COMMENTARY

Shehla Rashid’s decision of adorning a Hijab at Shah Faesal’s party launch reminds us of identity politics and the vulnerability of sartorial preferences, in our times.

Kavya Thomas | The New Leam

Shehla Rashid’s rise to prominence during the protests that took place at the Jawaharlal Nehru University Campus in the aftermath of the arrest of the then JNUSU President Kanhiaya Kumar and union members Umar Khalid and Anirban Bhattacharya in February 2016- epitomized the birth and emergence of a new, politically sharp and active voice that would make its presence felt on India’s political map in the subsequent months.

Shehla Rashid Shora is a woman, a Muslim and hails from the state of Jammu and Kashmir- a triadic combination of minority identities made her an even more important voice to reckon with. Perhaps that is why every tweet, every Facebook post, every speech and every public appearance that Shehla Rashid makes is scrutinized by the media and discussed, often under the veil of controversy.

From death threats to rape threats, from abusive trolling and sexist attacks to being told to go to Pakistan and settle down there- Shehla Rashid has been as much a victim of her unique and politically complex identity that she has as a woman, a Muslim and a Kashmiri as much as the attention that she has received on its pretext.

The recent controversy that rose around her was related to her decision of covering her head in a traditional Muslim scarf or a Hijab for the launch ceremony of former IAS officer Shah Faesal’s party in Srinagar. She has been deeply involved with Faesal’s Jammu and Kashmir Peoples Movement for some time and this is seen by political analysts as her stepping ground into full time politics.

The act of covering her head for the function in a traditional Islamic headscarf or Hijab became the centre of much controversy because it clearly appeared to be in stark opposition to Shehla’s public image as a radical feminist and an advocate of Leftist politics.

For someone who had so openly spoken about oppressive patriarchy, the need to debunk archaic religious practices that denied women’s dignity and talked about gender equity and women’s liberation- the act of adorning a Hijab didn’t appear quite in sync.

The trolls that raised objections over Shehla’s choice of headgear and raised questions on the authenticity of her feminism received a solid response from Shehla when she said that the reason behind the trolls was her gender.

She articulated the fact that because she was a woman, people chose to comment on her sartorial decisions but had she been a male politician (she referred to Prime Minister Narendra Moddi’s adornment of a wide range of headgears at various public rallies and yet never being questioned about his choices) her sartorial sense would hardly have mattered.

With nearly 5 lakh followers on Twitter and a constant array of critical observations on the Narendra Modi government, every post that Shehla Rashid puts on the internet raises new controversy.

Was the decision to cover her head for the function regressive? Can Shehla Rashid’s choice of adorning a traditional, religious symbol be forgiven because her politics is radical?

For someone who has often called religion the opium of the masses, in tune with the Marxian axiom and time and again asserted her commitment to radical feminism, how must one look at her choice of accepting a veil (a supposed onslaught on women’s freedom and access to public life)?

Shehla Rashid says that her acceptance of the headscarf should not be seen as regressive because her political choices continue to be progressive. Moreover, she asserts that because she wants to involve the Kashmiri women in the mainstream politics in the state, her choice of the headscarf is only to make herself more relatable to them.

She says that politicians have always made an attempt to dress up in ways that attract the least public attention and make them appear in sync with the wider population; their sartorial choices can make them appear both relatable and distant.

Did the Modi government remind Shehla Rashid that she was a Muslim- an identity that perhaps lay dormant behind the more politically visible ideological choices such as that of being a Marxist/ Leftist and a feminist?

We find ourselves at a historical juncture when sustained attacks on the Muslim community have made them feel threatened, insecure and compelled to readopt their cultural symbols as if in an unprecedented sense of self-defence.

Thus given the political climate, Shehla Rashid’s choice of wearing a Hijab is both political as well as strategic. Even when she claims that she is no votary of identity politics, her sartorial choice certainly sends across a strong political message to all the Muslims in general and to the Kashmiris to be specific.

Shehla Rashid may have studied in JNU, may have been known for her fierce Marxism and radical feminism, she may have been seen as a student leader who has spoken vehemently on the injustices met out to the lower castes as a staunch Ambedkarite but her choice of cladding her head in a Hijab has reminded us that she is today using her own cultural identity as part of her politics.

A libertarian politics that is truly radical demands us to vehemently critique all sources of oppression (whatever their origins may be) and strive towards a political arrangement that is non-discriminatory, egalitarian and premised on justice.

For such a politics, the non-entry of menstruating women into the Sabarimala Temple on the pretext of ritual impurity, the attacks on Hindu women for dowries and female infanticide due to the obsession with a male child, the practice of compulsively covering the faces of new brides in many Hindu households, the presence of discriminatory inheritance and property laws, the indignity of Hindu women in real life irrespective of the fact that they have been given divine status in scriptures should be as much a problem as is the custom of Triple Talaq or the compulsive Burkha and Hijab. How can one form of oppression be seen as less faulty than another, how can the movement for women’s liberation be limited to the subscribers of only one religion?

The question that we must ask Shehla Rashid is not whether her intention behind wearing the Hijab was to only bring about compatibility with her Muslim women but whether she will be willing to look at the sartorial preferences of other political activists such as a Swami Agnivesh with the same rationality?

Swami Agnivesh adorns a saffron robe (the quintessential attire of a Hindu mystic) but does not practice hierarchical Brahmanism or feudal patriarchy but works against bonded labour since 1981. He has served as the Chairperson of the United Nations Voluntary Trust Fund.

Is Shehla Rashid prepared to look at him beyond his dressing preferences?

What about a social reformer like Pandita Ramabai who happened to be an upper caste woman but gave her life to the movement for women’s liberation in India? She wrote against the oppression felt by Hindu upper caste women in her book The High-Caste Indian Woman. Why do feminists like Shehla Rashid not take her name when they talk of the feminist movement in India? Do they not make the mistake of limiting Ramabai into her Hindu, upper-caste identity? If Shehla Rashid is expecting us to see her beyond her Hijab, why can’t Ramabai be seen beyond her caste?

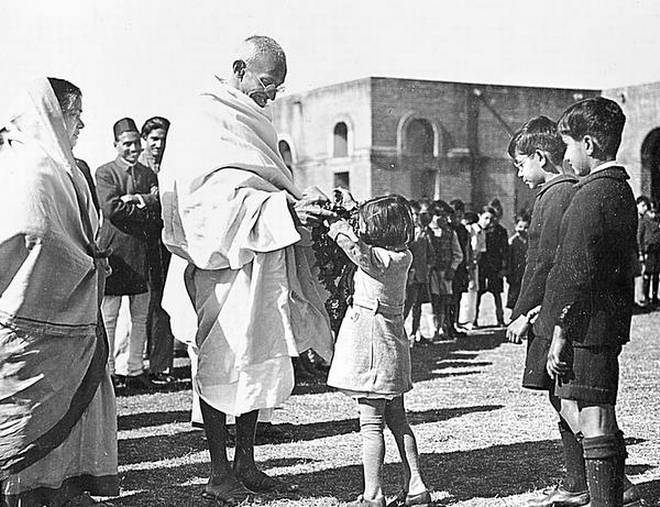

What about a man like Gandhi? To relate to the wide masses in India, Gandhi used a wide range of terms which he drew from Hinduism such as the concepts of ahimsa (non-violence), satya(truth), Harijan, Ram Rajya among others.

Does his vocabulary limit him to being just a Hindu?

Or do we look at his work with the untouchables, the farmers and peasants, the downtrodden and the oppressed in order to understand his brand of politics?

If Shehla Rashid urges us to see her sudden adornment of a Hijab as not a regressive choice but one made in order to become relatable for her political audience, if she demands that we consider not her clothes but her political choices- she must be ready to give the same freedom to many political leaders and activists who have adorned symbols of culture or religion without necessarily being limited by them.

After all, a partial radicalism and an opportunist utilisation of religious symbols cannot take us very far, if we as a nation don’t learn to ask for leaders who represent the collective called India and not its bifurcated fractions.