Taking Deleuze to Classrooms

A constant challenge before the creative pedagogue is to be able to enliven the classroom through the participation of the learners.

Saurabh Todariya is working with the government primary schools in Uttarakhand and is interested in developing the phenomenological approach towards education and learning.

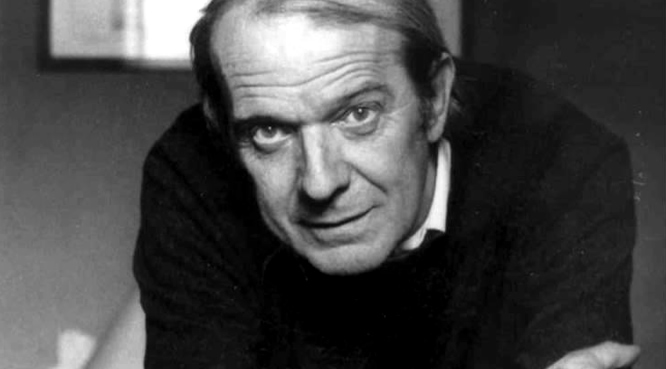

Here the author tries to take Gilles Deleuze’s ideas on ‘image of thought’ to the classrooms of Uttarakhand and discover the implications it may hold for the young learners. Gilles Deleuze (1925-95) is one of the most important thinkers of our age whose ideas have profoundly influenced the discourses in philosophy and social sciences. His ideas on difference, repetition, intensity, rhizome, schizophrenia have provided the various openings to look afresh the problems in philosophy and politics. In his entire academic life, Deleuze has created the various concepts and vocabularies to interpret the human life and experiences. In this article, we would explore Deleuze’s ideas on ‘image of thought’, which he develops in his book, ‘Difference and Repetition’ in relationship with the condition of government primary schools in Uttarakhand. The purpose of this interface is twofold: First, this would help us to appreciate the classroom conditions in Uttarakhand and see its implications for a child. Second, it would try to bring Deleuze from seminar rooms to the field, the gesture which I believe Deleuze would have appreciated.

In order to understand Deleuze’s idea of ‘the image of thought’ and its relevance to our study, we need to analyze Deleuze’s complex relationship with Kant. In fact, Deleuze’s work Difference and Repetition can be seen as a kind of encounter with Kant’s critical philosophy.

For Kant, the central problem in Critique of Pure Reason is how does the experience become possible? It is a fact that we experience the world in the ordered and meaningful way, but what are the structures which provide this order? Kant’s argument is that these structures are a priori. They are not derived from the senses; rather they provide order to the chaotic impressions from the senses. Kant calls this structure as ‘categories’. We have certain fundamental categories which order the sensations into a meaningful way. Thanks to the categories, the world does not become the chaos of sensations but appears as an ordered structure in which we orient ourselves. Kant argues that there must be a transcendental principle which would synthesize the various bits of sensations and convert into a kind of ‘my experience’. By transcendental Kant means not something other worldly or divine. It means the conditions or background which arranges and structures the experience in a priori manner. In the absence of such a synthetic principle, the various inputs of the sensations would be lost and we won’t be in the condition of recounting any experience. He calls this synthetic principle as ‘transcendental unity of apperception.’ The transcendental unity of apperception synthesizes, retains, reproduces the various bits of experiences and gives rise to the feeling of ‘self’. This transcendental unity of apperception therefore is the highest principle and acts as the logical necessity for any experience to take place.

Gilles Deleuze problematizes the notion of synthesis in Kant. Kant in the first Critique has produced a very intricate and subtle process of the synthesis in which he argues that until we are in the condition of re-cognizing the earlier cognition, the perception would not take place. Hence, the ‘synthesis of recognition’, holds key for the possibility of experience. Deleuze argues that the logic of recognition in Kant gives priority to identity over difference, which is in consonance with the tradition of philosophy in the West. Since the senses always produce the excess, so the thoughts try to control it through inventing the concept so that the excess of the experience can be controlled. Although Kant himself argues in Critique of Judgment that aesthetic experience cannot be treated like the everyday experience as in aesthetic judgment we reflect on the beauty of the object without putting it into any particular concept. The playfulness of the concepts produces the joy which distinguishes aesthetic experience from the other kinds of experience. Deleuze argues that even the everyday experience also holds the potential for the possibility of this playfulness; however, the logic of recognition produced through the biopolitical system tries to arrest the excess of the experience through inventing the category of identity.

Deleuze calls this tendency to generalize the differences as the ‘image of thought’. Thought already works under this image and tries to minimize and arrest the voluptuousness of the experience by subsuming the differentials into one category. Deleuze therefore gives more importance to experience than concepts. In Kant, the subject and object does not influence each other. Subject is merely a logical condition or principle which unites the various bits of the experience into a coherent whole. While doing so, it remains unchanged. Deleuze however argues that self also get affected by the experience and transforms itself vis a vis experience. Hence, in any new experience subject re-configure itself; that is why, for Deleuze subject is an assemblage of the various experience and nothing essential belongs to it. Bringing Deleuze’s ideas in the government primary schools in Uttarakhand highlights the fact that our educational system is promoting the ambience where children are laboring for the ‘dogmatic image of thought’, in the form of existing syllabus, teaching method and memorization of facts. As such, children are not being prepared for encountering something new in the experience. This results in hampering the creativity of mind which a child naturally possesses. Deleuze emphasizes on experience rather than concepts for thinking. It is the experience only which provides the impetus for thinking and in the process of thinking only, the various kinds of concepts could be generated. So if we extend Deleuze’s thoughts to our educational system, we can argue that any curriculum, teaching method, classroom space or mode of assessment should provide the opportunities to a child to experience something different so that she can develop the reflective capacities.

Unfortunately our current school system is fostering the pattern which is emphasizing more on the faculty of memory than thinking. This can be understood through analyzing the relationship between the teaching and assessment methods in our government schools. In government schools, the assessment is basically done through the examination methods. Through oral and written examinations, teachers assess the learning levels of a child. Since learning levels have been already defined and provided by the state government for every class so the child is assessed on the basis of these parameters by teachers. Given this situation, a school teacher finds memorization of facts as the only way to cope up with the system. That is why, teachers emphasize on the memorization of facts, emphasis on the text books and punishment in their classrooms. In a system where the level of learning is judged under a pressure situation of examination, there cannot be the time left for the creativity and reflection as it would not be taken into consideration in the final assessment. The everyday classroom condition in most of the government schools displays the consequence of such approach. The walls of the classrooms are generally empty and do not have something which can arouse the imagination of the child. Very few schools have the learning materials or pictures on display. The teaching method is text books based and emphasizes on the memory and reproduction of facts. In the mechanical system teachers do not see the point that they can also teach children by taking some local context and can generate interest in learning and writing as well. As we have seen in our interaction with children that whenever a child is asked to narrate her experience, she takes a lot of interest in writing as it becomes the mode of expressing her-self.

Such a classroom from Deleuze’s point of view is laboring for the ‘logic of recognition’ as it is not promoting the space where something different can emerge. Classroom should be the space where different kinds of experiences can be shared and nurtured in the presence of the teacher. On the contrary, all the particulars are subsumed under a general concept. However, when we create a free space for children to interact and share their experiences, a lot of interesting things come out which becomes a transformative experience for us. In a classroom when we asked the children about the sources of water, they re

sponded in the text-book fashion by naming a few sources of water like rain, rivers, ponds etc. However, when we asked them to tell us what could be the other sources of water they can think of other than the text books, they took a lot of interest in the activity and told us so many sources like handpump, tap, village pond etc. However, a girl gave a very touching answer when she said that ‘eye is also a source of water!‛. This filled us with wonder about the creativity of children. The encounter between Deleuze and government school’s classroom in the hilly state of Uttarakhand corroborates the widespread belief that government schools are not able to foster the creativity in children and there has been a public dismay regarding the performance and quality of these schools. This shows in the low enrollment in the government schools and the mushrooming of the private schools even in the region. However, there are some rays of hope as well. In Bageshwar, a government official promoted the concept of Deewar Patrika in all the schools. Teachers were asked to paste the drawing, stories and crafts by child in the school walls at one place. This has made the classrooms more alive, creative and colorful.

References

Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition. Trans. Paul Patton. NewYork: Columbia University Press, 1968.

Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Pure Reason. Trans.

Kemp Smith. NewYork: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. <<Critique of Judgment.

Trans.Werner Pluhar. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.1987. …. Prologemena to Any Future Metaphysics. Trans. Gary Hatfield Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

This article is published in The New Leam, MAY 2017 Issue( Vol .3 No.24 ) and available in print version. To buy contact us or write at thenewleam@gmail.com

The New Leam has no external source of funding. For retaining its uniqueness, its high quality, its distinctive philosophy we wish to reduce the degree of dependence on corporate funding. We believe that if individuals like you come forward and SUPPORT THIS ENDEAVOR can make the magazine self-reliant in a very innovative way.