Here is a young political theorist gifted with the power of observation and art of critical thinking. At a time when we see all sorts of violence and totalitarian tendencies in the name of nationalism, his creatively nuanced engagement with Gandhi, Nehru, Ambedkar and Tagore is immensely promising. With deep insights into philosophy and politics, and sociology and literature, Dr. Bhattacharjee has offered us a wonderful book. Hers is an excerpt from the book for our readers.

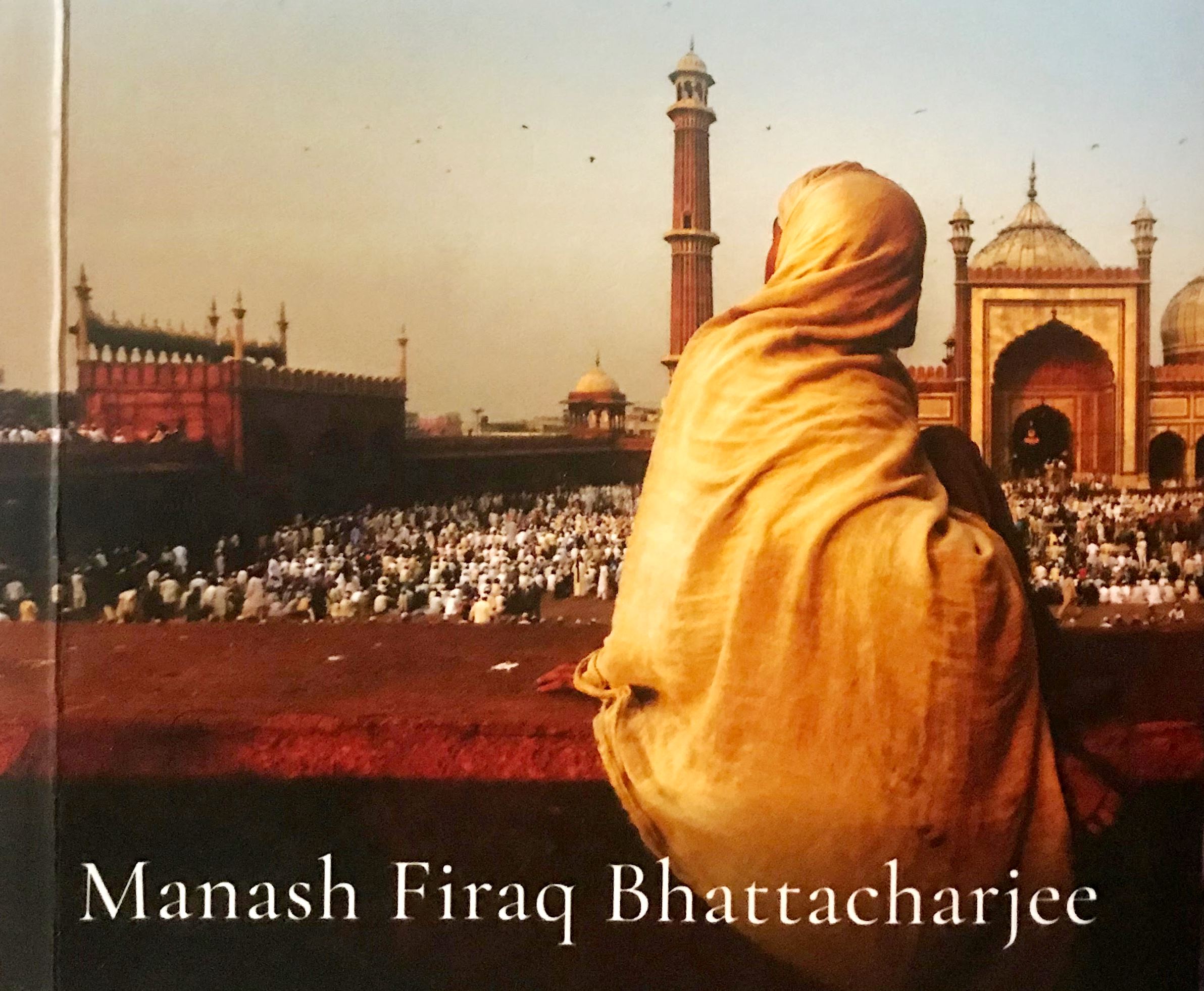

Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee

Nationalism, now reduced to hunting for enemies who think differently, is the enemy of thought. Fascist politics fears the sovereignty of thinking, and aims to subordinate it through violence. Fascism is pure, thoughtless violence, in search of a pure racial (and casteist) body. It is the violence of body over mind, the claims of a body trying to retain its purity against a mind that has been corrupted and contaminated by the outsider. Fascism seeks the most fortified territory of the self, where the original violence of a community is restored. The enemy alone gives life to fascism, which is consumed by its own obsession with death. It suffers, and makes others suffer, for an abstract idea of a lost community or nation that was originally perfect, illustrious and beautiful. Before the enemy entered their territory and spoiled it. In fascism, life and death are real questions, but the idea of suffering is abstract. This is where fascism differs crucially from religion, where the question of suffering is real and immediate. While the primary question of progressive political thought is not different from that of religion-i.e. how to address the problem of suffering–it is also trapped by the idea of war against the (class) enemy.

The task of our era is perhaps to think beyond the idea of the enemy.

This is the promise of ethical thinking. Ethics is thinking without the enemy, which by itself breaks the frontiers of territorial thought, and imagines a common ground of meeting and dwelling wherein, the enemy is the (potential) neighbour. Ethics is difficult politics, and it is the unique distinction of the Indian nationalist movement, that men like Gandhi, Ambedkar, and even Nehru, thought in nonviolent terms of resolving the political crisis with the British, as much as the problems within Indian society, through nonviolent methods. They were constantly able to think (and write) despite their various political engagements, only because they took the activity of thought seriously. In this sense, the Indian nationalist movement had a strong ethical streak. Thinking resists power nonviolently, for it has not given up the promise of response.

The banal argument often made that Gandhi’s nonviolent movement would have failed against Hitler, proves two things: one, that the Gandhian movement is relevant against all other forms of power, and two, that fascism is the most dangerous enemy of all ethical struggles against power. Fascism doesn’t understand ethics, because it cannot exist without violence. In Ambedkar drinking water from the tank at Mahad in 1927, and Gandhi walking the lanes of Noakhali in 1946, barefoot, are two powerful yet endearing images. In life as in politics, the most inspiring acts of courage are simultaneously a risk of one’s vulnerability.

SOURCE: Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee, Looking for the Nation: Towards Another Idea of India, Speaking Tiger, New Delhi, 2018