HEALTH

The establishment of community clinics that cater to the needs of the marginalized making healthcare accessible to a greater section of the masses is a key to universal health in India. Governments at central and state levels must emphasize the development and empowerment of such clinics to ensure public health and wellbeing.

Zeba Siddiqui is a Delhi based researcher interested in the field of public health.

The theme of the 2018 World Health Day, celebrated on April 7th, was ‘Universal Health Coverage: everyone, everywhere’. Universal Health Coverage (UHC), symbolizes the provision of essential health care services to citizens of a country. While it certainly does not imply treating everyone for everything, it does include financial protection as one of its primary goals. A catapult was witnessed recently when in the budget 2018-19, the government announced Ayushman Bharat Program, lauded as a precursor to India’s UHC.

The scheme garnered much attention for being the world’s largest governmentfunded healthcare program. It focusses on two broad verticals namely:

(1) Establishment of health and wellness centers for comprehensive health needs of people and (2) National Health Protection Scheme to provide a medical coverage of Rs.5 lakh per family.

The huge size of our population makes it necessary as well as challenging to percolate basic health services till the last mile. In this regard, Delhi’s ‘Mohalla Clinics’ demonstrate how community clinics can be a key linkage in the public health delivery system in India. ‘Mohalla Clinic’ is the flagship program of the Delhi government which began in 2015, and focused to establish at least a clinic in every slum locality. These clinics cater to the fundamental health needs and offer basic health service packages.

These facilities are run from porta cabins as well as rented premises and offer over 200 diagnostic tests and over a 100 essential medicines free of cost. Some of these facilities also make use of Android based tablets called ‘Swasthya Slate’ which can undertake a number diagnostic tests. The devices are also used by frontline health workers for antenatal care home visits. It is commendable how technology has been welded here, for these devices also help to maintain a health data collection. An aggregated data at the state level can help to identify health challenges specific to each region.

It is learnt from an official Delhi government notification that by July 2016 , nearly 8 lac people had sought health services from these clinics, while each clinic saw around 70-100 patients on each working day. Not too long ago when there was an outburst of Dengue and Chikungunya cases in the capital and the health facilities encountered a barrage of patients, the ‘Mohalla Clinics’ offered a much needed respite with their diagnostic test facilities.

The Lancet journal notes that these Mohalla Clinics ‚are successfully serving populations otherwise deprived of health services‛. Despite their promising results only 10% of the targeted clinics could be opened by the close of 2016. The delay in the same could be attributed to several reasons including paucity of land, insufficient quality checks, and absence of mid-course improvements amongst other things. Not with standing the lacunae, it can however be stressed that this is a model that holds immense potential for replication. While the government seeks to establish health and wellness centers as part of the aforementioned Ayushman Bharat Program, community clinics can offer a robust network of primary level facilities.

These centers can help offset the quantum of patients who approach secondary and tertiary level care even for their basic health needs. Oftentimes people who can afford, opt for private clinics as opposed to government run dispensaries , due to lack of confidence in the quality of the latter. A consistent and successful operation of the ‘Mohalla Clinics’ can reverse this trend and motivate the private clinic goers to avail government run facilities. Health is a state subject and a sustained engagement at the community level within each state can help build a wide network of health centers across the country and help pursue cooperative federalism in health sector. The Ayushman Bharat Program aspires to set up 1.5 lac wellness centers by 2022 and government can save its resources by leveraging from the already running ‘Mohalla Clinics’. Since community participation is one of the ten guiding principles of formulation of UHC in India, there are clear intersections between ‘Mohalla Clinics’ and a universal health care scheme.

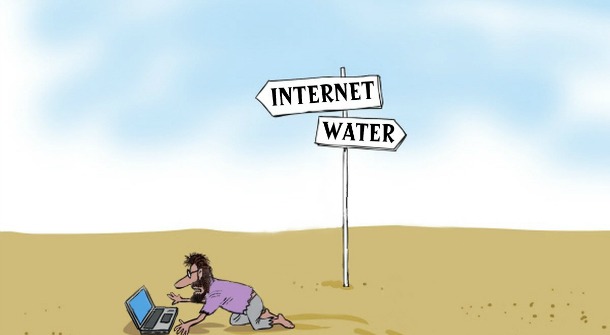

The chasm between the rich and poor have consistently been wide and enabling a universal model of healthcare at the rudimentary level can help plug these disparities. As 2019 general elections are approaching fast, it is important that our demands take a paradigm shift. This can be done for instance by bringing health to political discourse and making sure that the election manifestos go beyond the promises of electricity, water and roads.

***