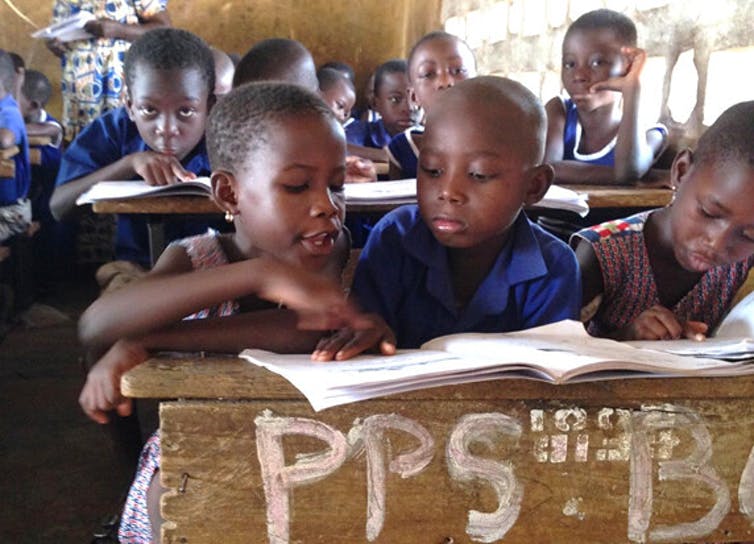

More than 46 languages are spoken in Ghana. As with many other countries on the continent it is struggling to find an effective policy for language in education. At present Ghanaian children are taught for the first five years of school in their own language while they are gradually exposed to the the English language, before shifting to English as medium of instruction in the upper primary and beyond.

Using a bilingual (Ghanaian language and English) methodology, the country is implementing a policy to promote teaching pupils in kindergarten through primary grade three to read and write in their local language – one of 11 selected Ghanaian languages – while introducing them to spoken English, and by

grade two, to written English.

The approach is designed to be a transitional one in which local language literacy is used as a bridge to English literacy. The programme also serves to encourage and celebrate the use of local languages as a valuable aspect of Ghanaian culture.

However, many parents and education officials continue to agitate for English to be used as the medium of instruction from the start.

The history

There is plenty of research to suggest that the language of communication is very important in teaching and learning. Policy makers believe Ghana’s approach will improve learning as young learners firmly grasp concepts at the early stages of their education and also foster cultural pride and patriotism.

A former minister for education, Professor Naana Opoku Agyeman, has attributed Ghana’s underdevelopment issues – notably extreme poverty and income growth – to the use of English as the only medium of instruction in the lower primary schools. The argument is that this impedes learners’ active participation in the teaching and learning process which, in turn, has negative repercussions on their future learning.

We wanted to find out what ordinary Ghanaians thought about the debate. Our study found that many parents were not happy with a mother-tongue based bilingual policy where young learners began with a familiar local Ghanaian language and gradually introduced to the English language.

Respondents also identified practical difficulties in optimising the module. The difficulty is that Ghana has 11 languages that can be written and studied at this level. For the policy to fully work, teaching materials would have to be designed and published in each of these languages. Parents were not convinced that this had happened, or that the right teaching resources were in place.

Our findings also indicated that the hostile response from parents to the policy was borne out of poor communication.

The Study

Ghana introduced the National Literacy Acceleration Programme in the 2009/2010 academic year. This was after it was discovered in a baseline study that only 18% of third grade pupils could read text in their school’s Ghanaian language. This followed a 2007 assessment that showed that, at grade six, 26% of pupils had minimum competency in English.

Research has shown that quality education is best achieved when it is transmitted in a language familiar to the learners. Researchers suggest that the choice of language of instruction in schools, especially in the early years, is critical for achieving educational outcomes.

Ghana’s programme specifies that a familiar local language – the most common Ghanaian language in the school’s community – is used for academic instruction during the first five years of schooling – from Kindergarten to Primary 3, and that teachers introduce children to English language as part of the curriculum.

From Primary 4 upwards, the medium of instruction transitions to English for the rest of the child’s education. Eleven major languages (Akuapem Twi, Asante Twi, Dagaare, Dagbani, Dangme, Ewe, Fante, Ga, Gonja, Kasem, and Nzema) have been selected to be used alongside English. Schools can select any one of these languages in addition to English for its medium of instruction, depending on its location and learners’ proficiency in the language.

The goal of the policy is to move children gradually to English as a medium of instruction and to recognise their rights as stipulated in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. It is supposed to help them succeed academically and take pride in their heritage.

What next

We found that Ghanaians opposed the bi-lingual programme because they felt the country lacked the teaching and learning resources to make it work. A very large proportion of teachers are not equipped to teach reading in a mother tongue language. This is true even if they are fluent in a language.

Our findings clearly show a need for further training to make the current system work. Teachers on the module require follow up support and a consistent refresher programmes.

The support of parents and the general public is also essential if the policy is to work. More sensitisation needs to be done to help them understand the benefits of the policy.

There are several benefits – social as well as cultural – inherent in the mastery of a local language for children. They associate and socialise better if they are able to converse in a shared language.![]()

Joyce Esi Bronteng, Lecturer of Education, University of Cape Coast; Ilene Berson, Professor of Education, University of South Florida, and Michael J Berson, Professor of Social Science Education, University of South Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.