What do coal, viruses and DNA have in common? The structures of each – the predominant power source of the early 20th century, one of the most remarkable forms of life on Earth and the master molecule of heredity – were all elucidated by one person. Her name was Rosalind Franklin, and the story of her triumph over sexism and rise to scientific greatness is made even more remarkable by the fact that she lived only 37 years.

In Franklin’s day, sexism ran rampant in science. Her own father, judging science no career for a woman, actively discouraged her aspirations. Her doctoral supervisor at Cambridge, eventual Nobel Laureate Ronald G.W. Norrish, called her “stubborn and difficult to supervise” and offered little support. James Watson, whose Nobel Prize hinged in large part on her work, referred to her in his memoir as “Rosy” (against her preference), and stated that, because of her “belligerent moods,” colleagues knew she “either had to go or be put in her place.”

Despite the attitudes of those around her, Franklin maintained her scientific acumen and thirst for knowledge, crucially contributing to one of the greatest discoveries of the 20th century.

Becoming a chemist

Franklin was born in London on July 25, 1920 to a prominent family. Her great uncle served in the British Cabinet, and her father was a banker and science educator.

Franklin was an outstanding student. She received a scholarship to Cambridge, where she earned honors on her examinations and won a research fellowship. A lack of rapport with her supervisor, Norrish, drove her from his lab, and she ended up conducting groundbreaking research for her Ph.D. thesis on the molecular structure of coal.

Franklin then moved to Paris, where she studied X-ray crystallography, a powerful means of inferring the structure of molecules from how they bend beams of X-rays. She produced a number of important articles before returning to the U.K.

Assigned to work on the structure of DNA in her new position at King’s College London, she applied her knowledge of X-ray diffraction and created crucial images of its molecular structure. At the time, determining DNA’s structure was one of science’s holy grails.

Structure of life’s molecule

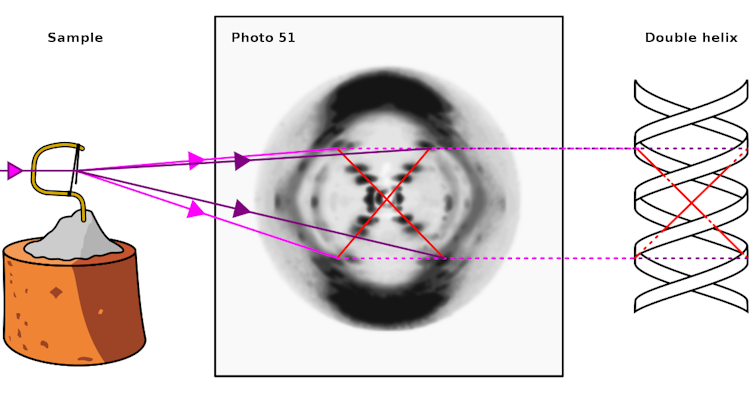

Recalling a moment in 1953, Watson described first seeing one of Franklin’s images of the DNA molecule, known as “Photograph 51”:

The instant I saw the picture my mouth fell open and my pulse began to race. The pattern was unbelievably simpler from those obtained previously. Moreover, the black cross of reflections which dominated the picture could only arise from a helical structure.

Watson and his Cambridge collaborator and eventual fellow Nobel Laureate Francis Crick were not doing laboratory research on the structure of DNA, but they were actively attempting to build a model of it. Franklin’s image provided them with a breakthrough. Franklin was a cautious scientist, believing that modeling should await airtight scientific evidence. But Watson and Crick were less hesitant and became convinced that their double helix model must be correct.

In 1953, when Watson and Crick announced their now famous double helix model for DNA, tensions at King’s College were driving Franklin to Birkbeck College. She joined John Bernal, an X-ray crystallographer known for promoting the careers of women.

There Franklin worked on characterizing the structure of RNA, another key information-bearing molecule in living organisms. She also studied the tobacco mosaic virus, the first virus shown to be harmful to a living organism, the tobacco plant.

During a trip to the U.S. in 1956, Franklin first noticed that she was having difficulty fitting into her clothes. Upon her return to London, she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, the result of mutations in the DNA of her own cells. Yet she did not let her illness interfere with her work and published a half dozen or more scientific papers in both 1956 and 1957. She died in April of 1958.

Franklin faced sexism for much of her professional life in science. Watson repeatedly described her in sexist terms in “The Double Helix,” criticizing her “choice” not to “emphasize her feminine qualities” and her lack of “even a mild interest in clothes.” Moreover, he and Crick chose not to reveal the extent to which their model depended on her DNA photograph.

Even in this atmosphere, Franklin was a great scientist, as captured in this passage from her obituary, composed by her mentor, Bernal:

She was distinguished by extreme clarity and perfection in everything she undertook. Her photographs are among the most beautiful X-ray photographs of any substance ever taken…. Her early death is a great loss to science.

Franklin’s reputation grew after death

Franklin certainly did not sink into obscurity.

One of her students, eventual Nobelist Aaron Klug, continued her work, helping to develop a new form of crystallography that relies on electrons instead of X-rays and advancing the understanding of the structure of viruses.

And of course initial skepticism about a double helix structure for DNA waned. Watson, Crick and another X-ray crystallography researcher at King’s College, Maurice Wilkins, received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962 for its identification.

Many have wondered why Franklin did not receive the Nobel Prize. First, she was never nominated, perhaps in part because of her gender. Another problem was the fact that the prize cannot be divided among more than three people, though some historians have argued that she deserved it more than Wilkins. Perhaps the most decisive reason is that Nobel Prizes are not awarded posthumously.

Franklin has been memorialized in many ways. King’s College and Cambridge University both created residence halls in her name, and Birkbeck established the Rosalind Franklin Laboratory. Her portrait now hangs next to those of Watson, Crick and Wilkins in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

And outside of Chicago is the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, which uses photograph 51 as its logo.

Franklin saw herself less as a female scientific pioneer than as a researcher whose work should be assessed purely in the light of her scientific contributions. Although she was not focused on gender, perhaps her greatest and most enduring legacy is the many women who have been inspired by her example to pursue scientific careers.![]()

Richard Gunderman, Chancellor’s Professor of Medicine, Liberal Arts, and Philanthropy, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.