TRIBUTE

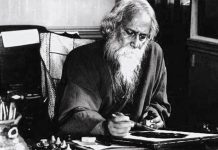

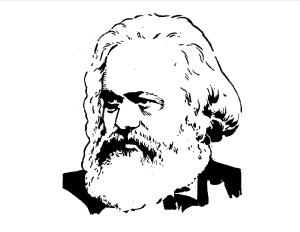

Karl Marx was born on May 5, 1818; and Rabindranath Tagore on May 7, 1861. Marx showed us the power of critical consciousness, a methodology to look at history and its contradictions, and an aspiration for a new society free from exploitation, alienation and fragmentation.

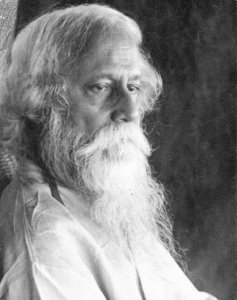

And Tagore was a poet who helped us to overcome the growing disenchantment, realize our innate beauty and creativity, and experience the grace of profound religiosity as a merger with the divine.

Here we recall Marx’s reflections on commodity fetishism—the way human relations get transformed into relations between two objects because of the very logic of exchange of commodities in a capitalist economy.

And at the same time, we recall Tagore’s prayer, his divine longing, his religiosity. An emancipatory philosophy, we believe, needs both—a revolutionary as well as a poet.

A commodity is therefore a mysterious thing, simply because in it the social character of men’s labour appears to them as an objective character stamped upon the product of that labour; because the relation of the producers to the sum total of their own labour is presented to them as a social relation , existing not between themselves, but between the products of their labour. This is the reason why the products of labour become commodities, social things whose ualities are at the same time perceptible and imperceptible by the senses. In the same way the light from an object is perceived by us not as the subjective excitation of our optic nerve, but as the objective form of something outside the eye itself. But, in the act of seeing, there is at all events, an actual passage of light from one thing to another, from the external object to the eye. There is a physical relation between physical things. But it is different with commodities. There, the existence of the things ua commodities, and the value-relation between the products of labour which stamps them as commodities, have absolutely no connection with their physical properties and with the material relations arising therefrom. There it is a definite social relation between men that assumes, in their eyes, the fantastic form of a relation between things. …This I call the Fetishism which attaches itself to the products of labour, so soon as they are produced as commodities, and which is therefore inseparable from the production of commodities.

— Karl Marx, Capital, Volume 1

(II) You are to Attain the Impossible, You are Immortal

This great world, where it is a creation, an expression of the infinite—where its morning sings of joy to the newly awakened life, and its evening stars sing to the traveller, weary and worn, of the triumph of life in a new birth across death,–has its call for us. The call has ever roused the creator in man, and urged him to reveal the truth, to reveal the Infinite in himself. It is ever claiming from us, in our own creations, co-operation with God, reminding us of our divine nature, which finds itself in freedom of spirit. Our society exists to remind us, through its various voices, that the ultimate truth in man is not in his intellect or his possessions; it is in his illumination of mind, in his extension of sympathy across all barriers of caste and colour; in his recognition of the world, not merely as a storehouse of power, but as a habitation of man’s spirit, with its eternal music of beauty and its inner light of the divine presence.

— Rabindranath Tagore, ‘The Poet’s Religion’