Poverty, like football, is universal. A truism that coalesced in the global popularity of Diego Armando Maradona, the “negrito” from the shantytowns on the periphery of Buenos Aires who became the centre of the footballing universe and, arguably, the greatest player of all time.

The Argentinian who died on 25 November 2020 at the age of 60 in Tigre, Buenos Aires Province, played the electrifying football of the gods while dancing with devils in a samba y caramba personal life rendered chaotic by claustrophobic fame, narcissism, self-destruction and excessive consumption of food, drugs, booze and women.

Yet, the political life of Maradona proved much more consistent. From El Pibe de Oro, the Golden Boy, the football-juggling street urchin who represented the aspirations of the so-called under-classes in deeply stratified Argentinian society, to the leftist friend of Cuba’s Fidel Castro and the enemy of Western imperialism in adulthood, Maradona stood with the oppressed.

In a world that became more brutally unequal during his lifetime, Maradona, who came from poverty, racism and injustice, stood with those still violated by the powerful. Those still haunted by the stench of being shat on.

This solidarity was recognised in Palestine, whose people and their suffering Maradona had claimed kinship with by declaring, “In my heart, I am Palestinian.” In 2014, when the Zionist state was laying waste to the Gaza Strip and her people during Operation Protective Edge, Maradona described Israel’s actions as “shameful”.

It was a solidarity recognised in far-away Bangladesh, whose masses took to the streets in indignation when Fifa banned Maradona from the 1994 Fifa World Cup after he tested positive for ephedrine.

It was also a solidarity born from experience. As a child, Maradona almost drowned in the communal shit of the violent and impoverished barrio he grew up in, Villa Fiorito. He was saved by an uncle, Cirilo, who gave him his first leather ball, which the three-year-old Maradona then took to bed every night for years.

These are the experiences of thousands of children in the Global South who dream of playing football for big European clubs or pray to escape penury with their lives intact. Some, like the African teenage footballers who are exploited every year and five-year-old Michael Komape, who drowned in a pit latrine at a South African school in 2014, do not escape life’s vicissitudes as Maradona did.

Maradona’s family home, a three-roomed shack for himself, his parents and seven siblings, had neither running water nor electricity. It barely kept the wind and rain out, despite the posters of former president Juan Perón and his wife, Eva, providing extra cladding for the home built by Diego Sr.

Maradona’s father was a factory worker descended from indigenous Guarani people and his mother Tota a descendent of Italian immigrants who comprised the second wave of European immigration to Argentina in the late 19th and early 20th century, the European poor looking for work in Argentina’s factories and fields.

Both were part of the Descamisados, the “shirtless ones”: the lumpen proletariat marginalised and derided by Argentina’s conquistador aristocracy, but whom the Peróns courted with their left-wing reforms and populism.

Standing up for the marginalised

In the chapter titled Maradona, Colm Tóibín’s contribution to the Picador Book of Sportswriting, the novelist recounts a 16-year-old Maradona’s 1976 meeting with Juan Carlos Cazaux, a representative of sportswear brand Puma, to discuss a sponsorship deal at the Sheraton Hotel in Buenos Aires.

Having heard of Maradona the previous year, Cazaux had initially been unimpressed with the stories. Talented kids from the poor barrios were a dime a dozen.

“But his informer insisted: this negrito is something else, you must come and see. The word negrito is important. In Argentina, it means someone from the social margins, from the shantytowns beyond the city, with Bolivian or Paraguayan blood, perhaps with Indian blood, but with darker skin than the ruling class. That was the word Cazaux first heard to describe Maradona.”

Cazaux would sign Maradona to Puma – a sponsorship that would continue until the great man’s death – for $50 000 over four years.

Fiorito’s inhabitants, Tóibín observed during a visit, had the darker skin of indigenous heritage, mixed marriages and labouring in the sun. The attitude of Buenos Aires’ bourgeoisie to the shantytown and its most famous son was reflective of a society deeply divided by race and class, Tóibín wrote: “In Buenos Aires, people are dismissive about Fiorito; they talk about its inhabitants in racist terms and mention Maradona’s Fiorito background as signalling a sort of reduced moral and intellectual fibre.”

Maradona had been cast as the interloper, the arriviste, a role that would stick to him, like shit on tattered cloth, throughout a brash, argumentative life during which he often proffered a middle finger or V-sign to the establishment.

These divides, between north and south, between the privileged who were determined to defend the status quo and the outsiders looking to break down neoliberalism’s doors and tear apart capitalism’s icons, would follow Maradona throughout his career.

This was especially so at Napoli, the southern Italian club to which Maradona transferred in 1984 after two turbulent years at Barcelona. The club had not won a scudetto (Italian league title) until the talismanic No. 10’s arrival in 1984 heralded an unprecedented period of supremacy that brought in two Italian league championships, the Italian Super Cup, the Coppa Italia and the Uefa Cup.

A city that had been derided by the rich north – from medieval to modern industrial times – as a place of pestilence, disease and poverty, with inhabitants considered racially inferior, would, like Argentina, find her redeemer.

As writer and journalist Eduardo Galeano describes in Soccer in Sun and Shadow, Maradona’s upending of the north’s supremacy over the south delivered to him a reverential deification. “Later on in Naples, Maradona was Santa Maradonna, and the patron saint San Gennaro became San Gennarmando. In the streets they sold pictures of this divinity in shorts illuminated by the Virgin or wrapped in the sacred mantle of the saint who bleeds every six months. They even sold coffins for the clubs of northern Italy and tiny bottles filled with the tears of Silvio Berlusconi.

“Kids and dogs wore Maradona wigs. Somebody placed a ball under the foot of Dante, and in the famous fountain Triton wore the blue shirt of Napoli. It had been more than half a century since this city, condemned to suffer the furies of Vesuvius and eternal defeat on the soccer field, had last won a championship, and thanks to Maradona the dark south finally managed to humiliate the white north that scorned it.”

The battle between the Global North and the Global South also swept Maradona and his turbulent imagination into a space of sanity and relief. It would lead to Maradona’s anti-imperialist essence being expressed in the football stadium and on the streets.

On the pitch, there was no greater example of sticking it to the traditional Western powers than in 1986, during the World Cup quarterfinals against England when Maradona scored two goals to knock them out of the tournament.

The first was scored with the right hand, the second with the left foot after a sublime 10.6 seconds when Maradona beat more than half the England team to score the Goal of the Century.

The first goal Maradona described as being scored by the Hand of God, suggestive of the divine retribution that the English deserved after killing Argentina’s young sons during the war over Las Malvinas (the Falklands) in 1982.

In his official biography, El Diego, Maradona says, “In the pre-match interview we had all said that football and politics shouldn’t be confused, but that was a lie. We did nothing but think about that. Bollocks was it just another match!”

But, as Martin Amis writes in his essay In Search of Dieguito, the victory wasn’t just about Las Malvinas, “it was to be the historic revancha of a subjected and immiserated population”.

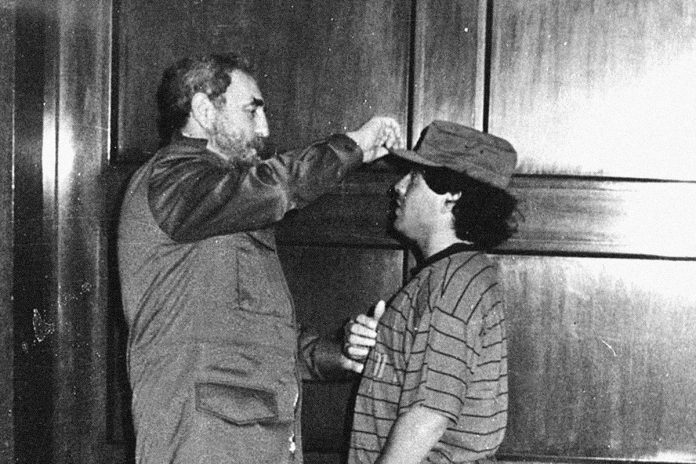

Falling in love with Castro

The left-wing Maradona found kinship with another global darling from Argentina, Che Guevara, whose tattoo he sported on his right arm, because “it was time the two greatest Argentines were united in the same body”.

He befriended progressive leaders of Latin America who were intent on redistributing wealth in their countries, including Eva Morales in Bolivia and Hugo Chavez in Venezuela.

But it was Cuba’s Fidel Castro, who had invited Maradona to Havana to kick his cocaine habit while being tended to by the president’s personal physicians over four years at the turn of the millennium, that Maradona revered as his “second father”. Castro and Maradona would die on the same day four years apart.

In My Life, Castro, whose face was tattooed on Maradona’s deadly left leg, remembered Maradona’s participation at the demonstrations against then United States president George W Bush and his country’s proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) at the Summit of the Americas in Argentina’s Mar de Plata in 2005.

At the time of the gathering, revelations had emerged in the US that the Bush administration had lied about the nuclear threat posed by Saddam Hussein’s Iraq before its 2003 invasion of the country. This led to heightened anti-imperialist sentiment in Latin America and around the world.

At the protest, attended by Nobel Peace laureate Adolfo Pérez Esquivel and what Castro described as the “creme de la creme” of Latin American revolutionaries, Maradona wore a T-shirt casting Bush as a “war criminal”.

“They gave an unforgettable lesson to the empire,” Castro observed, “as they defeated the FTAA on the streets.”

This was vital, said Castro, because the FTAA “sought to open the borders of all the countries [in Latin America] that have a very low level of technological development to the products of those countries that have the highest level of technological development and productivity, those who build the latest-model aeroplanes, those who dominate worldwide communications, those who want to get three things from us: raw materials, cheap labour, customers and markets – a new form of ruthless, savage colonialism”.

Alfredo Tedeschi, an Argentine television producer who became close friends with Maradona during a stint working for Reuters in Havana during the early 2000s, recently told the news agency that Maradona’s “humble beginnings” ensured “Castro was his idol”.

“It was like he fell in love [with Castro], and then came Chavez, Morales and the rest,” said Tedeschi.

Tedeschi recalled the time Maradona knocked on his door and proposed a spontaneous visit to Castro. The Cuban leader received them within minutes of their arrival and cleared his busy agenda to spend three hours with them, including to play football in his office.

“They would always talk about politics, Diego was really interested in politics,” said Tedeschi, adding that Castro would pay spontaneous visits to his Havana home.

Maradona interviewed Castro on his Argentine television show in 2005, asking how George W Bush had been re-elected president of the US, to which Castro responded: “Fraud. The terrorist mafia of Miami!”

During an appearance on Chavez’s weekly television programme in 2007, Maradona said: “I hate everything that comes from the United States. I hate it with all my strength.”

This is perhaps understandable considering the young Diego, who signed his first contract for Argentinos Juniors at 15 years old and made his international debut at 16, reached adulthood when the violent military junta that had taken control of Argentina in 1976 was extending the bloody use of its security apparatus on its own people, with support from the US Central Intelligence Agency.

The significance of the 1986 World Cup win

The junta’s Process of National Reorganisation led to the Guerra Sacia, the Dirty War, a state-perpetrated terror that clamped down on left-wing insurgents and saw about 30 000 people – clergy, students, trade unionists, political activists, ordinary workers, mothers, fathers, sons and daughters – disappear.

The US backed the reign of terror, as it did similar bloody ruthlessness in Chile, Nicaragua, Venezuela and other parts of Latin America. Maradona was incapable of not hating the yanquis.

Argentina’s 1978 World Cup victory on home soil was dogged by allegations that the military junta had intervened in matches to ensure a home victory that would drive the nation’s attention away from the Guerra Sacia.

Never properly acknowledged or celebrated by people traumatised by the loss of loved ones, it made the country’s Maradona-led victory in Mexico in 1986 all the sweeter, and more profoundly felt. More important to Argentinians. More theirs.

Argentina is a country crippled by successive economic collapses linked to the International Monetary Fund’s structural adjustment programmes. It is where the rich live, as Tóibín observed, in a state of “spiritual and cultural exile”, turning their noses up at those less fortunate and sniffing towards Europe.

Brash, loud, swaggering and divinely talented Maradona punched those noses. Made them bloody. In doing so, he became the redeemer of the Argentinian masses.

Galeano described Maradona as football’s “most strident rebel … He wasn’t the only disobedient player, but his was the voice that made the most offensive questions ring out loud and clear.”

These included asking Fifa why players were subjected to the dictatorship of television during the 1986 World Cup when they had to play in the midday sun for European audiences. And for the sport’s governing body to open its books for public examination, especially by the players, the performers on whose backs billions of dollars were flowing into the sport from advertising and television broadcasting rights revenue.

He sought to have these questions answered when he set up the International Professional Players Association with the likes of Liberia’s George Weah and France’s Eric Cantona. The aim, Maradona said at the union’s launch, was to leverage their fame to help impoverished footballers lower down the sport’s rungs.

This was because Maradona was a worker. He became a worker when he signed that first contract at Argentinos Juniors. Despite his father continuing to labour in the mill, Maradona became his family’s main breadwinner, his first contract had a rented apartment for his family written into it. He bore the responsibility of being his family’s first son after four daughters.

His move to Boca Juniors, the club of Buenos Aires’ working class, confirmed Maradona’s popular appeal.

His maverick talent also confirmed Maradona’s body as the site of violence and attempted subjugation, Galeano’s “the body as metaphor”. His became a metaphor for the experience of the downtrodden in Argentina, South Africa, Latin America, Africa…

In the public diary he kept in sports newspaper El Grafico while playing in Argentina, a teenage Maradona once wrote simply: “All my rivals want to kick me.”

With his technique and trickery learnt in the potreros of Villa Fiorito, a natural speed of mind and body, and an extravagant, supernatural footballing vision, Maradona was often uncontrollable. Because of this he suffered an unprecedented violence throughout his career, which only made the masses identify with and love him more.

He bore their pain. He bore the scars from a violence meted out by those who sought to defend the status quo, entrench inequality and shut out the upstarts – on the football pitch and in life.

Niren Tolsi is a freelance journalist whose interests include social justice, citizen mobilisation and state violence, protest, the Constitution and Constitutional Court, football and Test cricket.

This article was first published by New Frame.