As the great and good of the movie world get ready to step out on the Oscars red carpet, old Hollywood glamour – and old Hollywood values – remain central to the night. The Academy Awards presentation is one of the most prestigious events in the film industry. And while the awards are the focus of limited academic research, they offer insight into Hollywood trends and the issues faced by the American film industry.

By assessing the Oscars’ current status, we can clearly see tension arising between the old guard of Hollywood and the newer values and practices of the industry. Debates around the diversity of nominees – both in terms of gender and race – come at a time when the way that we interact with film is changing.

Online streaming services are offering easy access to movies. And although some streaming firms’ films have been recognised by the Academy Awards, movies are only eligible for nomination if they have had a theatrical release alongside their online debut.

In 2019, Alfonso Cuaron’s Roma became the first Netflix film to be nominated for best picture. In 2020, an even more extensive slate of Netflix movies have been nominated for a total of 24 awards, including The Irishman (four including best actor, best picture and best director), The Two Popes (best actor, best supporting actor and best adapted screenplay) and Marriage Story (six including acting, directing and screenplay).

But despite Netflix’s seeming dominance of this year’s Oscars, the relationship between streaming services and the Academy has not been without controversy. Martin Scorsese has begged people not to watch The Irishman on a phone screen. This seems odd coming from a director who is clearly benefiting from a service that offers its subscribers the ability to watch films anytime, anywhere.

In 2019 Steven Spielberg spoke in favour of the Academy only celebrating films that have had a theatrical release and one of the prize’s key rules is that a film must have a “qualifying theatrical run of at least seven consecutive days, during which period screenings must occur at least three times daily”.

At least one of these screenings must be between 6pm and 10pm in the evening and the theatrical run must be for “paid admission in a commercial motion picture theatre in Los Angeles County”. This is a potentially prohibitive rule for smaller-scale or streaming service-only productions. It also underlines the old-fashioned idea of LA being the one and only home of movies.

New tensions, old values

The Academy’s difficulty in keeping up with the times is also evident in the regular rows over diversity. Claims of sexism and racism, as well as ageism and homophobia, are frequently levelled at the Academy Awards. In 2012, a study by the LA Times found that 94% of Oscar voters were white and 77% were male.

The Academy has attempted to improve these figures in recent years, breaking its own cap of 5,000 members in order to diversify its voters. A recent report revealed that the Academy had issued more than 900 invitations for extra voters as part of a diversity initiative in 2018. Nearly half (49%) of those invited were female and 38% were people of colour. Beyond that, however, the make-up of the Academy’s membership remains opaque.

Despite the push to improve the diversity of the Academy, the lack of women nominated for best director has become a tiresome norm for the Oscars – and 2020 is no exception. Likewise best actor and supporting actor nominees are all white, as are best supporting actress. In the best director category, only the presence of Bong Joon Ho for Korean movie Parasite mitigates against the once again deserved hashtag #OscarsSoWhite, while Cynthia Erivo is the lone woman of colour vying for best actress.

Such biases are exacerbated by the regulations regarding theatrical release. Streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon Prime offer opportunities to women and filmmakers of colour that are not available in the mainstream but these films tend to be overlooked at awards ceremonies.

For example, Lynne Ramsay’s 2017 film You Were Never Really Here, a film distributed by Amazon, was hailed by critics but failed to receive a single nomination for the 2018 Oscars. Meanwhile directors such as Scorsese – whose names can justify the brief theatrical release required by the rules and who bring “prestige” (not to mention lots of viewers) to these services – tend to overshadow the less well-known names.

I’ll catch it on Twitter

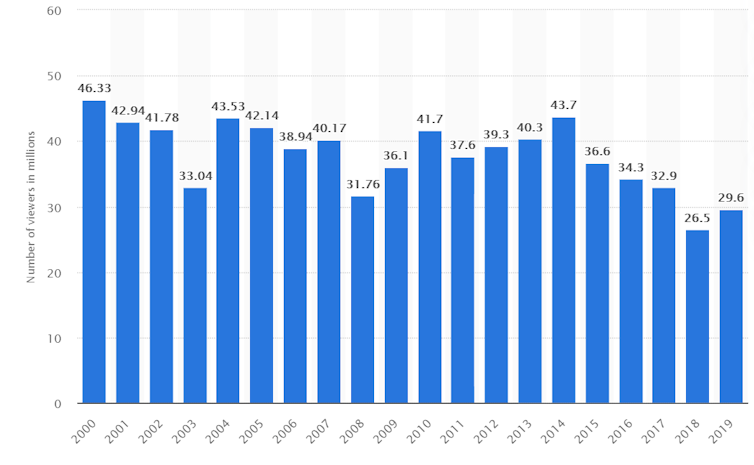

Perhaps as a result of this, there’s been a downturn in interest in the Oscars broadcast in recent years. The 2018 and 2019 Academy Awards achieved the lowest ratings ever for the ceremony.

© Statista 2020

Critics believe the Oscars have become increasingly predictable in terms of who wins awards. The long speeches and problematic hosts have also become offputting for viewers. Seth McFarlane’s sexist performance of We Saw Your Boobs at the 2013 ceremony was widely criticised as distasteful and, in 2019, the awards ceremony was without a host after Kevin Hart stepped down following controversy around his homophobic humour and offensive tweets.

The broadcast is also struggling to adapt to changing viewing practices of both the ceremony and the films it highlights. While ratings for the televised ceremony fall, key events or scandals (remember when Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway announced the wrong winner of best picture in 2017) are becoming the key talking points in the hours after the ceremony and tend to be consumed as clips via social media or YouTube.

These viral Oscars “snippets” – and their evident popularity – suggest that today’s audiences are less interested in the prolonged celebration of traditional Hollywood and are more likely to want to pick and choose what aspects they engage with. So, if the way in which we interact with film is changing, can the Academy keep up?![]()

Claire Jenkins, Lecturer in Film and Television Studies, University of Leicester and Stevie Marsden, Research Associate, CAMEo Research Institute for Cultural and Media Economies, University of Leicester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.