schools to mushroom. By not improving the administration and investment in public system the government encouraged exit of children from government schools on a wide scale. Unless there’s a bringing back of public trust and functioning of government primary schools making this change in structure would be like adding an extra bogie to a consciously derailed train.

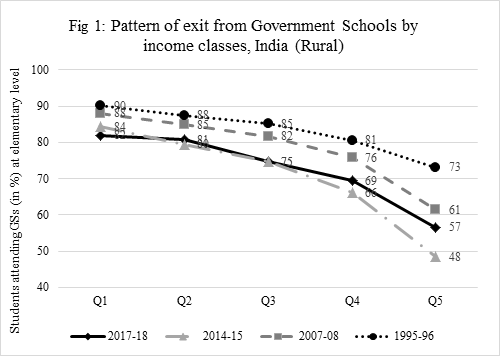

Examine the following data for rural areas from a larger study.

“Fig 1 plots the proportion of children in GSs at the elementary level in each income class (defined in terms of five consumption quintiles) across four National Sample Survey (NSS) rounds on educational participation in India. Each line corresponds to a particular time point, whereas the different quintiles are represented along the line. The downward movement of the curve over the years indicates the extent of exit. For rural India, the share of children in GSs for quintiles 4 and 5 have declined by 12 and 16 percentage, respectively, between 1995-6 and 2017-18. Further, as the dominant classes exit the GSs, the lowest quintiles have followed suit. Still, more than 80% of the children attending school from the lowest income groups are in GSs.” (Bose, Ghosh & Sardana: Exit at the bottom of the Pyramid, WP, NIPFP)

What is likely to happen and is already taking shape is that all small low fee private schools in rural and semi-urban areas have added on a preschool component. They are already implementing the suggested policy? No. They are turning the policy on its head. The preschool education in these private schools goes against all accepted principles of ECCE since they compete with each other to show how children in their schools could be forced to quickly learn the alphabets and be able to write them; learn and recite some tasks that could be showcased. These children also learn to disregard the home language and culture with the focus on snippets from the dominant language. The practice here is totally contrary to what is suggested by the policy document but they have the structure of preschool in place. Hence what is likely to be implemented is the very opposite of what is being suggested- the expansion of small low fee private schools and practice that is contrary to the objectives of early childhood education.

The policy framers know this. Why then is this conflict not discussed? Is the intention to let privatization flow by looking the other way? A policy document is expected to present an analysis and outline pathways in difficult socio-cultural conditions such as improving and investing in government primary schools. If it doesn’t examine the impediments in the process then this is like repeating ‘mantras’ in the hope that good sense will somehow prevail.

Let us examine another big idea, that of change in the format for Board examinations. NEP says that they will move away from testing rote to more conceptual and applied questions that allow for creativity & critical thought. This has been an objective for decades but we appear to be in the same place like ‘Alice in wonderland’. Our classroom culture reflects the expectations of these tests where guides, important questions, speed and recall of information are emphasized. Much has been written on this.

Board examinations have become de facto entrance tests for colleges and there is the unethical competition among them to inflate marks for the advantage of their students.

On paper it is logical and appropriate to separate The National Assessment Center for School Education and the National Testing Agency. They have different roles. The purpose of the first is to focus on overall learning and certify competency; the purpose of the second is to focus narrowly on the subject, to select and reject. It works with a mix everywhere but in our situation where there are lakhs of aspirants and few decent formal jobs available, schools and the market totally disregard this difference. And will continue to do so. The dominant paradigm is of the testing agencies and entrance examination. This has now led to coaching agencies for these tests to run schools. If the market has dissolved the difference between a coaching center and a school, we can’t sweep this reality under pious intentions. This is the dummy school model, widely practiced today. In these schools run by coaching institutes the main focus are the entrance tests while Board preparations are treated like a dummy objective to be got over with in a cursory manner.

The honest thing again would to acknowledge the difficult social situation and why these two different roles would be largely unacceptable. If you were to prune the syllabus for the Board but leave the syllabus for these tests extensive it would not work. The syllabus for the test and its assessment methods would be the de facto curriculum and classroom pedagogy. If you were to change the formats and syllabus of the entrance tests it would produce strong reactions from entrenched interests. Many of them are convinced that these national tests are the best way to identify merit. They downplay the role of cultural resources that help some & the fact that the coaching industry is successful in cracking what is required. There are no easy answers but you have to face a storm if you are seeking change. The NEP ducks this question and we may still be running faster and faster to be in the same place. (Sardana)

Examine a third idea, vocational training for all. We live in a situation where formal jobs are desired by lakhs but only a few can find one. And for this, as emphasized above, college education is required and therefore clearing the barrier of entrance tests become all important. For the rest it is the informal sector. To be clear on the overall situation examine the following:

“In 2018–19, the most recent year for which for the labour force data is available, 52% of the workforce were classified as self-employed. Over 95% of the self-employed were either own account workers (i.e., those who operate enterprises without hired labour) or unpaid family workers. Less than 5% of the self-employed were classified as employers (i.e., those who operated enterprises with hired labour).

Approximately 24% of the workforce were employed as casual workers with no stability of income or security of tenure. And like the self-employed, they too were outside the ambit of employer-employee relationships that offered employment-linked benefits.

Regular wage salaried (RWS) workers constituted the remaining 24% of the workforce. These workers received a salary on a regular basis and not on the basis of daily or periodic renewal of work contract. This made them better off than casual workers, but not all of them had access to social security benefits or secure job contracts.” (Radhicka Kapoor)

This is where we live. Most of our students are likely to become part of self-employed and casual workers but their valid aspirational desires are for regular wage salary. And why not? Schools present a small ray of hope. The wrong turn the NEP takes considering this situation is to introduce vocational training for all from middle school onwards. It says that some vocational training for all will remove the stigma. It will work the other way around. Pure Vocational training students would be in section C at school or some group of schools would be designated for vocational education. This would lead to institutionalization of the stigma.

Combined with caste, gender or tribal background this would be greatly regressive. It would be understood as being trained for low paid insecure self-employed jobs of the informal sector or agriculture. Their opportunity to join the ranks of regular salary workers would be cut off at middle school. This is not striving for equality of opportunity and goes against the constitutional ideal.

Instead for class 6-10, where formal subjects are introduced there has been a half-hearted attempt to work with your hands. This is pedagogically good for all. This implies doing hands on science, genuine project work by children, local surveys, craft skills, music etc. Every school has ample opportunities to use local resources. Since this is never made part of assessment it doesn’t get done, even when textbooks incorporate such activities. None of the entrance tests look at these skills and aptitudes. Not working with your hands is a caste attitudinal barrier, deeply ingrained in our society. Allowing all children this experience is both good pedagogy and sensible social policy. This would be a relevant aim not vocational education for all at this level. Vocational education streaming could come later at higher secondary level.

Let us examine a regressive idea not usually commented upon but likely to be pushed. This is to start ECCE for ashramshalas, residential tribal schools run by the Tribal Welfare Department of the state government, supported by central grants. The problem is not with ECCE but with residential primary schools. Residential schools should not begin at the primary level. These children should be with their families imbibing home culture & love and support. Alienation for tribal children in residential schools have been observed by researchers, the world over.

Children need to attend local schools. Unlike in the past, the schooling infrastructure by state governments has made deep inroads and they provide access today. Whenever there’s a move to remove primary sections from residential ashramshalas and allow them to study at the state run local primary schools, this is opposed by vested sections. There’s also a turf battle between departments. This step of introducing ECCE will make primary sections at ashramshalas more entrenched and difficult to dislodge.

It is not possible to cover all the ideas of the document. However, if you look under the rhetoric many progressive sounding ideas would not be implemented in its spirit and practice is likely to go in the opposite direction to what is intended.

- Examine the issues where the document is silent or makes a cursory mention

The first issue is that of RTE. There’s a vision of universalization and equity in this Act. Whatever it drawbacks it needs to be examined upfront since we have a decade of experience of its implementation or non-implementation.

One point of view would say that the Act is not being implemented since there’s no financial plan backing it up nor is there the political will to enhance the quality of administration of our public schools and to seek the collective participation of teachers. The other view as hinted by the NEP is that the Act is ‘restrictive’. The comprehensive list of requirements for a school as listed in the schedule of the RTE Act can’t be reasonable fulfilled by small private schools that now are a major segment of the schools in urban & rural areas. Schools that charge Rs 300-800 as fees can never be close to the salary expectations of a decent job nor can they fulfill infrastructure requirements of playgrounds, classroom quality, library and labs. If school supply is to be increased by private resources in a bigger way then these norms should be diluted in the Act and in the rules framed by state governments. Schools should not be compelled to seek illegal methods to fulfil these restrictive conditions. Today at least 20% of children are at schools that could be de recognized if RTE is implemented in spirit. This is a huge number. There are two routes. Dilute the rules and legitimize these schools & encourage more of the same. The other route is to implement RTE, increase public supply & public trust of government schools. Derecognize those that don’t fulfill the minimum conditions. We need to face this dilemma now and the document is silent. Are we heading towards a fait accompli situation?

The other issue is the budget for education. When 6% of GDP is repeated without any details of financial planning and assurance of provision, it rings really hollow. It would be done subsequently doesn’t add faith. We are repeating this target from 1968 onwards. Independent estimates (Bose, Ghosh& Sardana) using U DISE data for 15-16 show that we require an additional expenditure of 1.2 % of GDP (15-16) to implement RTE with reasonable norms. This would still be under 6% but a substantial increase in allocation. A sizable section of the bureaucracy and political class have expressed the inability to administer large public systems and regularly claim in private that this is waste of expenditure. It is time to confront this view. The document’s silences appear to support privatization to happen by stealth. It seeks to present the state as being helpless in the face of public exit from government schools. This requires an open political debate and not decisions taken by stealth.There are clever omissions and change of emphasis. NEP doesn’t mention secularism but counters this by talking of pluralism, as if the meanings are the same. This is clear ideological posturing.These debates on democracy, secularism will play out once the NCF is announced and guidelines for textbooks laid out. We may be back to the stage where political analysis is dropped and textbooks go back to repeating the bare constitutional text and listing rules. What is however clear is that analysis of marginalization processes whether for SC or ST or for women is going to be sidelined. Constitutional provisions, reports of various committees or scholarly analysis regarding the influence of caste, class or gender have been made irrelevant by lumping all as SEDG. This is a very much market inspired category. It is often used to group people who ‘unintentionally’ get left behind in the market process and therefore require safety nets. This categorization would ignore that the reasons that are structural or that marginalization is reproduced through social categories. The categorization of SEDG suggests that is a small unfortunate group in the process of development. It clearly ignores that this group would constitute 70% of the population.We should imagine the NEP as a distillation process through the political chamber. The draft NEP has been dropped and with it the promise of many progressive ideas. We now have the NEP. This too with its suggestions of flexibility and a liberal view of education would soon be kept out. What would be implemented would be cherry picked schemes. This is already being done with funding for aspirational districts and wide spread roll out for assessment test mechanism at all levels. We could see Centrally Sponsored Schemes for ICDS & for areas selected as educationally disadvantaged that need to be patronized. States who have the main operational responsibilities for mass education would be squeezed for resources. We are likely to see an expansion in the private sector at two ends. One there would be another surge in the CBSE schools across states such that the aspirational groups everywhere are aligned to the uniform national curriculum & the testing mechanism for college admission. At the other end small private schools would be made legitimate and pushed as the main vehicle for universalization process, within the state.

- Where does hope lie?

At one level it is clear that the initiative to interpret and modify the NEP would have to come from the states. They are the main operational actors and also provide substantial funds from their meagre sources. They need to demand more resources for education through greater allocation via the Finance Commission. In our estimates sixteen states require substantial financial support if there are to fulfill their obligation under the RTE Act. (See Bose, Ghosh & Sardana)They also need to set their own priorities towards equal education for all and politically project this as a feasible operational plan. How political parties at the state level think and act would determine the track for NEP. This will be varied but how they articulate and negotiate with the center would determine the opportunities for the non-elite in their state.

The other sign of hope are the discussions among many groups and hopefully they would draw up some action points. These could be demands for regulation of private schools in the atmosphere where fee hikes are pinching everyone and exposing the naked exploitation of parents. In a situation of economic distress the fall back on government schools is real. This small trickle if built upon could lead to some resurgence and enhanced public trust for government schools. It is not happening now but it could be dreamt about. May be different ways of organizing and placing the centrality of health & education in today’s context. Pursuing action through courts using PILs has been a valid route but this appears to have reached a plateau. This is not to be given up otherwise the ideal of quality education for all would be reset. The reasons for this is the fatigue of the courts with regard to PIL and the view that they can’t be always correcting the governance deficit. All private schools are operated through valid trusts but behind the veil a large section are for-profit entities. (See Report of the Justice Anil Dev Singh Committee)The number of children in such schools is large and courts would be vary of banning these entities when there appears to be no public effort to increase supply. Between the devil and the deep blue sea they would be tight lipped.

Arvind Sardana has been a member of the Social Science Team at Eklavya and has been associated with textbook development teams at NCERT and with other state governments such as Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Telangana.

I would like to thank Ram Murthy Sharma for extended conversations and sharing space for the webinars on NEP. Also grateful to colleagues at Eklavya, teachers and friends for their questions during these sessions. Needless to add, views expressed are personal.

– Arvind Sardana