At a time when ‘Hindu icons’ are appropriated by the proponents of militant nationalism, it is not easy to invoke Swami Vivekananda. Furthermore, as the secular intelligentsia fails to engage with the realm of the spiritual, nothing seems to exist beyond the binaries of ‘right’ and ‘left’, ‘valorization’ and ‘condemnation’. However, the new generation growing up in these turbulent and confusing times ought to know that Swami Vivekananda—the action-oriented/university educated disciple of a remarkably simple and spiritually ecstatic Ramakrishna—was endowed with multiple possibilities. While in the age of colonial invasion he gave a distinctive identity to the resurgent nation with its ‘religious essence’ (not the aggression of fundamentalism, but the liberating soul as a guide line for managing the affairs of the world)’, he was also a saint with a hammer trying to transform Hinduism into an action plan for the upliftment of the subaltern. Even though he sought to create a ‘man making religion’ with ‘muscles of iron, nerves of steel and gigantic will’, like his master he was also a child of the feminine energy with a realization of the futility of male ego.

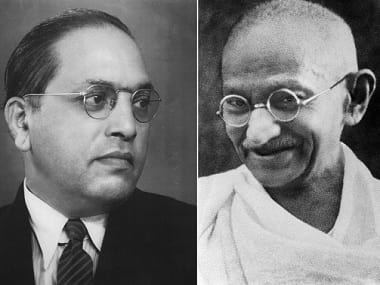

We know how the Marxists demystify the ‘opium’ called religion, and how, for the likes of Phule and Ambedkar, Hinduism with its caste-ridden hierarchical structure was seen to be a hindrance to the project of social emancipation. No wonder, these days in the radical/secular intellectual circuit we see a taboo on anything associated with Hinduism. Paradoxically, this taboo encourages militant Hindu nationalists to monopolize the entire discourse on Hinduism and its spiritual traditions. This must change; and liberal radicals including the Ambedkarites and Marxists must understand that a nuanced/creative/critical engagement with a monk like Swami Vivekananda is likely to generate new possibilities.

The intellectual hegemony( or a blend of Christianity and European sciences) that ‘benevolent’ colonial masters imposed on us seemed to have inspired a ‘renaissance man’ like Raja Rammohun Roy to fight idolatry and other obnoxious practices of Hinduism, and establish a highly sublime and intellectualized Brahmo Samaj causing a separation of the ‘intellectual’ from the ‘popular’. However, the arrival of Ramakrishna with his rural simplicity, spiritual ecstasy and catholicity was a turning point. With his folk wisdom and Vedantic metaphors, he could critique the new materialism that colonialism brought with it. As Vivekananda – a ‘university educated skeptic’— came closer to Ramakrishna, he came out of the temptation to fall into the trap of Brahmo elites, and became a ‘Hindu’ saint—but with a difference. In fact, the famous speech that the charismatic monk from the land of ‘oriental despotism’ delivered in the Chicago religious congress –a speech that reminded the world of the depths of the Upanishads— gave a new dynamism to the meaning of being a Hindu.

With his missionary zeal and celebration of ‘Practical Vedanta’, he spoke of the need to come out of the solitude of ‘forests, caves and mountains’, and enter into the actual realm of everyday action. True, Vedanta or the Upanishadic philosophy speaks of the all-pervading Brahma—the flow of eternal energy that passes through our finite/embodied existence; and the awakening of this energy enables us to conquer all sorts of fear and limitations of finitude. Practical Vedanta, for Vivekananda, is the ability to work with this boundless energy and excel as ‘cobblers, fishermen, traders and scholars’, and devote the fruits of our actions to the larger cause. Furthermore, his karmayoga—an innovative concretization of the Bhagavad Gita— further added to his immense popularity amongst the youth and even the revolutionaries of that era. Possibly, his religious practice was a living critique of the Eurocentric notion of ‘other worldly’ Hinduism.

Broadly speaking, in post-Vivekananda era the practice of Hinduism took three important turns. Sri Aurobindo left the realm of active politics, took a complete spiritual turn, and with meditative solitude contemplated on the dynamics of human evolution through ‘ascent and integration’ of the physical, vital, mental and psychic stages of one’s being. Then, through his ‘experiments with truth’ Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi made the active realm of politics as his field of sadhana, and aroused the imagination of a spiritually enriched composite culture filled with the non-violent spirit of perpetual cross-religious conversations. But then, Hinduism also took a militant turn which celebrated the principle of hyper masculine nationalism based on the centrality of ‘Hindu identity’. In fact, with Savarkar and Golwalkar Hinduism as a majoritarian doctrine became a weapon for unifying the ‘Hindu race’ by minimizing the influence of ‘alien intruders’. No wonder, violence was its natural sub-text.

As history poses a challenge before us in this hour of darkness, we need to engage with Vivekananda’s ‘Practical Vedanta’ and Gandhi’s dialogic Hinduism, enrich secularism as symmetrical pluralism through the ecstasy of spiritual oneness, and fight Hindutva or for that matter, any other fundamentalist force in the domain of politics and culture.

Prof. Avijit Pathak teaches at the Centre for the Study of Social Systems, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.