Remember when Australians paid in shillings and pence? New research suggests the words for these coins and other culturally important items and concepts are the result of close contact between the early Germanic people and the Carthaginian Empire more than 2,000 years ago.

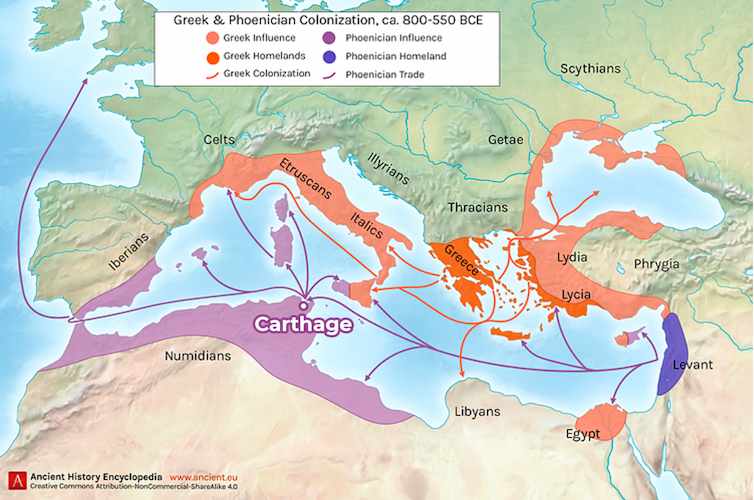

The city of Carthage, in modern-day Tunisia, was founded in the 9th century BCE by the Phoenicians. The Carthaginian Empire took over the Phoenician sphere of influence, with its own sphere of influence from the Mediterranean in the east to the Atlantic in the west and further into Africa in the south. The empire was destroyed in 146 BCE after an epic struggle against the Romans.

The presence of the Carthaginians on the Iberian Peninsula is well documented, and it is commonly assumed they had commercial relations with the British Isles. But it is not generally believed they had a permanent physical presence in northern Europe.

By studying the origin of key Germanic words and other parts of Germanic languages, Theo Vennemann and I have found traces of such a physical presence, giving us a completely new understanding of the influence of this Semitic superpower in northern Europe.

Linguistic history

Language can be a major source of historical knowledge. Words can tell stories about their speakers even if there is no material evidence from archeology or genetics. The many early Latin words in English, such as “street”, “wine” and “wall”, are evidence for the influence of Roman civilisation.

Punic was the language of the Carthaginians. It is a Semitic language and closely related to Hebrew. Unfortunately, there are few surviving texts in Punic and so we often have to use Biblical Hebrew as a proxy.

Proto-Germanic was spoken in what is now northern Germany and southern Scandinavia more than 2,000 years ago, and is the ancestor of contemporary Germanic languages such as English, German, Norwegian and Dutch.

Identifying traces of Punic in Proto-Germanic languages tell an interesting story.

Take the words “shilling” and “penny”: both words are found in Proto-Germanic. The early Germanic people did not have their own coins, but it is likely they knew coins if they had words for them.

In antiquity, coins were used in the Mediterranean. One major coin minted in Carthage was the shekel, the current name for currency of Israel. We think this is the historical origin of the word “shilling” because of the specific way the Carthaginians pronounced “shekel”, which is different from how it is pronounced in Hebrew.

The pronunciation of Punic can be reasonably inferred from Greek and Latin spellings, as the sounds of Greek and Latin letters are well known. Punic placed a strong emphasis on the second syllable of shekel and had a plain “s” at the beginning, instead of the “esh” sound in Hebrew.

But to speakers of Proto-Germanic – who normally put the emphasis on the first syllable of words – it would have sounded like “skel”. This is exactly how the crucial first part of the word “shilling” is constructed. The second part, “-(l)ing”, is undoubtedly Germanic. It was added to express an individuating meaning, as in Old German silbarling, literally “piece of silver”.

This combining of languages in one word shows early Germanic people must have been familiar with Punic.

Similarly, our word “penny” derives from the Punic word for “face”, panē. Punic coins were minted with the face of the goddess Tanit, so we believe panē would have been a likely name for a Carthaginian coin.

Sharing names for coins could indicate a trade relationship. Other words suggest the Carthaginians and early Germanic people had a much closer relationship.

By studying loan words between Punic and Proto-Germanic, we can infer the Carthaginians were culturally and socially dominant.

One area of Carthage leadership was agricultural technology. Our work traces the word “plough” back to a Punic verb root meaning “divide”. Importantly, “plough” was used by Proto-Germanic speakers to refer to a more advanced type of plough than the old scratch plough, or ard.

Close contact with the Carthaginians can explain why speakers of Proto-Germanic knew this innovative tool.

The Old Germanic and Old English words for the nobility, for example æþele, are also most likely Punic loanwords. If a word referring to the ruling class of people comes from another language, this is a good indication the people speaking this language were socially dominant.

Intersections of language and culture

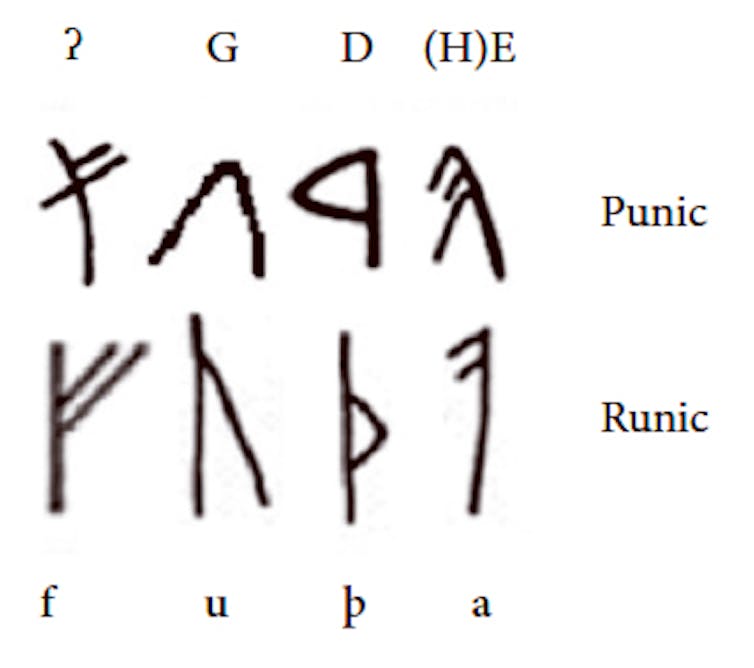

We found Punic also strongly influenced the grammar of early Germanic, Germanic mythology and the Runic alphabet used in inscriptions in Germanic languages, until the Middle Ages.

This new evidence suggests many early Germanic people learnt Punic and worked for the Carthaginians, married into their families, and had bilingual and bicultural children.

When Carthage was destroyed this connection was eventually lost. But the traces of this Semitic superpower remain in modern Germanic languages, their culture and their ancient letters.![]()

Robert Mailhammer, Associate Dean, Research, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.