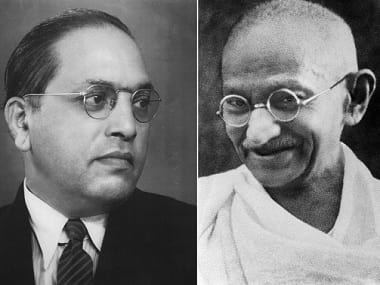

Inspired by Babasaheb Ambedkar and the U.S. Black Panthers, the 1970s saw a rising consciousness of the young Dalits in Bombay in the form of Dalit Panthers movement for addressing injustices by holding the perpetrators of oppression against the Dalits accountable.

The term ‘Dalit’, meaning oppressed or broken, was revived by the Panthers to be expanded to meaning scheduled tribes, poor peasants, women and all those being exploited in political, economic, and religious fronts.

Within this social force, the term ‘Dalit’, stripped of its earlier impositions of pollution, came to be seen as beyond caste- as and assertion for change and revolution.

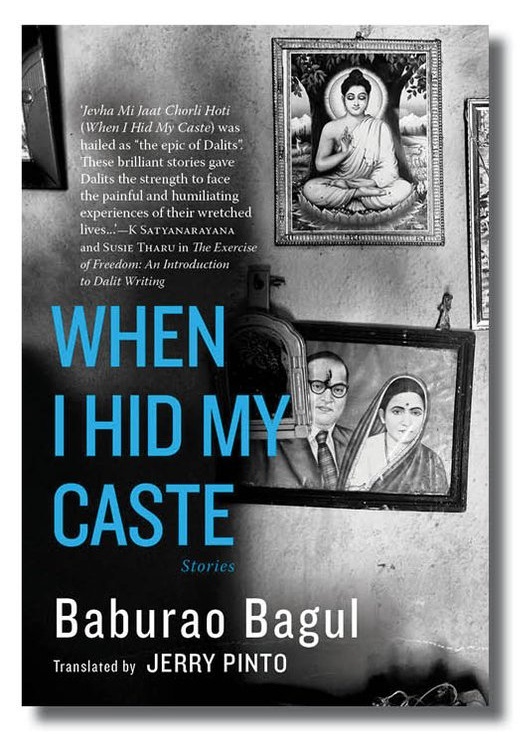

In this stirring social climate, Baburao Bagul, one of the pioneers of modern Marathi and Dalit Literature, published his first collection of short stories- Jevha Mi Jaat Chorli Hoti (When I hid my Caste) in 1963. The intense force and radical realism of the stories in this debut collection revolutionized the literary scene in Maharashtra and is hailed as the “epic of Dalits”.

Jerry Pinto has been reckoned for bringing in the nuanced and empathetic translations of historic Marathi literary work starting with Daya Pawar’s Baluta (2015), Malika Amar Shaikh’s memoirs Mala Udhvasta Vhayachay (I Want to Destroy Myself), Cobalt Blue by Sachin Kundalkar, Vandana Mishra’s autobiography Mee Mithaachi Baahuli (I, The Salt Doll), and Khidkya Ardhya Ughadya (Half-Open Windows) by Ganesh Matkari.

Adding to his formidable repertoire for introducing the English readers to hallmark regional literature, When I Hid my Caste (2018) is his important work in the recent times.

Bagul’s stories in the collection shake the readers with the raw intensity of the life at themargins. He exposes the pain and horror of the lived everyday experiences of caste that has been erased from the upper castes’ collective consciousness.

Bagul’s story demand the audience to acknowledge the revolt, pain, and dissent of the marginalized by bringing forth the complexity of the socio-cultural forces that have shaped the world. Infused with the storm of Marxist ideals and Ambedkar’s Buddhist way of living, Bagul’s characters embody the humanist nature which is neither black nor white, pure nor perverse, and hurtle towards an end which is often tragic and sometimes victorious.

Using the language of affect over reason, the characters’ stories emerge as sounds of experiences over causality. Through the everyday ordinary lives of slum dwellers, sex workers, gangsters, and rebellious youth, Bagul brings forth the conception of caste as immutable in time, in the immediacy of an experience that is embedded in their routine and their repeated participation in the day to day chores.

In ‘Prisoner of Darkness’, Bagul’s expressionist language reaches out with compassion to Banoo, the kept woman and his son, both victims of the social circumstances. He brings to front the ugliness of caste which makes the upper caste women to become oblivious to the sufferings of the lower caste women by ‘othering’ them.

The language of affect by Bagul serves to create the horrific experience of caste as well for enforcing revolt and dissent through use of verbs that carry physical force of violence. Bagul’s character in ‘Gangster’, an Ethiopian migrant, carves the story using his rage as he ‘pounds the ribcage of the staircase’, having ‘massive bull-like heads and fists of iron’. The creative use of language by Bagul through aggressive clauses, unveiling the violence of the characters, the physical description of the bodies with images of strength, endurance, and dark, frightening beauty enforce the anger, the dissent, and the assertion of the marginalized to fight against the violence and humiliation felt at the hands of the upper castes.

In ‘Dassehra Sacrifice’, the sculpted beauty of Deva’s muscular body that overpowered the might of the bull, and Damu’s arrogant defiance of the upper caste domination with his ‘six- foot, warrior, and adamantine coloured body’ in ‘Bohada’ pay reference to this vivid description of assertion of lower caste men.

Bagul’s compassion in the depiction of the life of women in ‘Streetwalker’ and ‘Competition’ is filled with pain inflicted by the violence of the social environment, rendering naked powerlessness of their positioning. In one of the titular story, ‘Revolt’, Bagul exposes the stomach churning horror of caste system through the experience of the protagonist, whose caste violently enforces him to lift human excreta. The revulsion and hatred of Jai, the shame and pain of his mother, and the indifference of the surrounding crowd, which Bagul remarks that their minds has been murdered long ago by Manu, hits the readers hard and pricks the consciousness for the participation in an inhumane social order.

In the title story, ‘Why I hid my caste’, the unnamed protagonist, arrives in the town where his employer, the railways, has posted him. The story wrapped with the angst, anxiety, and the anger of the protagonist keeps the readers on toe fearing the tragic end that awaits at the revealing of

his caste. In the end, when the protagonist is lynched by his colleagues, he says, “When was I beaten by them? It was Manu who thrashed me.” Here, the caste structure springs out of the clutches of the teleological time and emerges immutable even in the face of modernity and the changes it promises to bring.

Bagul’s remarkable art of storytelling and his characters take the readers along in a desperate search for humaneness in a society that is entrenched with inhumane caste practices. Even after passing of decades, the story remains relevant to the present, as an experience of the ordinary day to day life of the people at the margins.

Through the brute honesty of his prose, Bagul tears open the consciousness of the privileged main stream and floods it with empathy by making them uncomfortable of their own negligence of the unacknowledged alternate reality.

Translating a piece of literature which is heavily embellished with events, selves, objects, and experiences, laced with symbolic significance that gives them agency, has to be continuously

Investigated and deciphered. Jerry Pinto’s vivid and empathetic translation, retaining the original work’s ‘mode of signification’ surely serves to impact the consciousness of the English readers.

Bagul’s story asserts the primal importance of literature to act as moral and political enabling force as he remarks in the essay in Marathwada, ‘Dalit Literature believes that looking for the meaning of life in social debates, philosophy or political manifestos would make it monochromatic. The meaning of life is to be found in nature. Man is the very embodiment of nature.’ Through this translation, his characters and their stories will become alive and illuminate the literary world once again.