Educating teachers about any knowledge and skill one wants to teach children seems to be the most straightforward job. First, go and educate teachers, and then expect them to pass it on to the students using different pedagogical methods convenient to them. With the same thought in mind, a colleague and I reached out to two government schools in the Poraiyahat block of Godda district in Jharkhand. Godda district falls under the Santhal Pargana division of Jharkhand and is among the top two in child marriage statistics in Jharkhand.

My colleague and I are currently working on exploring pedagogical ways of teaching children a few skills needed to engage in Dialogue; how to make conscious efforts in listening to others, the ways one can ask open-ended questions to know more about the issue, and the feelings of the other person, carefully stating one’s opinion, and engaging in a constructive way of exchanging perspectives, referred to by scholars as structured academic controversy.

So, we contacted the school masters, who welcomed us warmly and enquired a bit about our work. Both the headmasters had called a few teachers to come and talk to us so that everybody knew what was happening. This simple practice was worth appreciating, and we instantly felt that Power structures, at least in those two government schools, were not as concrete as we have observed in a private school in the same block. Moreover, the headteachers also take subject classes, which could be because the teachers are less in number; in this way, they also get to understand and empathize with the everyday struggles of teachers within the classroom. Therefore, all of them listened to us carefully and analyzed if our engagement would help them. They soon agreed and asked us to come a day after. These are cluster schools, meaning they work as resources/nodes for several other small schools. So, the number of teachers attending the workshop in each of these schools was about 18 to 20, and the number of male teachers was thrice the number of female teachers in both the schools. On the first day, they attended the workshop, laughed during the activities, and discussed the difference between destructive and constructive ways of dealing with a conflict. They appreciated the workshop and shared that such workshops on resolving conflicts hold a strong potential for a peaceful world.

Amidst all appreciation, a teacher raised an important concern about taking such workshops to their classrooms. The teacher said that such skills and work towards a better and peaceful world are essential, but one must rethink when trying to take it to the classroom. He shared that teachers are burdened with work; one has to finish the syllabus, take regular tests, evaluate those tests, go on to the next unit, and follow the same pattern. In addition, teachers are sent for evaluations in other schools, duties during elections, vaccinations, and any other task in which government needs human resources. Integrating such activities with lesson planning and practicing requires time, energy, space, and a burden-free environment. Moreover, constant pressure and scrutiny of the “orders from above” demand them to finish the syllabus on time, conduct tests, and bring the numbers.

This teacher’s concerns were rooted in his years of experience and were the voices of several other teachers from whom we expect to deliver any pieces of knowledge and skills shared with them instantly in the classroom. Similarly, in the other school, the head teacher asked us to wait for a week for the next session as the teachers were busy in evaluation; the following week, the teachers were engaged in writing reports because of some expected official visits for inspection. So only after a month or so could we do the second workshop. Our struggle with not getting dates for doing a workshop was a reflection of the challenges that teachers face while trying to teach new ideas in the classroom, experiment with pedagogical approaches, and integrate a valuable set of knowledge and skills into the lesson plan.

Such challenges raise a few questions concerning our work on Dialogue and Social Justice with teachers; How do teachers’ see their role in the transformation of education? How do they understand their worth in changing the discourse of Peace and Justice? It is often said that one necessary condition of Peace is that Justice precedes it, then how does one analyze peace in the lived reality of teachers? Where is the space for dialogue, teaching, and learning to dialogue? How does one practice and teach compassion in the everyday uptight environment of seeing oneself as only a labor force, without any space for making choices? These questions demand a look at the nature of current institutional structures that teachers a part of.

Institutional structures play a crucial role in deciding how employees function. Often, these structures are patriarchal, violent, operate without consent, and prefer orders over dialogue. As part of these institutional structures, teachers experience its patriarchal nature in their day-to-day activities. They, as powerless, accept the embedded-indirect-violence, and starts living, sometimes replicating the same, as “this is how the world works.” This percolation of hidden violence sums up the operation and the replication of the hierarchical and hegemonic structures within the current education system.

Envisioning the transformative values of Dialogue, Compassion, and Social Justice

So, What is the role of education for dialogue, compassion, and social justice in this continuous replication of violence? The position it takes is of envisioning a transformative educational structure with its roots firmly settled in the conceptual framework of love, care, freedom, empathy, and compassion. It envisions an education system embedded in social justice and democratic education and informs the possibilities of critical hope and dialogue leading towards a nicer world. This vision attempts to transform these replicating patriarchal-coercive structures by reviving the elements of empathy, compassion, feeling, listening to others, talking to each other, and so learning to live with each other in more admirable ways. The current patriarchal systems of operating this world have failed, and so one needs to turn eyes toward feminist ways of living in this world. Teachers suffer, the students suffer too, and so does the world. Such feminist interventions challenge the structures currently operating and gradually transform them towards care, social justice, and a love-oriented world. This transformative approach is a process, not a temporary or quick-result-oriented project. It is a process of ‘who we are becoming’ with the possibilities of ‘who we might become.’

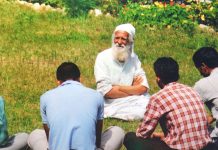

The teachers have to have their space of learning for themselves, teaching students, and being in constant dialogue with themselves and with the world. Dialogue has a strong potential to bring new knowledge and awareness that one might not expect. A teacher engaged in Dialogue makes space in the classroom for democratic and social justice education, where the possibilities of an equal and sustainable society lie. If schools are said to be the miniature of society, then it holds all the more potential to transform the ways of society. Children learning in such transformative- dialogue-oriented classrooms would become adults who have been Practicing Justice and Dialogue as keys to Peace.Teachers bonding with each other on the values of care, respect, empathy, and creating solidarities carries the humanistic revolution of the world where one changes the ways to be humane. Current patterns of education systems, heavily driven by political ideologies, are not helping the world, which is getting more polarized, violent, deceitful, and individualistic; the new vision would transform the praxis of the existing education system. What one needs to do is keep critical hope and keep working towards the vision. Amidst all challenges and pushes and pulls, one needs to build space to get into dialogue with people around, about transformation, about the possibilities that lie in caring for oneself and others, being compassionate with oneself and others, and taking these practices of empathy and compassion to the classrooms.

Nupur Rastogi is part of the Interest group for Dialogue, Fraternity, and Justice at Azim Premji University, Bangalore. Her research interest lies in understanding dialogue at the intersection of Power and Social Justice.