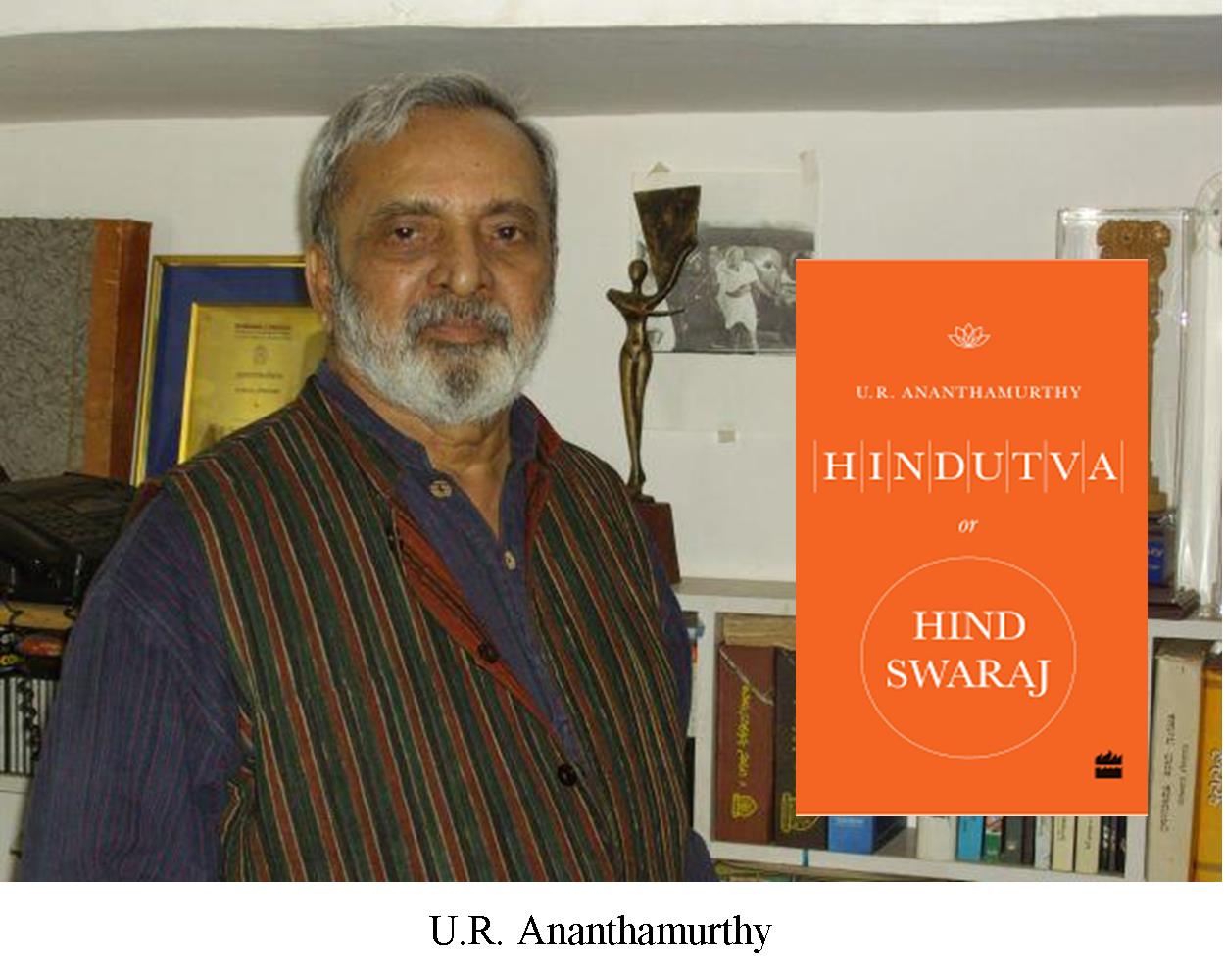

FROM THE BOOKSHELF

U.R. Ananthamurthy, Hindutva or Hind Swaraj , Harper Perennial, Noida, 2016

U.R. Ananthamurthy, Hindutva or Hind Swaraj , Harper Perennial, Noida, 2016

U.R. Ananthamurthy died on 22 August 2014. Hindutva or Hind Swaraj is his very last work. Keerti Ramachandra and Vivek Shanbhag have translated it from Kannada. There is no doubt that , as Shiv Visvanathan has indicated in the Foreword, this little book is written in a desperate hurry by an author who knew he was dying. Yet, here is a book that is courageous in spirit, and enlightens its readers; it reaffirms that Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj is a meaningful answer to Savarkar’s Hindutva.

Prof. Avijit Pathak teaches at the Centre for the Study of Social Systems, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

There is one hope. It is true that Lohia’s principles for the upliftment of Shudras ended up becoming Yadavized. And Ambedkar’s principles became Mayawati’s statues. The communists in Bengal have now lost their ground. In Modi’s enthusiasm for development , the atmosphere is further filled with factory smoke. Tribals who live close to nature have nowhere to go. In the hubris of extreme progress , man, suffering revulsion from excessive consumption, may see the need for change. If not, the Earth will speak.‛ – U.R. Ananthamurthy

What is the role of religion in modern/secular times? There seems to be no easy answer to this question. But one thing is clear. Religion doesn’t disappear; it manifests itself in multiple forms. From Emile Durkheim to Max Weber— the classical sociologists were preoccupied with this puzzle. Likewise, when we look at the political trajectory of a modern nation like ours we realize the gravity of this issue. To put it broadly, there are three approaches.

First, secular modernizers—guided by the ethos of liberal pursuits, or Marxian atheism or scientific reductionism—visualize a politico-cultural project dissociated from religion: its organization, belief systems and practices.

Second, there are cultural nationalists who seek to unite the idea of a strong/hyper-masculine nation and the ideology of the dominant religion as the cementing force.

And third, there are visionaries who cherish the spiritual essence of world religions, and try to create a society that humanizes modernity through the principles of austerity, ahimsa and soul-force.

U.R. Ananthamurthy’s book has come at a time when the proponents of the second approach—I mean the brigade of cultural nationalists with the ideology of Hindutva— have become immensely powerful. A great literary figure like Ananthamurthy— known for his deep engagement with Gandhian and socialist movements—was bound to be disturbed by this changing politicocultural landscape. He saw its ideological roots in Savarkar’s Hindutva project; he found Mr. Narendra Modi as its assertive champion; and he felt its ‘evil’ character—its violence, its reckless ‘development’ agenda, its insensitivity to our plural tradition, and its legitimization in the name of ‘national interest’. It stimulates the ‘middle class’s obsessive greed’. See his pain and anguish:

I attempt to see the evil that is within us and around us in its manifold avatars. The evil of our times are mines, dams, power plants and hundreds of smart cities. Shadeless roads, widened by cutting down trees: rivers diverted to fill the flush tanks of five-star hotels; hillocks, the abode of tribal gods, laid bare due to mining; marketplaces without sparrows and trees without birds.

Yes, the author is categorical in his condemnation of India’s move towards this ‘hubris’. To borrow his own words:

Modi , in his short-sleeved kurta, speaking with an uplifted chin, appearing as a dazzling leader, providing twenty-four hour electricity to corporates, is one of those pushing India towards that hubris. Everyone declares that Modi is not corrupt. That this has become a eulogistic refrain is a tragedy.

There is a close relationship between this greed-centric development and Savarka’s Hindutva project. Because it has got nothing to do with the spiritual ecstasy of religion. In fact, ‘like Muhammad Ali Jinnah, he was a rationalist who did not believe in religion’; he merely used it; it is nothing but the political appropriation of religion as an ideology of bounded nationhood. It is militaristic and hegemonic; it is exclusivist because, according to this project, to be truly a ‘Hindu’ or an Indian ‘it is not enough for India to be only a motherland, a matrubhoomi; it must become the holy land, punyabhoomi, as well’; it negates the spirit of plurality. As Ananthamurthy would say, ‘there is a flavor of fascism to it.’ No, Ananthamurthy is not a typical ‘secular’ modernizer with absolute indifference to the religious question. Instead, his deeply sensitive soul—touched by Carl Jung’s Answer to Job and Raja Harishchandra’s story—sees the significance of religiosity in the making of a spiritually regenerated/compassionate world. No wonder, he contrasts Savarkar’s Hindutva with Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj— a booklet attaching a new meaning to the spirit of decolonization, and revealing yet another project: an alternative modernity that sees religiosity as a thamurthy’s principle of love, ahimsa and sarvodaya, and strives for a moral order based on ecological principles, sustainable development, decentralization, austerity and deep empathy amidst pluralism. The following passage from the text makes this contrast pretty clear:

![]()

There is a significant difference in the way Savarkar and Gandhi wrote. Savarkar addressed his readers in a tone of heightened emotion. Gandhi spoke to them in an intimate manner. It is important to note that Gandhi’s work is in the form of a dialogue. Our ancient texts used a similar format, where the opposing viewpoint was set up as an adversary’s and then dismantled through argument. But Gandhi’s book does not do this. While one viewpoint is presented in opposition to another, the tone and tenor is that of a dialogue. In his writing, Savarkar sounds like an orator addressing a large Hindu community so that they forget their flaws and swell with pride in their love for the nation. However, Gandhi’s words are spoken in confidence, as if he speaks to just one listener. The speaker (Gandhi) reminds readers who are hasty in their thinking that in India’s freedom struggle, those who appeared slow movers were the ones who showed them the path of truthfulness.

In this context Ananthamurthy’s reference to Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment attracts the attention of the reader.

I would like to compare Raskolnikov (the protagonist) who lost faith in Christ because of his overarching ambition but regained it through anguish and love, with Godse, who recognizing the strength of Gandhi, assassinated him while he was on his way to pray to the Almighty for the well being of the country rather than his own. Raskolnikov had an inner voice which he despised but could not deny.Godse did not think like Raskolnikov. Through his readings of Savarkar, Godse, in his love for Bharat, truly believed that Gandhi, the advocate of non-violence was an impediment.

As one reads the text one feels the moments of despair. ‘It seems to me’ , Ananthamurthy writes, ‘the Gandhi era has come to an end; Savarkar has triumphed.’ And this despair gets intensified because , as he feels, ‘Modi, advocate of Hindu unity, with no regret for the Muslims massacred in Gujarat which he had ruled unopposed, has set out to make a strong India ruled by the corporates.’ Yet, the search continues. That is why, at this troubled time of narcissistic politics with an unholy alliance of Savarka’s Hindutva and neo-liberal global capitalism Ananthamurthy keeps pleading for Gandhi’s ‘egoless fearlessness’. ‘Had Gandhi lived’, the author convinces us, ‘he would have recommended Sarvodaya to a world that is gasping because of modern development.’

This article is published in The New Leam, JUNE 2017 Issue( Vol .3 No.25) and available in print version. To buy contact us or write at thenewleam@gmail.com