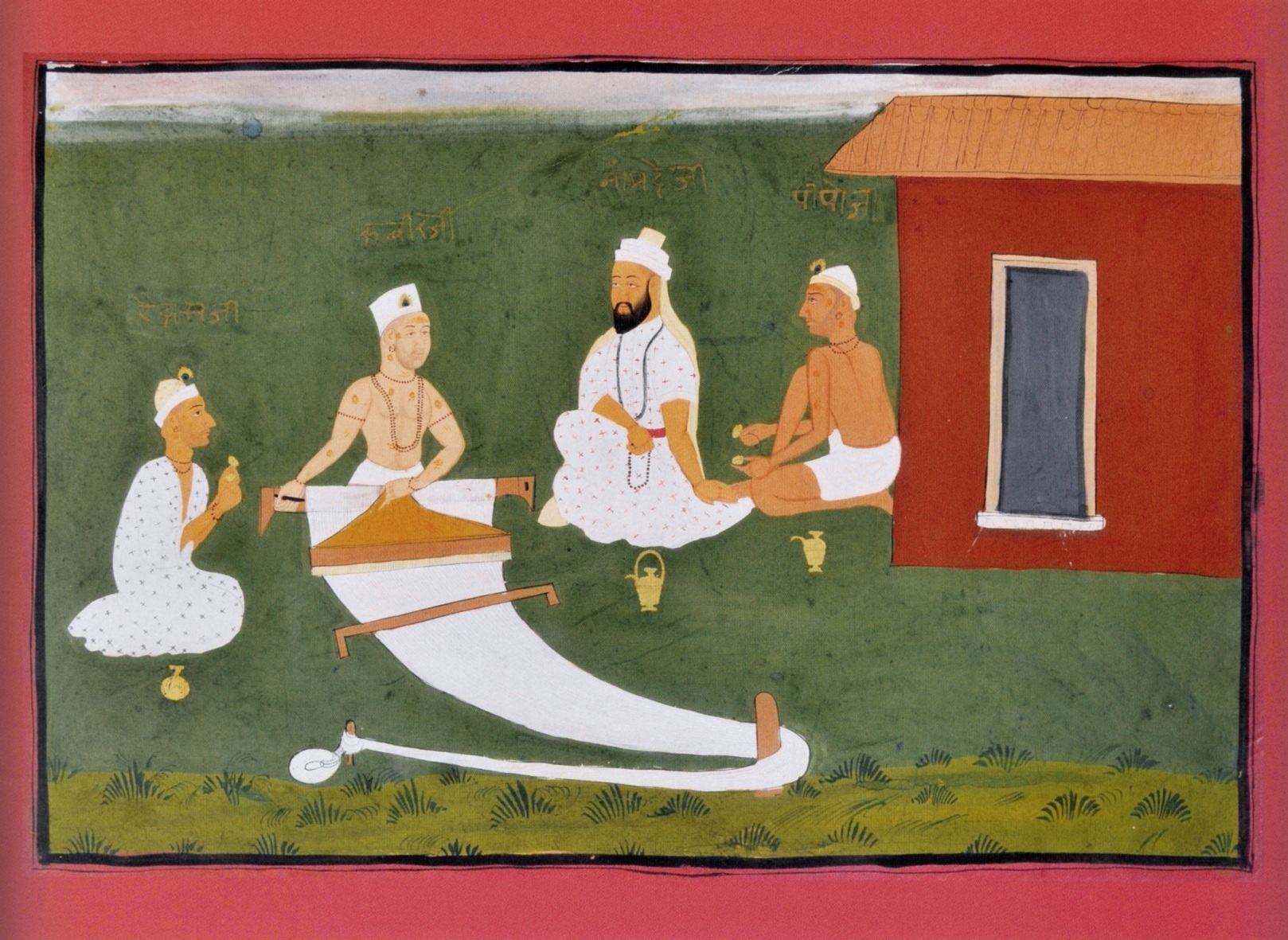

The Udyoga Parva of the great Sanskrit epic Mahabharata has one of the earliest references to the churning of the ocean. Surabhi, the mother of all cows, was born of the amrit (nectar of immortality) that was thrown out by the creator Brahma in the Rasatala, a region seven leagues under the earth. It is said that a single jet of her milk that fell on the earth resulted in a vast ocean being created – the Kshirasagara, or ocean of milk. We are told that the celestials – the devas, wishing to have the amrit, combined with their arch foes – the asuras, and churned the ocean using the strong Mandara mountain as their churning pole. The former, thus, obtained more than they had asked for: Varuni (an intoxicating drink), the goddess of prosperity – Lakshmi, the foremost among horses – Uccaihshravas, the best of gems – Kaustubha, and of course, amrit. In the Adi Parva of the same epic, we find further elaboration: the Mandara mountain was the ‘best of mountains’, brimming with lush vegetation, inhabited by majestic animals like the lion and elephant, and dotted by innumerable birds of various hues, singing their beautiful notes. The prince of serpents, who formed the bed of lord Vishnu, was commissioned to dislodge the Mandara, and use it for the churning pole. There was terrible destruction – the trees fell, animals were crushed, birds perished, and a dark cloud shrouded the entire resounding mountain. And all of this was for the greater good, because as a result of the churning, the sap of the trees which were hurtling into the ocean mixed with the milky waters creating thick clarified butter. Vishnu reinvigorated the tired devas whose spirits were flagging, and they continued to churn along with the asuras until finally, the first great element – the dull moon – with a thousand rays came out. He was followed by the beautiful shveta (white-clad) Lakshmi, Soma, the white celestial horse, the precious gem, and Dhanvantari, the bearer of the amrit. Finally, the great white elephant, Airavat, emerged from the ocean’s depths.

This myth is of great significance because it tells us about how the ancients envisaged creation and the order of things. The world is not just about the abundance of nature, it is about how to control what exists in nature. The various elements that come out of the ocean are the essence of this power to control nature. Lakshmi is described as radiant, with her white garments accentuating her purity. She symbolizes effulgence – that which shines and engulfs all in its radiance. Two other beings that emerged, the great horse and elephant, were meant to be possessed, symbolizing the importance of the domestication of wild animals in early societies. In fact, the two main things that the danavas (name for the asuras, meaning sons of Danu) staked a claim on in addition to the amrit were Lakshmi and Airavat. The mightier and more extraordinary the animals, the possessor would be considered mightier. The huge body, the white colour, were all meant to accentuate this sense of strength. Hence, the claim over the elephant by Indra, the ruler of the gods, was also a claim that he was the most powerful.

A second striking thing about the churning of the ocean was that along with the elixir, that which was life threatening also got thrown out of the ocean. The poison kalakuta was the final thing to emerge as a result of the churning. We are told that suddenly a blazing fire emitting terrible fumes engulfed the entire earth. Just the smell of it was enough to stupefy the entire universe. The juxtaposition of the amrit and kalakuta is not accidental; indeed, it is a deliberate playing upon the opposition of that which is life giving and that which can annihilate life. It is as if these were two sides of the same coin; or, as is typical in the brahmanical tradition, it represents a cycle, or even a loop, in which life and death are inextricably linked together. Related to this, we are directed to the idea that destruction and dissolution are at times inevitable, and in fact, necessary for birth and regeneration. It is immaterial that what was, may have also been good, or of value, as in the case of the mountain Mandara. Depicted as an image of perfect tranquility and abundance, it still had to come down, and the animals and birds living in that idyllic habitat had to be sacrificed. A new order, of necessity, requires the pulling down of the old. And the devas wished to exert their hegemony in the new order that the myth of the churning of the ocean projects. Thus, the majestic lions and elephants had to be sacrificed, and the devas assumed lordship over the heavens and earth.

Coming back to the issue of the kalakuta, another of the great gods, Shiva, being solicited by Brahman, swallowed that poison to save the world. He himself is said to have held the dark, deadly poison in his throat, which caused it to darken, and hence gained the title Nilakantha – the blue throated one. So while the devas were moved to act due to their self-interest, Shiva comes forward with no other motive but the preservation of the world.

Finally, an abiding idea in the myth is of the ends justifying the means. Thus, despite the fact that the help of the asuras is solicited for the sake of the churning, they are expendable once the deed is accomplished and the devas get what they want. The great gods come to the aid of the devas every now and then, ensuring that they succeed, and removing all the obstacles in their path. The asuras on the other hand, are strong, necessary to the cause, but also undeserving of their own hard-earned spoils.

On the eve of Dipavali, generally celebrated on the Naraka Chaturdashi (the 14th day of the month of Karthik in the Hindu calendar, marked in later mythology by the killing of a demon called Naraka), I cannot help but think that these ideas and symbols have a resonance beyond the time of their creation. They speak of the human endeavour, culture’s conquest of nature, partisanship and treachery, transcendence and the greater good, and that in the end, death is the leveler. All of these are as much today’s issues and concerns as they were in the past. But this is not a requiem for our times (or those), although darkness and destruction in recent times does appear to hover ominously over the idyllic spaces, be it the little world I live in, or the wider world outside. However, I would also like to think that with the waning at an end on the 14th day of the month, the waxing of the moon in the new month of Karthik heralds a new hope, that the light that ends the darkness, symbolized by the effulgent Lakshmi, will shine through. And that this Lakshmi belongs to us all, the danavas and devas.

Dr. R. Mahalakshmi teaches ancient Indian history at the Centre for Historical Studies, JNU.