Striving for the Peaks of Beauty and Nobility

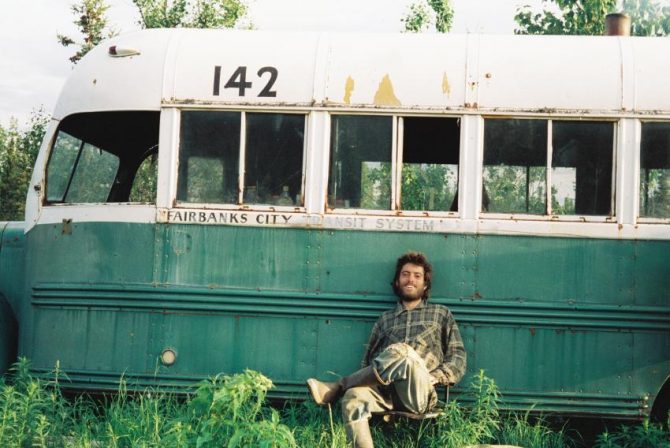

Learning is a continual journey—a process of exploration. As children climb the mountain to reach their school we feel the aesthetic play of nature,we converse with them, we learn and unlearn, and nature begins to heal and inspire

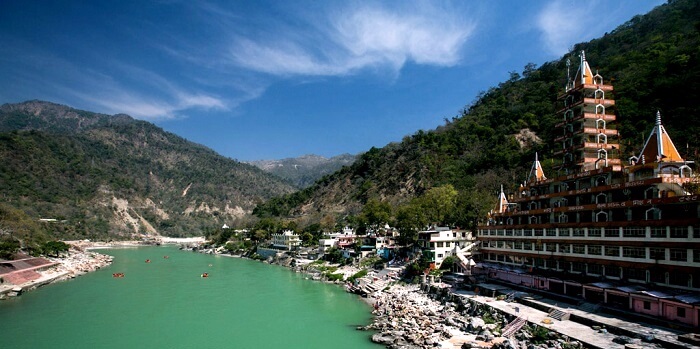

Nature is our finest tutor. As humble learners we feel like coming back to nature time and again. Its rhythm and wonder, its mystery and metaphysics teach us many lessons that no university can offer. Its abundance—the sky filled with planets and stars, snow clad mountains and tall trees—brings us closer to Tagore and Whitmam; the Upanishadic prayer begins to make sense; and God, we realize, is essentially the spirit of interconnectedness: a butterfly coming closer to tiny flowers, birds looking at the sunrays touching the grand Himalayan peaks, and we ordinary mortals are expressing our gratitude to the Divine because He has given us the eyes to see, the ears to receive the music of silence.

We are at Kausani—a Himalayan hamlet in Uttarakhand. As far as the rationale of tourism industry is concerned, Kausani is a ‘spot’, and hence it is about ‘having’: spend money, stay in hotels and resorts, order food and wine, grab the ‘sunrise’, capture it in your camera, and then move—move fast—towards another ‘spot’: another round of ‘having’. Yes, tourism as an industry destroys the art of seeing, destroys relatedness and contemplation; it promotes a culture in which nothing is more important than instant consumption. Possibly the task of liberating education is to rescue and cultivate the art of seeing.

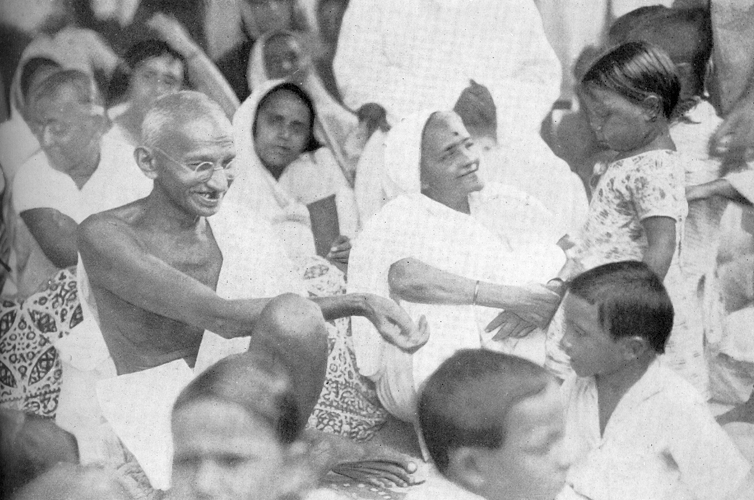

This light rescues us. Kausani, for us, is not a ‘spot’; it is beyond categories—even beyond Gandhi’s Kausani (Kausani inspired Gandhi to reflect on the Bhagavadgita and its principle of detached action). Its every moment is our moment of realization; its sunrise illumines our inner selves; its sunset generates the most profound music of melancholy; its devdar trees and birds and clouds talk to us; and an old man walking—and walking slowly and beautifully—through its rhythmic path is a living poem that defies urban restlessness and chaotic speed. Kausani enters us. We do not ‘grab’ Kausani; instead, it elevates us.

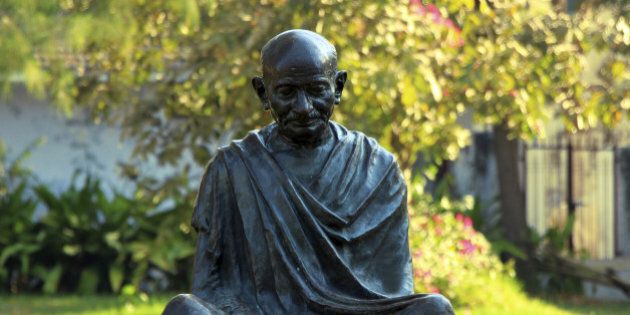

With elevated souls we begin to climb the mountains, enter the Kendriya Vidyalaya campus. Unlike what we see in schools in Delhi, there is no security guard, no interrogation, no suspicion. We come to the office, introduce ourselves, and express our willingness to meet the Principal. The office staff requests us to wait and sit in the Principal’s room. We see the pictures of Vivekanda, Gandhi and Premchand; we feel the ambience, its warmth. Meanwhile, Mr. Lalit Prasad Sah—the Principal of the school—arrives. His radiant smile welcomes us; we feel easy and comfortable. We share our ideas and experiences. And it becomes clear to us that we are talking to a teacher—an eager/enthusiastic teacher, not just an administrator.

No wonder, he makes it possible for us. A group of ten children (of standard IX-X), and a young mathematics teacher join us. We begin our conversation. To begin with, what strikes us is their simplicity and innocence. They are not like the children of the privileged classes we come across in a city lile Delhi: pampered and armoured with costly toys and gadgets and ‘smart’ talk, but devoid of the innocence of childhood. Is it beause of the grace of nature? Is it because of ther economy and everyday struggles? Or is it because of the fact that global capitalism has not yet made them ruthlessly ambitious?

They take some time to open up; their shyness is their beauty. Moreover, they are not particularly easy with English—the ‘cultural capital’ through which, to borrow Pierre Bourdieu’s reamarkably penetrating insights, schools reproduce social inequality. However, we are amidst nature; mountains, clouds and snow peaks speak a language that is universal; and hence a communion is established. Something happens. They surprise us. ‘I wish to be a dancer’, says a girl. ‘And I wish to be an athlete’, says yet another child. Seldom do you find such responses because we are living at a time when children are led to believe that not to try to be an engineer or a doctor or a civil servant is something pathological. No wonder, these two children inspire us to continue the conversation. ‘Do you think that your parents would agree woth your idea?’ we ask them. ‘No. They would say that it is risky, it is not a secure career’, they reply. Yes, they are aware of the fact that it is not easy to find one’s vocation, to pursue what one likes . Society means pressure; society means fulfilling others’ expectations; society means standardization—death of uniueness and creativity.

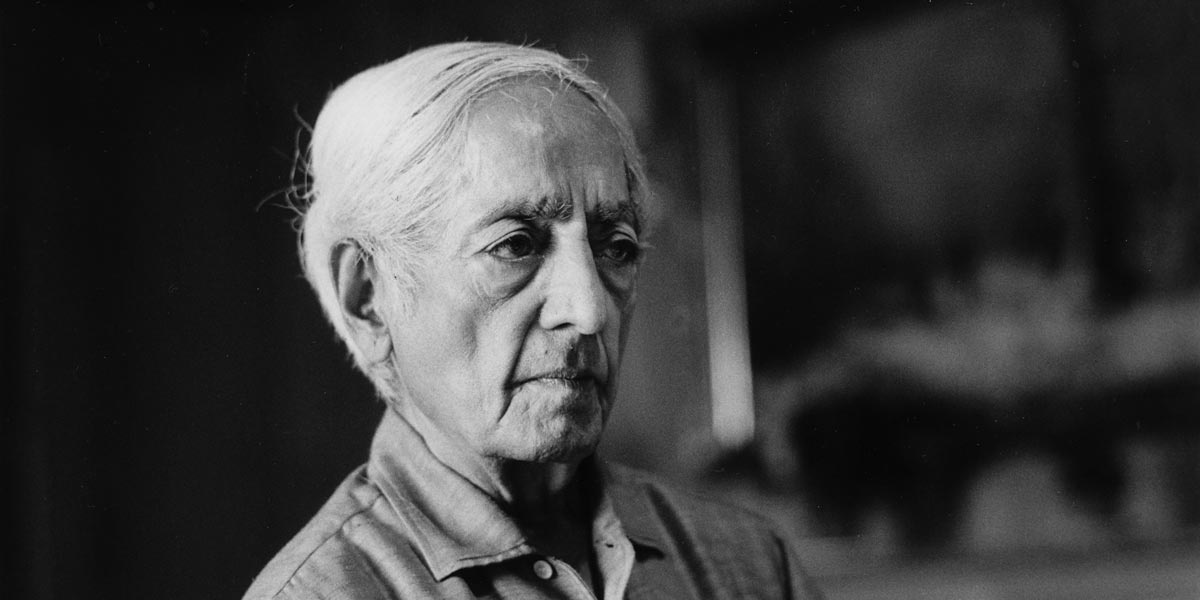

We look around. And suddenly a flash of truth illumines us. A mountain peak is a mountain peak; a bird is a bird; a butterfly is a butterfly; a devdar tree is a devdar tree; there is uniueness, yet there is relatedness. But then, why is it that we humans have deviated ourselves from this simple and profound truth? In our society someone who could have become a good dancer becomes an accounant in a real estate company; someone who could have become a good athlete becomes a clerk in a municipality office. It is about pain, alienation and loss of creativity. John Dewey was right in his obsevation: ‘Nothing is more tragic than failure to discover one’s true business in life, or to find that one has drifted or been forced by circumstances into an uncongenial calling.’ Is it the destiny of a modern form of education that privileges utility rather than creativity? Is it because the process of denaturalization is almost complete? Or is it the fate of a typical ‘Third World’ country like ours in which the scarcity of opportunities and associated desire for a ‘safe’ career paralyze all noble aspirations and dreams?We leave their school. We keep reflecting. Is it possible to create a pedagogic milieu in which children are encouraged to articulate their likes and dislikes, an environment that inspires them to know themselves, a group of teachers who can make them feel the wonder of what Robert Frost would have regarded as ‘the path less travelled’? Meanwhile time has passed. The moon has arrived; the mountains are becoming like sufi mystics; it is becoming difficult for us to separate these children from this extraordinary beauty of nature. We begin to pray for them. And this exploration makes us realize that it is this shared prayer that unites the teacher and the taught, and helps them to touch the peaks of beauty and nobility, and overcome the societal fear and pressure.