By Laura Hood, The Conversation

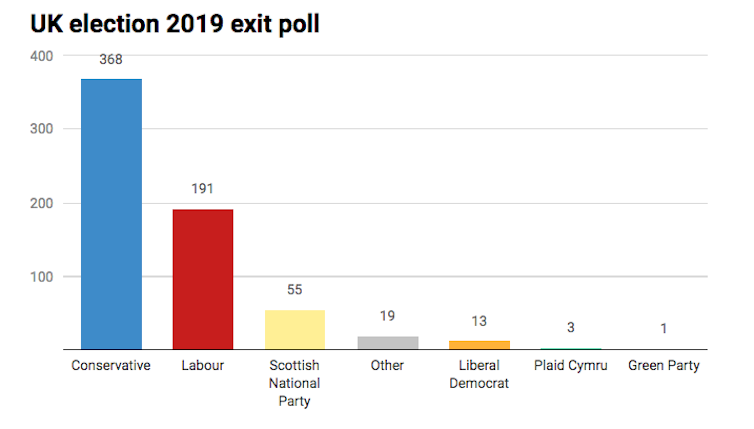

Results are still coming in but Boris Johnson is now confirmed to have secured a big victory in the British general election. He went into the poll at the head of a minority government and has emerged with a significant majority. With just a few seats left to count, his Conservative Party holds 362 seats in the 650-seat Westminster parliament.

The Labour Party has suffered its worst loss in decades – and its fourth general election defeat in a row, ending up with 203 seats. The Scottish National Party looks to have made significant gains in Scotland. That would now appear to strengthen the case for a second Scottish independence referendum, posing another huge constitutional question for the UK.

While the polls had generally pointed towards a victory for Johnson, it had been predicted to be small and a hung parliament looked like a possibility according to some pre-vote opinion polling. So how did the UK come to this decision and what happens now with Brexit? Over the campaign, academic experts have been analysing the policy platforms of each party and can shed light on the current situation.

Brexit is go …

Johnson’s majority puts him in a position to comfortably pass his Brexit deal through parliament after several years of stalemate. He can now be expected to plough ahead at speed, given that all his parliamentary candidates agreed to support the deal’s passage through parliament ahead of the election. His plan is to leave the EU by January 31, 2020.

This is therefore a good moment to read over what exactly that deal entails. In brief, it is a relatively hard form of Brexit – although whether it will stay that way is up for debate now that Johnson has such a significant majority and potentially the freedom to soften his position. Under the current plan, though, the UK will leave the single market and customs union, ending free movement with a plan to introduce a points-based immigration system. But there remain questions about potential trade friction between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. All this was outlined by Oliver Patel, research associate at the UCL European Institute, who combed through the documents a few days before the vote.

Patel looked ahead to the next stages too, since departure marks the beginning of an intense period of negotiations with Brussels. He noted that there is much still to be agreed – and on a tight timetable.

The UK and the EU have between the withdrawal date and December 31 2020 (the end of the transition period) to negotiate and ratify the full agreement on their future relationship, which should govern relations in a vast range of areas such as trade, migration, security, foreign policy and data.

… but Brexit is not ‘done’

It’s hard to deny that this election appears to have been won at least partly because of one promise – that Johnson will “get Brexit done”. He repeated his three-word mantra over and over again, at every opportunity. But as multiple experts have pointed out in recent weeks, this is an optimistic take. Even if Johnson does meet his self-imposed deadline of January 31, the story is far from over.

Helen Parr, professor of history at Keele University’s school of social, global and political studies, sees a long road ahead, and one that could still end in what is effectively a no-deal Brexit.

The reality is that government resources will be tied up on Brexit for the foreseeable future. Equally, the idea that the UK will be free to do as it pleases the moment the withdrawal bill passes through the House of Commons is an illusion. Rather, Britain will find its freedom of action constrained by what sort of future relationship it can agree with the EU and other trading partners. Those questions will take years to answer, if they are ever satisfactorily resolved.

Johnson has ruled out extending the transition period so if sticks by that and then can’t strike a trade deal by the end of 2020, the UK may depart without one.

A new political identity

This election has dramatically redrawn the electoral map in the UK. Chunks of the country that have traditionally been considered Labour strongholds have turned Conservative. This is a switch of allegiances that would have been considered unthinkable just a few years ago.

But as Geoffrey Evans, professor in the sociology of politics, at the University of Oxford, revealed, political identities in the UK are now as often defined by your position on Brexit as by which party you support. He has conducted surveys charting this shift in the years since the 2016 referendum and watched as people steadily change to prioritise their Brexit identity.

Tellingly, even in mid-2018, two years after the referendum, only just over 6% of people did not identify with either Leave or Remain. Compare this with party political attachment, where the percentage with no party identity increased from 18% to 21.5% over same period – in part due to the decline of UKIP. Only one in 16 people don’t have a Brexit identity whereas more than one in five have no party identity.

This election is arguably the culmination of this process. So many voters in Labour’s so-called “red wall” in the midlands of England and northern England appear to have voted in a way they probably wouldn’t have countenanced just five years ago, delivering the biggest Conservative majority in years.

What went wrong for Labour?

This loss will certainly force some deep soul searching within the Labour Party. Its leader Jeremy Corbyn opted to fight this election on an ambitious platform of reform, pledging to nationalise utilities and even offering free internet access for all. He proposed a radical green agenda that would have put the UK miles out ahead of other nations while Johnson didn’t even bother turning up to a debate on climate change. So how could such a bumper package deliver such a dismal return?

Labour will need to look particularly closely at the working class voters it has lost in the country’s former industrial bases. David Etherington, professor of local and regional economic development at Staffordshire University explored the party’s recent history with these supporters and found its approach lacking. Years of decline, followed by the financial crash of 2008 left many people in these “left behind” regions wanting change. And many saw their opportunity in 2016:

In the absence of a coherent alternative to austerity and, more importantly, a previous lack of active engagement by the Labour Party with its core electorate, a vote to leave the EU was a vote for change. And for some it was as an expression of protest.

Labour has struggled for years to define its position on Brexit. Even though it has more recently solidified its stance, pledging a second referendum, it also sought to make the 2019 election about anything other than Brexit. There will certainly now be questions about whether these were the right decisions.

Is Scotland on the way out?

The Scottish National Party surge leaves it in charge of nearly every constituency in Scotland. The nationalists have put calls for a second independence referendum at the centre of their campaign. As William McDougall, Lecturer in Politics at Glasgow Caledonian University, explains, first minister Nicola Sturgeon is capitalising on anti-Brexit sentiment to push for another go at breaking away from the United Kingdom:

The reason why support for independence has risen is perhaps that a section of Remain voters have switched sides: the SNP’s Remain credentials help the party to distance its brand of civic and cosmopolitan nationalism from the anti-EU, anti-immigrant nationalism that we see in a number of countries. As a result, the pro-independence vote which was already largely pro-EU is now even more solidly in favour of Scotland staying in the EU.

A strong Conservative majority in Westminster certainly makes it hard to see how another independence referendum would actually come about, but for now, a big statement has been made in the shift towards Sturgeon’s party.

Who is Boris Johnson, really?

Johnson has been prime minister for a few months already but he can be a tricky character to pin down – especially when he’s hiding in fridges. Chris Stafford, a doctoral researcher at the University of Nottingham, gave it a good go when he first took office, painting by numbers to find the man beneath.

From his chequered 14-year career in journalism to his tenure as London mayor, during which time he showed a penchant for vanity projects, Johnson has made some surprising choices in his various careers.

But this all appears to have been priced into the 2019 vote. Johnson is regularly accused of hiding who he really is, but maybe that’s not actually the case at all. He has left enough clues along the way for us to build a picture of the man he is – and the British public has decided they are fine with it.![]()

Laura Hood, Politics Editor, Assistant Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.