Advertisement

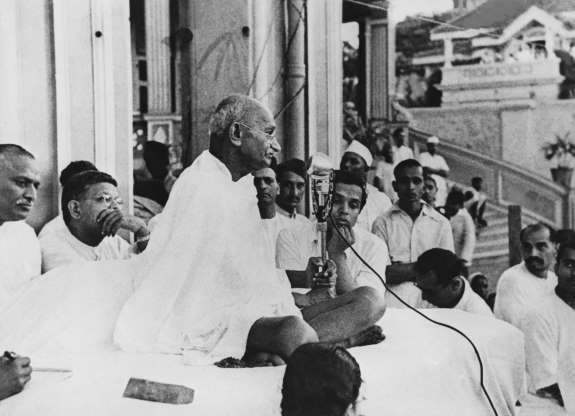

The final week of the Mahatma’s life was rich with symbolism redolent of India’s unity. On 23 January 1948 Gandhi was ‘very glad’ to take note of Subhash Bose’s birthday, even though he ‘generally did not remember such dates’ and ‘the deceased patriot believed in violence’, while he was wedded to non-violence. Bose, according to the Mahatma, ‘knew no provincialism nor communal differences’ and ‘had in his brave army men and women drawn from all over India without distinction and evoked affection and loyalty, which very few have been able to evoke.’ A lawyer friend had requested Gandhi for a good definition of Hinduism. He did not have any, but suggested that ‘Hinduism regarded all religions as worthy of all respect’. Bose, according to him, was ‘such a Hindu’ and so, ‘in memory of the great patriot’, he called upon his countrymen to ‘cleanse their hearts of all communal bitterness.’

For Gandhi’s generation 26 January was Independence Day. ‘Let us permit ourselves to hope’, he said on that occasion, ‘that though geographically and politically India is divided into two, at heart we shall ever be friends and brothers helping and respecting one another and be one for the outside world.’ The next day he was taken inside the sanctum sanctorum of Chishti’s shrine in Mehrauli where he was anguished to see the damage to the exquisite marble screens. He had come to make a pilgrimage, not a speech, and simply urged Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs to ‘never again listen to the voices of Satan and abandon the way of brotherliness and peace’.

On the morning of 30 January 1948, Gandhi did not neglect to do his daily Bengali writing exercise even though he had other pressing work, such as drafting a new constitution for the Congress. The sound of the shots fired at the Mahatma that evening by a Hindu fanatic echoed across the length and breadth of this great land. ‘The last few months of Gandhiji’s life and the manner of his death,’ B.R. Nanda wrote,’ constituted an epic struggle between an all-embracing humanism and sectarian fanaticism.’

A seventeen-year old girl as attending an interregional and inter-caste wedding of a Bengali bride and Malayali groom in Calcutta that evening when she heard the stunning news that Gandhiji had been shot dead. She tried to persuade herself that it must be a rumour. A pall of gloom slowly descended on the gathering and the guests quietly departed. Returning home, she heard the radio playing the song ‘Samukhe Shanti Parabar’ as the great soul began his journey across the ocean of peace. Sarat Bose loved English literature and Shakespeare as much as he had hated British rule. On receiving the heart-rending news that the Mahatma was no more, he remarked wistfully, ‘When comes such another’—he might have added, if ever another.

Source : Sugata Bose, The Nation as Mother and other Visions of Nationhood, Viking, 2017