ECONOMIC INEQUALITY

Growing economic inequality seems to be tearing the world apart. The disparity has resulted in undignified lives, unemployment and the absence of even the basic necessities for a large section of the population.

Nivedita Dwivedi is an Independent Writer. She is working in the field of education and—based in Mumbai.

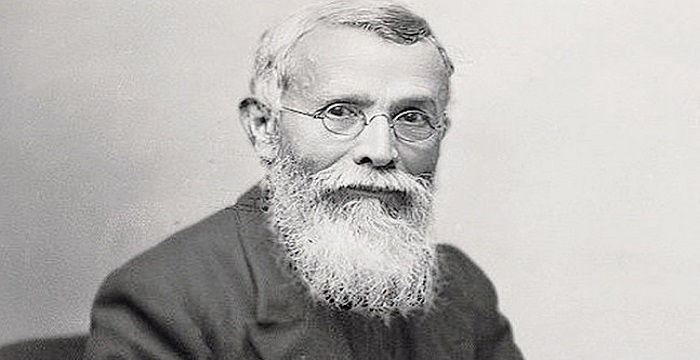

Dadabhai Naoroji’s book, ‘Poverty and Un-British Rule in India’, was published in 1902, more than a century ago. His work highlighted the ‘Drain of wealth’ theory, wherein he was primarily trying to establish how British rule was leading to constant pauperization of the Indian nation. Naoroji listed down six factors, which he felt were responsible for the drain of wealth from India, resulting in widespread poverty in the nation.

Firstly, that India was governed by a foreign nation. Secondly, India did-not attract immigrants which brought labour and capital for economic growth. Thirdly, India paid for British civil administration and occupational army. Fourthly, India bore the burden of empire building in and outside of its borders. Fifthly, opening the country to free trade was actually a way to exploit India by offering high paid jobs to foreign personnel. And lastly, the principal income earners bought outside India or left with the money as they were mostly foreign personnel.

For the time being, let us leave the above analysis as it is and fast forward to the present times. In order to understand poverty better, it is important to first define it. Unfortunately, it has not been possible for this entire world, in so many years, to arrive at a universal definition of poverty. First and foremost, just to clarify, poverty, when used in general terms, refers to economic poverty, and this is what the world has chosen to focus on, discuss and define. Secondly, world-over and in India, economic poverty is defined in terms of how it is measured. Various estimates are used to calculate the number of people living below a certain income per day. That level of income is defined as the poverty line and the people having an income below that number are officially defined as poor.

Let us have a look at some of these numbers. According to the Modified Mixed Reference Period concept proposed by World Bank in 2015, India’s poverty rate for period 2011-12 stood at 12.4% of the total population, or about 172 million people, taking the revised poverty line at $1.90 a day. Let us now have a look at another poverty estimate, again suggested by the World Bank. From November 2017, the World Bank started reporting poverty rates for all countries using two new international poverty lines: a “lower middle-income” line set at $3.20 per day and an “upper middle-income” line set at $5.50 per day.

India falls in the lower middle-income category. Using the $3.20 per day poverty line, the percentage of the population living in poverty in India was 60% (2011). This means that 763 million people in India were living below this poverty line in 2011.

All such estimates are just numbers, informing us about the number of people that may be earning less than a specified income. That specified income varies with different methodologies and for some reasons is used to distinguish between the poor and those that may not be called so. But let us just try to put things in perspective for ourselves. In 2015, according to United Nation’s Millennium Development Goals (MDG) program, India has already achieved the target of reducing poverty by half, with 24.7% of its 1.2 billion people in 2011 living below the poverty line or having income of less than $1.25 a day, the U.N. report said. The same figure was 49.4% in 1994. India had set a target of 23.9% to be achieved in 2015.

According to a different kind of estimate, i.e., according to Global Wealth Report 2016 compiled by Credit Suisse Research Institute, India is the second most unequal country in the world with the top one per cent of the population owning 58% of the total wealth.

The comparison between the two different estimates provided in the previous paragraph, provides for me, the crux of the entire poverty issue, not only in India, but the world over. And the crux is that even though the percentage of people, ostensibly defined as poor may be reducing, the inequalities in wealth are increasing at such levels that it sounds obscene, to say the least.

Within the structures and arrangements of the present-day world, where development is defined in predominantly economic terms, the one measure which is quoted when discussing a country’s development is GDP (Gross Domestic Product). GDP is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced in a period of time, often annually or quarterly. In the recent times, India has consistently been ranking as one of the fastest growing economies in terms of GDP growth. Contrast this with the estimate provided by the Global Wealth Report 2016, which says that India is the second most unequal country in the world. This goes on to indicate that the so-called growth that India has been clocking has been feeding the growing income inequalities in the nation.

In other words, once an individual crosses a certain number which the world defines as the poverty line, he/she cannot even be called poor officially. It means that the world feels that bare minimum sustenance in this world is enough for some people whereas for some others, even sky need not be the limit. The world today does not find even an iota of injustice in the fact that the richest 1% may corner the majority of its wealth leaving the vast majority scampering for the remains.

Dadabhai Naoroji had attempted to provide reasons for poverty in the context of the British rule. More than a century later, today, when colonialism has changed its nature from overt to covert, is there something that has changed? How can the six factors that he listed be viewed in today’s times?

The first reason to which he attributed India’s poverty was that she was ruled by a foreign nation. While she may not be today, however, the structures by which India or the entire world is ruled today are as much foreign to the idea of humanity as they can be. These are the structures which promote inequalities and refuse to treat majority of the human beings inhabiting this earth as even humans.

Secondly, he felt that India did not attract immigrants, who could bring in labour and capital. If we talk only in terms of external migration, migrants who could bring in capital may still be wary of India as a destination, because of its ever-persisting internal issues, whereas immigrants in terms of labor are actively discouraged in today’s worlds where the idea of physical boundaries is being increasingly interpreted in narrower terms.

Thirdly, at that time India may be paying for the civil and military administration of a colonial power, whereas today the majority are paying for a miniscule minority’s ostentatious riches and for the indiscretions of the corrupt political-bureaucratic-business nexus.

Fourthly, whereas India bore the burden of empire building in and outside of its borders then, today India is bearing the burden of empire building by its politicians and business-people within the nation.

Fifthly, while at the time opening the country to free trade could be actually a way to exploit India by offering high paid jobs to foreign personnel, today free trade is regarded as a non-negotiable component of the new world order.

And lastly, whereas at the time the principal income earners may have bought outside India or left with the money as they were mostly foreign personnel, in the revised world order where multi-nationals are the order of the day, this factor becomes largely redundant.

So, what has changed over the course of an entire century? Only this that the space for the poor has shrunk even further and no boundaries bind the rich of the world. The world, instead of coming closer is expanding in two opposite directions, tearing apart the entire fabric of a civilized society. Is there any end in sight to this madness? At least to me, it does-not appear to be.