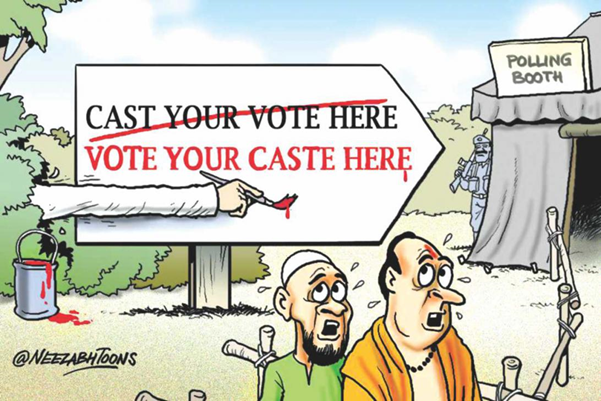

I don’t wish to write a note on the sociology of caste, which I think deserves a lot more space and work than what I am doing here, neither is this a note simply describing the politics of caste. I wish to address something specific in this note concerning a certain discourse on caste that is emerging; it is suppressed but is gradually becoming stronger in its own silence. The discourse is represented by this line of thought: ‘BJP is uniting castes under one umbrella’, the other side of this discourse being that ‘this unity is being achieved by the othering of Muslims, the common threat against which this unity finds its structural orientation’.

The real threat of a discourse like this doesn’t come from its overt support, which of course in one form or another the right-wing groups articulate, but the unsaid inertia to such beliefs that is built-up by the silences in the dominant discourse. It’s almost as if any confrontation with the current realities of Indian politics will take us to beliefs in the vicinity of the above statements. Our orientation towards nationalism, secularism, our idea of India, all are somewhere stuck in the paradox such a choice is throwing at us. I just wish to open up the mendacious nature of this undercurrent.

My argument here is that the apparent unity of the caste under the right-wing is fictitious. Its existence in the discourse stems from not only our ignorance about how caste functions but also is carefully constructed to leverage certain nodal points of power for maximum use.

One can see why defining caste only in its traditional sense has led to the explosion of use of caste in our politics. Caste in our traditional discourse is understood in connection to ‘birth’ along with the axis of purity-impurity and sacred-profane.

I don’t wish to delineate these different strands of caste from one another, I wish to point towards another axis in this, which is that of traditional-modern. Usually when we bring caste system in our political discourse, the underlying assumption is that caste is a remainder of the traditional past that reason, rationality haven’t been able to conquer yet, this usually leaves out the reproduction of caste that is working through rationality itself. Our search for effects of caste system that blatantly stand against the modern rational mind is a way to block the everyday functioning of the caste that is embedded in modern rationality itself.

Our immediate but legitimate protests of grooms of lower castes not being allowed on the horse is also presupposed by the assumption that to find the effects of caste system one has to travel that much distance from where we live.

The unity of castes today is predicated upon this lens that first reduces caste to a remainder of the distant past, and then tries to ask where it is. It is in such a scheme that everyone of us with little privilege can believe that effects of caste exist but exist at a certain distance from us.

Breaking Away from Caste Oppression?

Rationality’s claim of a break from caste system stems from its ability to give us all the freedom to choose our ways of life, importantly choose our profession. It is this promises that-‘we can be anything we want to be’, that keeps the caste system at a distance. But this promise isn’t a replacement of caste but instead a covering under which new and old systems of caste have to find their existence. Numerous sociological works have shown this, without elaborating this in its detail, I will instead merely point out our discourse on merit. Why is it that we are quick to point out caste in some distant village but find it so difficult to convince an urban educated professional that merit replicates the effects of caste?

I am not saying that we should do away with merit or any of that radical stuff, but merely pointing out the obvious, which is that merit in many ways finds itself hands in glove with the caste system. The promise that ‘anyone can do anything’ is delicately balanced by a certain rationalization of work, whose job was to create alternate criteria to birth to enter into professions.

It is no surprise that these alternate entry points instead of replacing the criteria of birth have instead found its coexistence with effects of birth. This balancing act is done through the ball bearing of merit. Merit which should have been made up of practices that nurtures human creativity in our society has instead become a fulcrum through all these difference forces of exclusion find their rationality. The demand for reservation in private sector also can be understood through the above-mentioned facts. Its effects on our education system should be clear to anyone who is looking for them. The division of schooling into private, public, government aided etc. do not only reflect the class divide but in this way are also rooted into caste.

The traditional roots of caste and the modern democratic state even though belonged to different regimes of power but had long developed mechanisms of their coexistence. Caste no longer just needed the discourse of tradition to work its ways, it had long grown its roots in the discourse of enlightenment such as liberalism, secularism and so on. One can see these points of contacts in our debates on reservation; the strongest of these attacks never come from within the traditional discourse of caste system but from two strands that are ideals of the modern world.

One being merit as discussed before and the other being that caste itself shouldn’t be a category at all and instead should be replaced by economic parameters for reservation. Both these arguments not only miss the point of reservation as an act of social justice that requires the matrix of caste to be implemented but also show how misunderstood are effects of caste in this modern matrix. Reservation isn’t in itself just an equalising force but instead recognition of grave injustices that exist in our society and are reproduced by the very systems that aims to eradicate it.

You take away the category of caste from it and what would remain would just be doles, which without this force of social justice would just whither away. This does not mean that there cannot be arguments against reservation or we as a society don’t need that discourse also but shaping that discourse in this way symbolises the systemic nature of caste in which we all are implicated. For example, legitimate discourse against reservation can come from the communities to whom reservation is given as a right, like it did in the past with woman’s movements, but the space for that dialogue has not only shrunk, but has been made completely absent. The space for counter-narratives on reservation in these communities that was still present twenty years back has completely vanished today.

The Consolidated Presence of Caste in Indian Politics

The consolidation of caste that is happening under the right-wing today should be understood in this context. The end of Mandal-mandir politics, as it is sometimes called, where what Mandal commission divided, religious polarisation sought to unite, isn’t an end to role of caste in politics but is instead and end of old ways of understanding caste in its simplistic reality that emerged post implementation of Mandal report. The leaders that emerged through this politics, Mulayam Singh Yadav, Mayawati, Lalu Prasad Yadav etc. have mostly been side-lined in this election. But this has not happened because we have been able to imagine a world where we as a nation can rise above caste dynamics, but instead this has happened under the conditions that has completely strangled our imagination of anything new being possible. The coalitions thus formed are drenched in their transactional nature where at least for the time being our politics has abandoned hope of any new world and accepted the current systemic nature of caste. Coalition between Nitish Kumar’s JDU and BJP and even Akhilesh and Mayawati exactly emerged from this hopelessness. Thus, what we should expect now is not politics where caste calculations would considerably decrease or society where caste effects would be significantly diminished, on the contrary one can expect a rise of discourse that would again in one form or another seek to legitimise existing caste hierarchies again. The shape these hierarchies would take in urban and rural politics might be different but new unities and new overall strategies to intensify existing power relations between these different realities can be expected.