The first reported case of Coronavirus in India was on 30 January, 2020. It was almost two months later that the Indian government woke up to a reality that a few state governments were trying desperately to grapple with, to contain the spread of this virus. Even there, the arbitrary locking down of the country with no plan in place to help migrant workers reach their homes left us with heart-wrenching visuals and stories of despair and resoluteness. These were stories crafted by flesh and blood humans, those whom we tended to push to the margins of our consciousness. A self-righteous middle class was ready to blame these poor working people whose labour cushions their own lives for the spread of the virus. An absolutely foolish privileged section, literate in name only, was visible lapping up claims of astrological push-back of the virus through certain ritual and other performances. God men and charlatans have offered pills and remedies, suggested cow’s urine and other such fangled ‘medicines’ to counter the virus. There were still others, encouraged by a heartless and opportunistic political class that claimed there was no virus in reality; this was just a ploy by our external enemies to demoralize us and derail our economy. The rising number of cases from April to June, and then an apparent decline, a resurgence in September and again an apparent decline in December, misled even those of us who were following certain recommended protocols such as wearing masks, sanitizing hands and maintaining social distancing. Some of us began cautiously stepping out of doors, only to find to our amazement that there were huge crowds thronging the bazaars and the roads were chock-a-bloc. The arrival of the vaccines seemed to herald that we were now in the clear, and we gradually became more confident that the crisis could be tided over. Of course, a hugely hit economy was rearing to get back on its feet; people were restless; many of us had faced bereavements in the family but had not even been able to attend the last rites of our loved ones; the youth had been caged unnaturally for long enough. The situation was ripe for disaster. We are now faced with a second wave that is actually a tsunami – the result of the inability of our policy makers as well as the general public to heed the advice of the experts that were studying the virus and its many mutations.

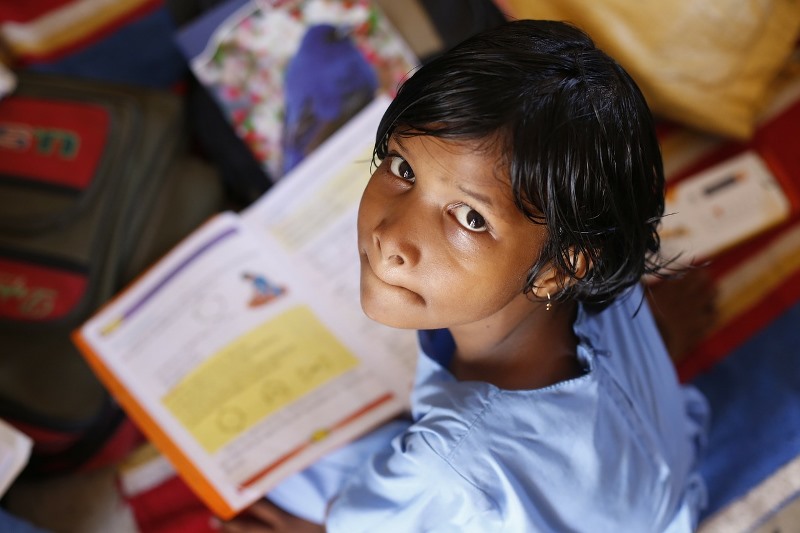

One of the few fields in which there was both continuity as well as a huge disruptive transformation, post-pandemic, has been education. Almost immediately after the pandemic was declared, educational institutions at all levels shifted to the online mode of instruction. There was again a lot of mismanagement, flip-flops on the evaluation patterns, duration of the semesters, etc. The very real issue of digital inequity, in the sense of the lack of connectivity and the impossibility of several students to buy or even access gadgets was raised from the start by the teaching community. Just when the possibility of returning to the classroom seemed on the horizon, we are back to square one. Many students have returned to residential campuses, while others in their homes are feeling the stranglehold of the lockdowns and curfews that have been declared in some states. Under the circumstances, we need to urgently think of how to tide through these times, yet again.

One of the first things is for our planners and administrators in educational institutions to be sensitive to the crisis, as it unfolds, instead of rigidly holding to their positions regarding examinations, semesters ending and the continuation of an academic calendar that is itself an ad-hoc creation. After all, the new admissions in higher education, across several institutions, only began their first semester six months or more after the normal schedule. While it is indeed very noble to not want students to miss a year, and hence cram three semesters in by December 2021, given the current situation, we need to prepare for the worst, if that is even possible given how grim things already are. I am among those who believe that academic engagement is one way of keeping ourselves afloat in these uncertain times. But perhaps we need to think of how to manage the academic requirements while keeping our sensitivities alive to other issues. Even as I write this, news of the passing away of a student’s father has come in. Emails have been pouring in from students about parents, siblings, friends, and they themselves testing positive for COVID-19. Some have reached out for help, not so much financial as for emotional support. A student mentioned that she sees herself engulfed into ‘nothingness’. I am frustrated by the blank screens that I speak to while lecturing; I can only imagine the sense of alienation that the disembodied voice through a machine engenders in a young mind. Women students write in their evocative social media posts about the lack of space literally and figuratively in their homes. Many have revealed shocking stories of sexual abuse within the home. Several have dwelt on their time being consumed by domestic chores. Indeed, for teachers the burden of the household, teaching, care-giving is something that gets too much. Until ten days ago, there were some institutions that were insisting that teachers come in person to oversee routine matters or attend meetings that could very well be done online. So, administrators, this is a wake-up call for you. Instead of being cussed, assess the reality, read and listen to the experts, and be reasonable on academic matters. It is also a reminder to ourselves as teachers that there is more to academics than lectures, textbooks and exams.

A second, important issue that needs to be addressed is mental health problems that several of us are facing. Studies in The Lancet and other journals and news magazines brought out by medical professionals suggest that there is excessive anxiety, depression, fear of loss and death, bottled-up grief and introversion among adolescents who see a very uncertain future for themselves. Of course, this is across professions, but it is particularly high among the age group located in educational institutions as students. The uncertainty of the future is one of the major concerns, and the socio-economic realities of the present aggravate their fears. For those on the margins financially, there may not be anything substantially new. But the middle class also feels itself shaken out of its cocoon – people have been retrenched, offices have been down-staffing and business closure stares at us all around, salaries have been cut, and even those in government jobs see the axe coming down with delays in disbursement of salaries and cuts in TA etc. The young adult is surrounded by these uncertainties, shares the worries of the parents and bread-winners. Is there anything that can be done under the circumstances? Experts from around the world say reach out to friends in groups; if you can manage zoom or other video calling apps – have singing sessions, yoga classes, gossip addas, even religious chanting if that helps. Students in my class have told me about the study groups they have formed informally to act as a support system, especially since they feel the institution has not bothered with them after giving them admission. Institutions must provide for online counseling by trained psychologists and sychiatrists. For parents, as I learnt the hard way, never ignore mood swings and try to break the silences before things get out of hand. Teachers especially have a huge role to play in the pandemic 2.0 – do not ignore distress calls. A student who writes or calls may often need just that little word of reassurance that we can give. And as far as our own needs go, let us reach out to each other, our friends and families, and yes, our students when necessary. We will possibly not ever get any acknowledgement of our contribution in these difficult times from the policy-makers and administrators who keep holding the Damocles sword of salary-cuts above our heads. But we are in a profession that demands this social responsibility of us.

Professor R. Mahalakshmi teaches ancient Indian history at the Centre for Historical Studies, JNU.