A.S. Neil was a Scottish writer and educationist who created the Sumerhill School in England in 1921 and it continues to be a model for progressive and democratic schooling even now. The school was based on the idea that learning communities must be inclusive spaces where children do not fear adults, do not do things compulsively or feel regimented by routine. The Sumerhill is a space where free spirited education is practiced and the child is at the heart of his own educational process. Here is an engaging excerpt from A.S. Neil’s book ‘Sumerhill’ that explains his philosophy behind this iconic school.

This is a story of a modern school–Summerhill. Summerhill was founded in the year 1921. The school is situated within the village of Leiston, in Suffolk, England, and is about one hundred miles from London. Just a word about Summerhill pupils. Some children come to Summerhill at the age of five years, and others as late as fifteen. The children generally remain at the school until they are sixteen years old. We generally have about twenty-five boys and twenty girls.The children are divided into three age groups: The youngest range from five to seven, the intermediates from eight to ten, and the oldest from eleven to fifteen. Generally we have a fairly large sprinkling of children from foreign countries. At the present time (1960) we have five Scandinavians, one Hollander, one German and one American.

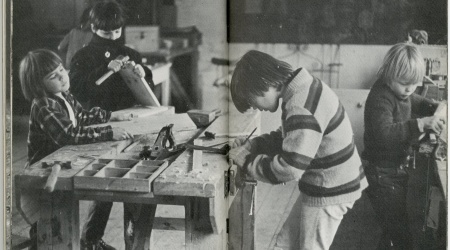

The children are housed by age groups with a housemother for each group. The intermediates sleep in a stone building, the seniors sleep in huts. Only one or two older pupils have rooms for themselves. The boys live two or three or four to a room, and so do the girls. The pupils do not have to stand room inspection and no one picks up after them. They are left free. No one tells them what to wear: they put on any kind of costume they want at any time. Newspapers call it a Go-as-you-please School and imply that it is a gathering of wild primitives who know no law and have no manners. It seems necessary, therefore, for me to write the story of Summerhill as honestly as I can. That I write with a bias is natural; yet I shall try to show the demerits of Summerhill as well as its merits. Its merits will be the merits of healthy, free children whose lives are unspoiled by fear and hate. Obviously, a school that makes active children sit at desks studying mostly useless subjects is a bad school. It is a good school only for those who believe in such a school, for those uncreative citizens who want docile, uncreative children who will fit into a civilization whose standard of success is money. Summerhill began as an experimental school. It is no longer such; it is now a demonstration school; for it demonstrates that freedom works.

When my first wife and I began the school, we had one main idea: to make the school fit the child–instead of making the child fit the school.

I had taught in ordinary schools for many years. I knew the other way well. I knew it was all-wrong. It was wrong because it was based on an adult conception of what a child should be and of how a child should learn. The other way dated from the days when psychology was still an unknown science.

Well, we set out to make a school in which we should allow children freedom to be themselves. In order to do this, we had to renounce all discipline, all direction, all suggestion, all moral training, and all religious instruction. We have been called brave, but it did not require courage. All it required was what we had–a complete belief in the child as a good, not an evil, being. For almost forty years, this belief in the goodness of the child has never wavered; it rather has become a final faith.

My view is that a child is innately wise and realistic. If left to himself without adult suggestion of any kind, he will develop as far as he is capable of developing. Logically, Summerhill is a place in which people who have the innate ability and wish to be scholars will be scholars; while those who are only fit to sweep the streets will sweep the streets. But we have not produced a street cleaner so far. Nor do I write this snobbishly, for I would rather see a school produce a happy street cleaner than a neurotic scholar. What is Summerhill like? Well, for one thing, lessons are optional. Children can go to them or stay away from them–for years if they want to. There is a timetable-but only for the teachers. The children have classes usually according to their age, but sometimes according to their interests. We have no new methods of teaching, because we do not consider that teaching in itself matters very much. Whether a school has or has not a special method for teaching long division is of no significance, for long division is of no importance except to those who want to learn it. And the child who wants to learn long division will learn it no matter how it is taught.

Children who come to Summerhill as kindergartens attend lessons from the beginning of their stay; but pupils from other schools vow that they will never attend any beastly lessons again at any time. They play and cycle and get in people’s way, but they fight shy of lessons. This sometimes goes on for months. The recovery time is proportionate to the hatred their last school gave them. Our record case was a girl from a convent. She loafed for three years. The average period of recovery from lesson aversion is three months. Strangers to this idea of freedom will be wondering what sort of madhouse it is where children play all day if they want to. Many an adult says, “If I had been sent to a school like that, I’d never have done a thing.” Others say,” Such children will feel themselves heavily handicapped when they have to compete against children who have been made to learn.” I think of Jack who left us at the age of seventeen to go into an engineering factory. One day, the managing director sent for him. “You are the lad from Summerhill,” he said. “I’m curious to know how such an education appears to you now that you are mixing with lads from the old schools. Suppose you had to choose again, would you go to Eton or Summerhill?”

“Oh, Summerhill of course” replied Jack.

“But what does it offer that the other schools don’t offer?”

Jack scratched his head. “I dunno,” he said slowly; “I think it gives you a feeling of complete self-confidence.” “Yes,” said the manager dryly, I noticed it when you came into the room.”

“Lord,” laughed Jack, “I’m sorry if I gave you that impression”

“I liked it,” said the director. “Most men when I call them into the office fidget about and look uncomfortable. You came in as my equal. By the way, what department did you say you would like to transfer to?”

This story shows that learning in itself is not as important as personality and character. Jack failed in his university exams because he hated book learning. But his lack of knowledge about Lamb’s Essays or the French language did not handicap him in life. He is now a successful engineer.

All the same there is a lot of learning in Summerhill. Perhaps a group of our twelve year-olds could not compete-with a class of equal age in handwriting or spelling or fractions. But in an examination requiring originality, our lot would beat the others hollow.

We have no class examinations in the school, but sometimes I set an exam for fun. The following questions appeared in one such paper: Where are the following:- Madrid, Thursday Island, yesterday, love, democracy, hate, my pocket-screw driver (alas, there was no helpful answer to that one). Give meanings for the following:- 9 the number shows how many are expected of each)- Hand (3)…. Only two, got the third right – the standard of measure for a horse. Brass (4)…. Metal, cheek, top army officers, department of an orchestra. Translate Hamlets, To-be-or-not-to-be speech into Summerhillese. These questions are obviously not intended to be serious, and the children enjoy them thoroughly. Newcomers, on the whole, do not rise to the answering standard of pupils who have become accustomed to the school. Not that they have less brainpower, but rather because they have become so accustomed to work in a serious groove that any light touch puzzles them.

This is the play side of our teaching. In all classes much work is done. If, for some reason a teacher cannot take his class on the appointed day, there is usually much disappointment for the pupils.

David, aged nine, had to be isolated for whooping cough. He cried bitterly. “I’ll miss Roger’s lesson in geography,” he protested. David had been in the school practically from birth, and he had definite and final ideas about the necessity of having his lessons given to him. David is now a lecturer in mathematics at London University. A few years ago someone at a General School Meeting (at which all school rules are voted by the entire school, each pupil and each staff member having one vote) proposed that a certain culprit should be punished by being banished from lessons for a week. The other children protested on the ground that the punishment was too severe.

My staff and I have a hearty hatred of all examinations. To us the university exams are anathema. But we cannot refuse to teach children the required subjects. Obviously, as long as the exams are in existence, they are our masters. Hence, the Summerhill staff is always qualified to teach to the set standard. Not that many children want to take these exams; only those going to the university do so. And such children do not seem to find it especially hard to tackle these exams. They generally begin to work for them seriously at the age of fourteen, and they do the work in about three years. Of course they don’t always pass at the first try. The more important fact is that they try again.

Summerhill is possibly the happiest school in the world. We have no truants and seldom a case of homesickness. We very rarely have fights – quarrels of course, but seldom have I seen a stand-up fight like the ones we used to have as boys. I seldom hear a child cry; because children when free have much less hate to express than children who are downtrodden. Hate breeds hate, and love breeds love. Love means approving of children, and that is essential in any school. You can’t be on the side of children if you punish them and storm at them. Summerhill is a school in which the child knows that he is approved of.