Sophie in the Company of Marx and Sartre: The Tale of a Fascinating Pedagogic Engagement

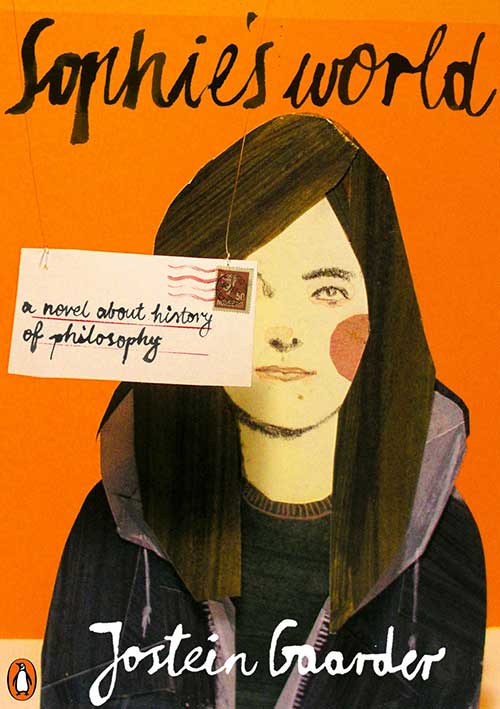

See how the back cover of this brilliant book (Sophie’s World) introduces the theme: “ Looking in her mailbox one day, a fourteen-year old Norwegian schoolgirl called Sophie Amundsen finds two surprising pieces of paper. On them are written the questions: ‘Who are you?’ and ‘Where does the world come from?’ The writer is an enigmatic philosopher called Alberto Knox, and his two teasing questions are the beginning of an extraordinary tour through the history of Western Philosophy from the pre-Socratics to Sartre. In a series of brilliantly entertaining letters, and then in person, Alberto Knox opens Sophie’s enquiring mind to the fundamental questions that philosophers have been asking since the dawn of civilization.”What fascinates us is the extraordinary pedagogic potential of the book—its conversations and dialogues. And it also demonstrates the great power of stories and narratives in the meaningful transaction of ideas. Philosophy is not something esoteric—a text filled with bad prose and difficult words; philosophy emanates from life—its wonder and curiosity. And a great teacher is gifted with the art of communication. Jostein Gaarder has charmed us, inspired us, and made us believe that life is philosophical and teaching is rhythmic communication. The New Leam believes that its alert readers should see themselves as Sophie, and realize what it means to be in the company of a great pedagogue. In this excerpt Marx and Sartre have become alive, and yes, philosophy has become enchanting once again.

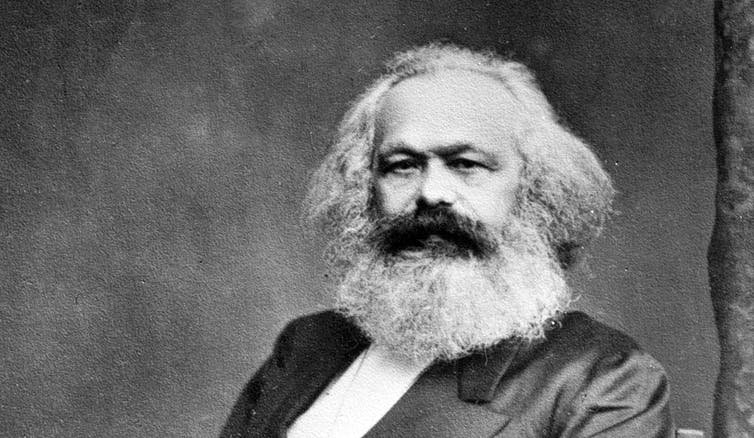

How we work affects our consciousness

‘Before he became a communist, the young Marx was preoccupied with what happens to man when he works. This was something Hegel had also analyzed. Hegel believed there was an interactive, or dialectic, relationship between man and nature. When man alters nature, he himself is altered. Or, to put it slightly differently, when man works, he interacts with nature and transforms it. But in the process nature also interacts with man and transforms his consciousness.’ ‘Tell me what you do and I’ll tell you who you are. ‘That, briefly, was Marx’s point. How we work affects our consciousness, but our consciousness also affects the way we work. You could say it is an interactive relationship between hand and consciousness. Thus the way you think is closely connected to the job you do.’ ‘So it must be depressing to be unemployed.’ ‘Yes. A person who is unemployed is in a sense, empty. Hegel was aware of this early on. To both Hegel and Marx, work was a positive thing, and was closely connected with the essence of mankind.’ ‘So it must also be positive to a worker?’

‘Yes, originally. But this is precisely where Marx aimed his criticism of the capitalist method of production.’ ‘What was that?’ ‘Under the capitalist system, the worker labors for someone else. His labor is thus something external to him—or something that does not belong to him. The worker becomes alien to his work—but at the same time alien to himself. He loses touch with his own reality. Marx says, with a Hegelian expression, that the worker becomes alienated.’ “I have an aunt who has worked in a factory, packaging candy for over twenty years, so I can easily understand what you mean. She says she hates going to work, every single morning.’ ‘But if she hates her work, Sophie, she must hate herself, in a sense.’ ‘She hates candy, that’s for sure.’ ‘In a capitalist society, labor is organized in such a way that the worker in fact slaves for another social class. Thus the worker transfers his own labor—and with it, the whole od his life—to the bourgeoisie.’ ‘Is it really that bad?’ ‘We are talking about Marx, and we must therefore take our point of departure in the social conditions during the middle of the last century. So the answer must be a resounding yes. The worker could have a 12-hour working day in a freezing cold production hall. The poor was often so poor that children and expectant mothers also had to work. This led to unspeakable social conditions. In many places, part of the wages was paid out in the form of cheap liquor, and women were obliged to supplement their earnings by prostitution. Their customers were the respected citizenry of the town. In short, the precise situation that should have been the honorable hallmark of mankind, namely work, the worker was turned into a beast of burden.’ “That infuriates me!’ ‘It infuriated Marx too. And while it was happening, the children of the bourgeoisie played the violin in warm, spacious living rooms after a refreshing bath. Or they sat at the piano while waiting for their four-course dinner. The violin and the piano could have served just as well as a diversion after a long horseback ride.’ ‘Ugh! How unjust!’

Man is condemned to be free

‘The key word in Sartre’s philosophy is “existence”. But existence did not mean the same thing as being alive. Plants and animals are also alive, they exist, but they do not have to think about what it implies. Man is the only living creature that is conscious of its own existence. Sartre said that a material thing is simply “in itself”, but mankind is “for itself”. The being of man is therefore not the same as the being of things.’ ‘I can’t disagree with that.’ ‘Sartre said that man’s existence takes priority over whatever he might otherwise be. The fact that I exist takes priority over what I am. “Existence takes priority over essence.” ‘ ‘That was a very complicated statement.’ ‘By essence we mean that which something consists of—the nature, or being of something. But according to Sartre, man has no such innate “nature”. Man must therefore create himself. He must create his own nature or “essence”, because it is not fixed in advance.’ ‘I think I see what you mean.’ “Throughout the entire history of philosophy, philosophers have sought to discover what man is—or what human nature is. But Sartre believed that man has no such eternal “nature” to fall back on. It is therefore useless to search for the meaning of life in general. We are condemned to improvise. We are like actors dragged onto the stage without having learned our lines, with no script and no prompter to whisper stage directions to us. We must decide for ourselves how to live.’ ‘That’s true, actually. If one could just look in the Bible—or in a philosophy book—to find out how to live, it would be very practical.’ ‘You’ve got the point. When people realize they are alive and will one day die—and there is no meaning to cling to—they experience angst, said Sartre. You may recall that angst, a sense of dread, was also characteristic of Kirkegaard’s description of a person in an existential situation.’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Sartre says that man feels alien in a world without meaning. When he is describing man’s “alienation”, he is echoing the central ideas of Hegel and Marx. Man’s feeling of alienation in the world creates a sense of despair, boredom, nausea, and absurdity.’ ‘It is quite normal to feel depressed, or to feel that everything is just too boring.’ ‘Yes, indeed. Sartre was describing the twentieth-century city dweller. You remember that the Renaissance humanists had drawn attention, almost triumphantly, to man’s freedom and independence? Sartre experienced man’s freedom as a curse. “Man is condemned to be free,” he said. “ Condemned because he has not created himself—and is nevertheless free. Because

having once been hurled into the world, he is responsible for everything he does.” ‘ ‘But we haven’t asked to be created as free individuals.’ ‘That was precisely Sartre’s point. Nevertheless we are free individuals, and this freedom condemns us to make choices throughout our lives. There are no eternal values or norms we can adhere to, which makes our choices even more significant. Because we are totally responsible for everything we do. Sartre said that man must never disclaim the responsibility for his actions. Nor can we avoid the responsibility of making our choices on the grounds that we “must” go to work, or we “must” live up to certain middle-class expectations regarding how we should live. Those who thus slip into the anonymous masses will never be other than members of the impersonal flock, having fled themselves into self-deception. On the other hand our freedom obliges us to make something of ourselves, to live “authentically” or “truly”.’

Jostein Gaarder, Sophie’s World: A Novel about the History of Philosophy, Phoenix, London, 1995.

This article is published in The New Leam, MARCH 2017 Issue( Vol .3 No.22 – 23) and available in print version. To buy contact us or write at thenewleam@gmail.com

The New Leam has no external source of funding. For retaining its uniqueness, its high quality, its distinctive philosophy we wish to reduce the degree of dependence on corporate funding. We believe that if individuals like you come forward and SUPPORT THIS ENDEAVOR can make the magazine self-reliant in a very innovative way.