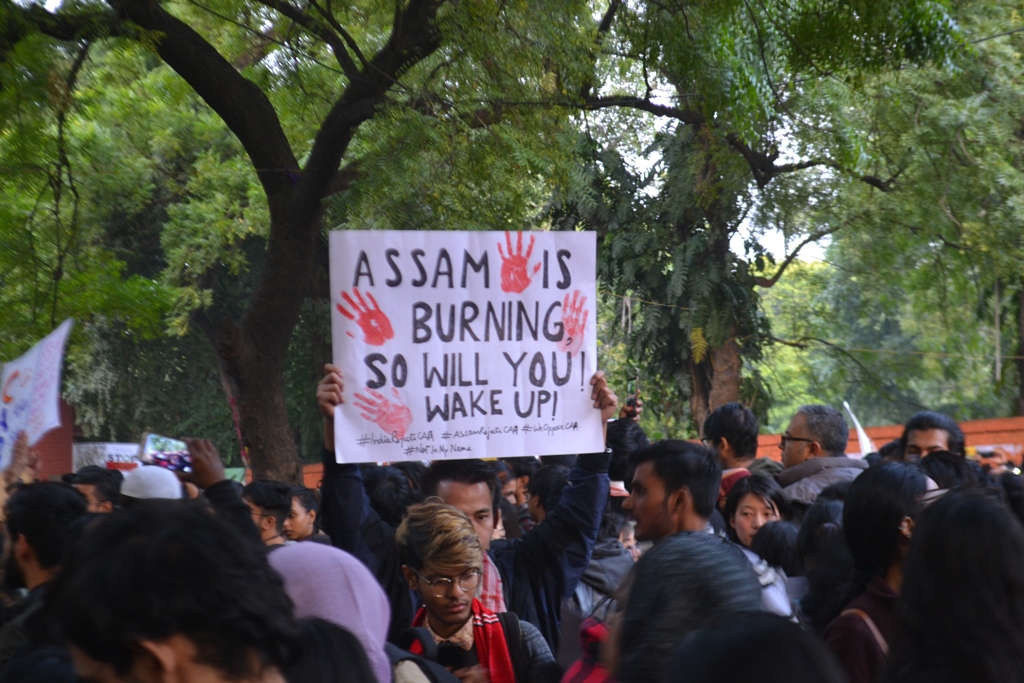

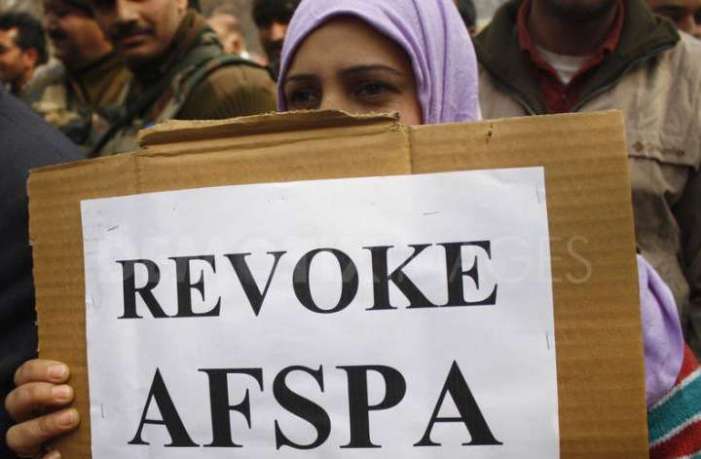

On the evening of 11th December, a fellow-researcher and I engaged in a lengthy discussion regarding the implications of the Citizenship Amendment Bill. I have previously worked on Bhupen Hazarika’s songs of the Assam Movement while he has written his MPhil on the Nellie massacre (1983); hence the Bill was naturally a point of interest to both of us. We spoke for over half an hour and the bottom line that we arrived at was how passing of the CAB will cause disaster, larger than what the fallouts of the Assam Movement expressed. The impending doom still seemed like a distant reality. There were such massive rallies and citizens’ protests in Assam on 10th of December that passing the CAB looked like a very unpopular choice to make. And, of course, like any citizen who believes that democracy runs on the will of the people, for the people and by the people, I did not think the Government would take such a decision in such great haste. An hour later, I was meant to find out. My cell-phone beeped continuously and frantically of news notifications; when I checked there were over eight of them- “CAB passed in the Rajya Sabha”, “Indefinite Curfew imposed on Guwahati”, “Protests erupt in Dispur”! It caused a chaos. I didn’t know what to do first, read the news articles or call my family. Suddenly the impending doom became a real disaster. The worse, however, had still not begun. It was on the 12th of December that the real face of state oppression revealed. While we, the ones away from home watched in horror, our families struggled to stock ration for the ‘indefinite’ curfew. Examinations got cancelled, students were out on the streets defying curfew. Police started detaining and arresting protestors; by evening they started open firing at various places. University hostels were under siege, their gates locked from outside or raided by plain-clothed police at odd hours. We even heard news of firing inside a boys’ hostel of a prestigious engineering college. The internet ban which was supposed to be lifted after 48 hours has, meanwhile, been extended to another 48 hours. It is, in many ways, a replication of what was done to Kashmir (that continues even after 134 days).

But this article is not only about what I am feeling. It is an attempt to tell people what actually is the cause of unrest in Assam right now. A lot of people, not belonging to Assam or any North-Eastern state have come up to me (and other Axamiyas) with a general complaint- “Isn’t refusing the CAB xenophobia on your part? What is the big deal in letting our Bengali brothers from Bangladesh or Hindus from Pakistan come and stay in our country on humanitarian grounds?” To answer this question and understand why exactly Assam so upset right now, we need to go back to a series of events that marked the years 1979-85- famously referred to as the ‘Assam Movement’. It was an agitation under the leadership of the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) and All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) based on four significant points- a) Against illegal immigration of ‘foreigners’-mainly from Bangladesh and Nepal- into Assam/India. b) Against participation of these ‘foreigners’ in the electoral process of Assam/India. c) Demand for deportation of all the illegal foreigners and d) as an effort to protect the distinct identity of the people of Assam against the threat posed by the ‘foreign’ nationals (Hussain 1993: 7).

If the population growth of Assam in the years 1900-1980 is observed, it is seen that the rise of population in Assam has always been higher than the national average. This indicates that a large number of people have been immigrating since 1900. The Constitution of India states that the people who have migrated to India from Pakistan before 26th July 1949 have automatically become Indian citizens. But for the migrants who have come after that, immigration of any sorts had to take place through a prescribed legal process. Nevertheless, millions of Hindus and Muslims from East Pakistan (and Nepal) continued to infiltrate into Assam even after that. In 1971 alone, during the Bangladesh war, around one million Bangladeshis moved into Assam. Some of them returned but a sizeable population remained back. This is visible in the increase in the voter percentage by 10.42 percent between the years 1970-71. Again in 1974, Bangladesh experienced a food shortage leading to mass migration of people into Assam. Following that spate, the voter percentage increased by 10.33 percent in 8 months in 1977. Migration during those months were estimated to be at the rate of around 7500 persons per day (Das 1982: 45). This altered the demographic mixture of Assam significantly.

The increase in immigration had impacts on the various aspects of the Axamiya society- be it economy, ecology or the social structure of Assam. There was a steep rise in unemployment. Also, Assam had already been suffering from underproduction of food from 1957. With increased immigration, the land under cultivation had not increased but the population had doubled. The agricultural labourers’ wages also depressed, seriously affecting the already deteriorating conditions of the indigenous unskilled labourers. Ecologically, as most of the immigrants from Bangladesh settled in the ‘Char’ lands (wetlands) of the Brahmaputra River, using them as spring boards to secure a permanent settlement in the forest lands, the birds and aquatic life on the chars were severely affected. The vast char areas, marshy lands, forests, pastures significantly reduced in Assam as most of them were being used up by the immigrants for settlement. Since 1951, Assam had lost an estimated 41.5% of forest land to immigrants (Das 1982: 48). The sufferers in all cases had been the local Axamiyas. In case it hasn’t become clear yet, Axamiya is a cultural identity. It is a term used to refer to people who accept Assam as their ‘homeland’, regardless of linguistic, ethnic or religious identity.

There developed a serious concern that the indigenous people of Assam would be reduced into a minority if the immigration of ‘non-Indians’ into Assam is not checked; echoing fears of becoming a minority in one’s own homeland like the indigenous people of Tripura.

In view of this increasing influx of illegal immigrants, particularly from Bangladesh, the Axamiya demanded for their deportation. The AASU had demanded the detection and deportation of foreign nationals as early as the Bangladesh war in 1971 and again in 1974. The situation intensified in 1979 when requirements of fresh elections and a revision of the voters’ list revealed more than 45,000 confirmed cases of illegal entries into the voters’ list. This was an alarming discovery. Thereafter, to safeguard the interests of the local ethnic groups that were constitutionally entitled to exercise their voting rights, a mass movement or a ‘drive-out foreigners’ campaign ensued. By December 1979, Assam came under President’s rule and the legislature was kept under suspension.

By the end of 1980, there were two points on which the leadership of the Movement and the government agreed – (a) 1951-61 entrants should not be deported. (b) All the post 1971 entrants should be deported (Hussain 1993: 123). At one point, the proposal of the leaders was that the entrants of 1961-71 should be shared by all the states. The government refused that proposal. After six years of unrest, disagreements and confusions, the leaders of the movement finally agreed to sign a MoU with the Government of India on 15th August, 1985- the Assam Accord. With the signing of the Accord, both the parties came to a mutual agreement regarding the cut-off year for detecting foreigners. 1966 was decided upon as the cut-off year for detecting foreigners in Assam /India and 1971 was recognised as the cut-off year for deporting them. Those who entered Assam between 1st January 1966 and 24th March 1971 would be detected, allowed to stay in Assam and defranchised for 10 years. Those who entered from across the international border after 24th March 1971 would be deported (Hussain 1993:154).

Now, the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, [1955, 2016, 2019] (now an Act) provides eligibility of Indian citizenship to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi and Christian religious minorities from the neighbouring countries of Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. Under the amendment of 2019, migrants who have entered India from these countries (and the above religious communities) by December 31, 2014 are now eligible to apply for Indian Citizenship. Moreover, the residence requirement for naturalization (legal act of acquiring citizenship of a country one migrates to) for these migrants has also been reduced from 11 to 5 years.

What validity does the Assam Accord and its cut-off dates for ascertaining illegal immigration hold in that case? None. Undoubtedly, that leaves Assam wondering if its six years of struggle went in vain. Yes, CAA is clearly communal in nature. And that will affect Assam and the Axamiya community unequivocally. In fact, one of the main fallouts during the Assam Movement was its deviation into debates of language-based and religion-based identity. The emergence of ideologies distinguishing a Hindu as a ‘refugee’ from a Muslim as an ‘immigrant’ provided impetus to two extreme fundamentalist groups- Rashtriya Swyamsevak Sangh (RSS) and Jamat-Islami Hind (JIH)- to enter into the politics of the movement. Similarly, there were isolated incidents of violence against Bengalis in various parts of Upper Assam. The movement began to dissolve; it crumbled into pieces as supporters began to be divided into factions. By and large, the movement began portraying an ‘anti-Muslim’ and ‘anti-Bengali’ image instead of an ‘anti-foreigner’ mode. Unfortunately, that is a fallout this second wave of movement in Assam is also vulnerable to. In certain areas, Bengali-speaking residents have been abused as ‘outsiders’. And it is highly condemnable.

The main point, however, is that illegal immigration, be it of any religion or language, has to be stopped. While the entire country is fighting against the communal nature of this Act and opposing it in favour of safeguarding the Secular ethic of our Constitution, Assam also fights for safeguarding its economy, society and identity. The numbers and data stated above are based on research in the region over years, and they are alarming! The indigenous population of Assam are terrified. Muslim Bangladeshi, Hindu Bangladeshi or any other foreigner-the Brahmaputra Valley cannot take any more of them. Hence, they are out on the streets defying curfews, defying Section 144 and police brutality. For some, this might look like xenophobic jatiyotabaad (ethnic nationalism). Maybe, in certain forms it is. But without being an Axamiya, what identity would we be left with? Yes, I stand against CAA as an outright violation of secularism and selective marginalization of a community based on religion. I, too, am an Indian Muslim. But amidst all these, I urge you all to remember Assam in its lonely battle to safeguard its economic, cultural and ethnic identity as well. Illegal immigration is a serious issue faced by the North-eastern states ever since independence. Political parties have come and gone out of power promising us a solution. Our economy, tribal culture, identity and nature are suffering. The periphery has carried this burden in many more forms that the mainland might even imagine. And its time, you stood for our rights.

Sabiha Mazid is a research scholar pursuing her Ph.D in Sociology at J.N.U.