A nation’s culture resides in the hearts and in the souls of its people. This culture grows from the depths of their actions and the greatness of their aspirations but often amidst external influence the people are unable to acknowledge their own potential in constructing a culture that has the flavour of civilization. Nirmal Kumar Bose’s revealing account in ‘My Days with Gandhi’ looks at this question poignantly.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]here was a packed audience during prayer time, which listened to Gandhiji without the slightest disturbance. He explained once more the reason for postponement of his visit to Noakhali and his intention of staying in the present place. Let them not think that the parts of Calcutta which were deserted by their Hindu inhabitants and were occupied by Muslims were being neglected. They were working for the peace of the whole of Calcutta and he invited his audience to believe with them that if Calcutta returned to sanity and real friendship, then Noakhali and the rest of India would be safe. News began to reach our camp towards evening that a strange thing had started in different parts of Calcutta. For one whole year, ever since the beginning of the Muslim League’s Direct Action on the 16th of August 1946, Hindus ‘and Muslims had strictly avoided one another’s company.

Transference of population had taken place, so that Calcutta had virtually become divided ·into exclusively Hindu and Muslim zones. But news began to pour in now that the Hindus and Muslims were both coming out in the streets, embracing one another and the latter were even inviting their erstwhile enemies to visit their masjids. It reminded me personally of what I had read in Eric Maria Remarque’s. All Quiet on the Western Front, when on Christmas Eve, the common French and German soldiers came out of their trenches and forgot, even if it were for a brief moment, that they were to regard each other as enemies I left in a jeep and passed through some of the most affected quarters and witnessed an upsurge of emotional enthusiasm which somehow rang untrue; for to my mind it was a reaction against the inhibitions of a war through which the citizens had been passing for one whole year.

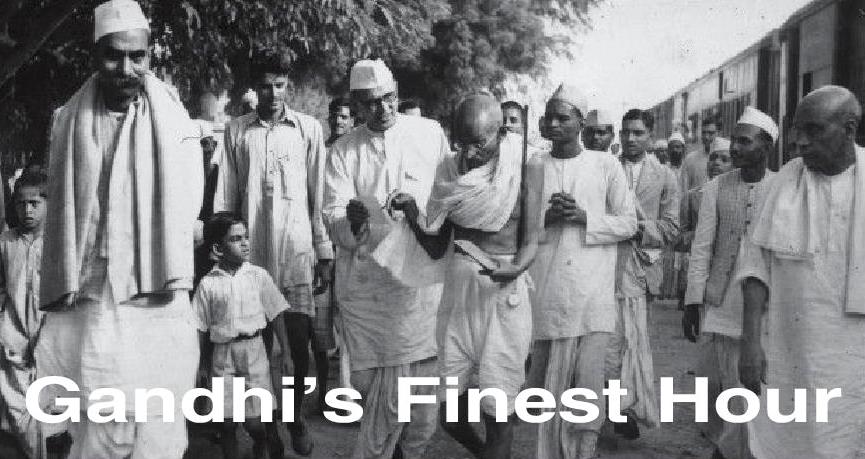

Gandhiji wished to observe the demonstration himself and he was therefore driven in a closed car as he sat between two or three passengers, so that people might not recognize him and out of enthusiasm make it impossible for him to proceed. Beleghata, Friday, 15-8-1947: Gandhiji had started a one day fast in observance of the day of deliverance of India. The new Governor of this province, C. Rajagopalachari, paid him a respectful visit and congratulated him on the ‘miracle which he had wrought.’ But Gandhiji replied that he could not be satisfied until Hindus and Muslims felt safe in one another’s company and returned to their own homes to live as before. Without that change of heart, there was likelihood of future deterioration in spite of the present enthusiasm.

At 2, there was an interview with some members of the Communist Party of India to whom Gandhiji said that political workers, whether Communist or Socialist, must forget today all differences and help to consolidate the freedom which had been attained. Should we allow it to break into pieces? The tragedy was that the strength with which the country had fought against the British was failing them when it came to the establishment of Hindu-Muslim unity. With regard to the celebrations, Gandhiji said, ‘ I can’t afford to take part in this rejoicing, which is a sorry affair.’ There was then a half-hour interview with some students of Beleghata to whom he explained in detail why the fighting must stop now. We had two States now, each of which was to have both Hindu and Muslim citizens. Students ought to think and think well. They should do no wrong. It was wrong to molest an Indian citizen merely because he professed a different religion. Students should do everything to build up a new State of India which would be everybody’s pride. With regard to the demonstration of fraternization he said, ‘ I am not lifted off my feet by these demonstrations of joy.’ –

There was a great rush of visitors all through the day ; and every time a large number gathered in the garden and the open lawns attached to the house, Gandhiji stepped up to the window of his room and stood with folded hands returning the salute of the multitude. At the prayer meeting to which Gandhiji walked on foot, the rush was very great. And what could have been done in five minutes’ time took twenty minutes to cover. Gandhiji referred to Lahore from where sorry tales of rioting had been reaching him every day and said that if the noble example of Calcutta were sincere, it would affect the Punjab and the rest of India. There was also a reference to Chitta-· gong which was now in Pakistan but where floods had recently caused severe damages. Were the two portions of Bengal to treat one another as foreigners? Nature’s floods were no respecter of persons or of political divisions between man and man. Hindus and Muslims were equally affected thereby.

On the 16th, Rev. John Kedlas, Principal of the Scottish Church College, came to see Gandhiji with some members of his staff. The chief question discussed was the relation between education and religion. Gandhiji was emphatic in his opinion that the State being secular, it could never promote denominational education out of public funds. Incidentally he said that although India had discarded foreign power it had not discarded foreign influence.

Sources: My Days with Gandhi, Nirmal Kumar Bose