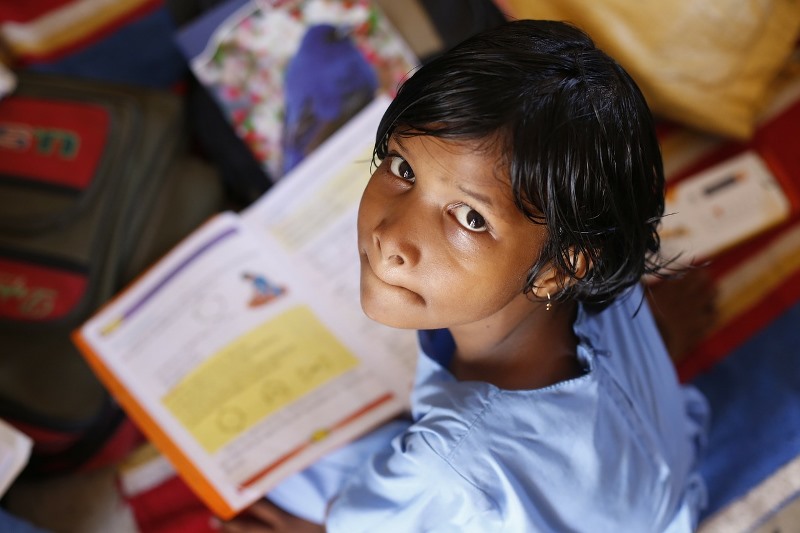

During the mid- 70’s I grew up in a para (a neighbourhood or locality having a strong sense of community solidarity) in North Bengal with my first 12 years surrounded by overtly friendly neighbours, uncles (kakus) and aunties (pishis), over a dozen friends (bondhu) with whom I would play in the evenings. Nandini di, was the eldest, then around 13 years of age and would in a way bully us to steal rice and sweets from our homes when we played doll-putuler biye (wedding of our dolls) it was called! Fights ensued, who would be in the bride’s side and who the groom’s! Hide and seek was our favourite and the entire para was our zone making it very difficult for the one who was the den! We were usually around 12 kids! Apart from hide and seek we played kit-kit. I do not know the English translation of it. Small squares were made and we used stones to jump and play on it. Siblings would end up in a brawl, teams (dall) would form that would end up fighting! There were also moments when we girls would in the early morning steal flowers for the morning pooja in our respective houses till we were chased by one granduncle (Dadu). I remembering panting and laughing with all my flowers strewn on the roadside. Like other friends, I too had a little basket. One fine day we spotted a mehendi tree in one of our distant neighbours’ courtyard, and decided that we would pluck as much leaves as possible and adore our hands with mehendi. We planned to steal in the afternoon while the family was resting. Entering through the gate to the courtyard was not difficult as those days locks or guards were never important. People could simply walk into each other’s houses. After stealing our bit, we climbed on another neighbour’s wall (pachil), perched ourselves, took a large stone and grinded the leaves to a paste and dabbed round blotches on our palms. Not all that happy about the design we agreed never to do it again! Uncles including my father would play badminton in the night in one of the empty plots of land. It was well organised as the land with cotton bushes and overgrowth got cleared and playing was almost an everyday event. We would also play there at times in the evenings. Smaller festivals such as Sankranti, Saraswati pooja, Dol (Holi) and Janmasthami were celebrated with such collective fervour and love now remain as beautiful childhood memories. Annual new year picnics were amazing. Almost all family members would join. Funds were collected, thakurs were arranged to cook food, all loaded in a truck with songs of the early 80’s playing loud and joyous. All that we as children did was enjoyed!

It was however not only in times of festivals or our play time that the extension of kindness, love and reciprocity was witnessed but also during times of ill health. I was once very unwell with a severe stomach ache. I was barely 8 years old. Baba was out of station for work and Ma was expecting. One evening it was unbearable and I had to be rushed to the doctor. One of Baba’s friends accompanied us to the doctor, someone took care of the house, someone later attended to my mother. It was all so sudden but help was immediate and without fail. Baba was informed that I had to undergo an immediate surgery for appendicitis. They got the best doctor in town, Dr. Chatterjee, a noted surgeon. Everything happened with all neighbours and friends around. My brother was born after few weeks at Dr. Mitra’s Nursing Home. I remember we had lot of visitors from my parents’ natal place – Darjeeling but inside our para and beyond we were never made to feel that we were not from the same linguistic community. Maybe it was our own socialisation, Ma was teacher then and Baba with a pharmaceutical company. His office guest house was not all that far. His colleagues and friends were also very kind and dear.

Many years have elapsed and now I have been living since the last two and half decades in Delhi and lately NOIDA. Over the years I have fought myself out amidst the cityscape’s demand of a desired status; marked by tangible assortations of wealth exemplified through owning a house, a car, fancy holidays and so on. I think I have now managed to convince my teenage son that such items of display are only momentary. Living in a rented apartment, an old smartphone, use of the metro until COVID took our travels away, availing of government LTC were obviously not conforming markers of a cosmopolitan status but to my son I say it’s alright. We must learn to live within our means and needs. I remember my father here who would tell us, “before you purchase, ask yourself do you really need it?”. Well, we live in a post-modern world now, and despite being hit by COVID we are unable to release the shackles of what connotes status, power. Simple gestures, friendliness and above all neighbourliness was always something that I yearned for. My moving to NOIDA from Delhi was both a personal as well as logistic requirement. It was not difficult to convince my house owner that we would be residing for the next six years until my son completes his high school. I took the liberty to facelift the house, have a separate entrance to the terrace after much objection from our neighbour. When we shifted I had politely introduced myself and my family members to my neighbour, only to their disgust. I did not augur this. Gradually I settled with life here in this apartment; a spacious one indeed with a terrace that allowed me to pursue my interest in gardening. Intermittent exchanges with my neighbours (women folk) from the terrace grew particularly during the period of the lockdown however measured or calculated it was perhaps. It took them few months or perhaps a year to accept a family like ours, who did not of course conform to the social milieu of North India until they saw us “celebrate” Deepawali.

COVID then caught all of us one day in the month of October 2020. It dragged my period of illness to almost 6 weeks. Diwali was the day after we tested negative. Not that we were on any account planning to “celebrate” but it was more to do with my emotional familial attachment towards it. My natal family was away then and with illness had made it all the more morose. It was beyond my imagination that we would be so scornfully detested by our immediate neighbour. I greeted and attempted to talk normally as one always does during the festival of Diwali only to be ignored. I was too tired to think that day. I just sat on the stairs and placed the diyas. Stigma was something that I had read in texts but experiencing something so explicit, it took some time to heal. It was almost as if the entrance to our flat was like a garbage dump. Domestic helps too were perhaps told to keep away. I cannot imagine the scorn that individuals and families must have faced during the onset of the pandemic when houses were ‘labelled’. My cook, when she resumed work in a light – hearted manner mentioned that her friends were asking, “was she not scared to work in our house”? My other help informed me that the neighbour’s maid has stopped talking with her and they would keep a distance from her if they happened to meet around the staircase. Such was the scorn! Not even the festival of colour helped me to heal the pain I felt during Diwali. Both these festivals have meaning for me at least within the idea of a neighbourhood. The previous year we had celebrated and there was exchange of ‘gifts’ between neighbours. Last year there was none. The response as we recuperated from COVID was more painful than the suffering itself. I wonder how things would have been had the pandemic struck in the mid 70’s. Would people in a para whole-heartedly extend support or would they be as callous as we experienced here and stigma been more acute? I wonder. COVID is increasing at an alarming rate in the society where we live, and my workplace; frightening our wits thinking about its tenacity and anxious as never before about the second dose of vaccination. Has hell broken lose?

Rinju Rasaily teaches Sociology at Ambedkar University, Delhi.