The Spirit of Socratic Dialogue

Is it possible to be dialogic, and convey deep philosophy in a manner that touches one’s soul? As Arvind Gupta—a distinguished educationist and pedagogue—engages with these three booklets and celebrates their spirit, the relevance of Socratic dialogue becomes clear.

The New Leam booklet series: (i) What does life-affirming education mean?; (ii) The significance of liberal arts in our times;(iii) A dialogue on peace in a violent world.

Arvind Gupta did B.Tech from IIT Kanpur (1975). He shares his passion for books and toys through his website www.arvindguptatoys.com

Socratic dialogue is a process where a facilitator helps a small group find answers to universal questions (What is happiness? What is the meaning of life? What is the purpose of education?). Compared to monologues, lectures and sermons the question-answer method still retains its relevance and charm in critical enquiry. Here the seeker poses serious questions which plague him, and the more experienced, wiser person gently throws light on them, illuminates them, and helps the person see a pattern in his own experiences. There are no black and white, no definitive answers; but it widens the perspective and shows the process of interconnectedness in all its glory. One question leads to another. After a spate of question-answers the seeker is able to see the problem more clearly, with all its complexities and nuances, and arrives at his own answers.

All the three booklets under review “The significance of liberal arts in our times”; “What does life-affirming education mean?”; and “A dialogue on peace in a violent world” have been written in a question-answer form. Bereft of any jargon and jingoism, they have been written simply in a very captivating style so that they are accessible to very ordinary people. They require no prior reading or scholarship. It reminds me of the “survival guide” comic strips of the 1970s by Yona Freidman which endeavored to help the poor across the world earn a living by turning “waste into wealth” assuring them of livelihood without spending cash. That information was made accessible to “unschooled” people through simple drawings with little text (http://arvindguptatoys.com/arvindgupta/environ.pdf). These cartoon strips became a rage and were serialized in over 400 newspapers and magazines throughout the world. The message was simple which went straight to the heart.

The content of these booklets is very relevant to our times, particularly when violence permeates all aspects of our life, when the state is abdicating its responsibility towards basic education and health, and all kinds of charlatans and politicians are jumping into the fray to make a quick buck.

2500 years back, the Buddha asked a fundamental question: ‘ First decide, do you wish to work for LIFE or for DEATH?’ This very profound question still stares us in the face. We need to make choices, often stark choices—whether we wish to work in centralized, authoritarian, elitist schools or help government schools where the poor send their kids. As journalists, do we wish to cover the Lakme Fashion Show or report about farmers’ suicides? After Fukushima, should India set up more nuclear plants? Do we have the right to kill others in the name of national pride, language, religion, caste? Should the country’s best talents be used to further strengthen the military-industrial complex, or fulfill the basic needs of our people? Sadly, today 40% of all research in the world is geared towards designing and developing more powerful weapons – not to ameliorate human suffering.

Sir Martin Ryle was a British astrophysicist and Noble laureate. After seeing the horrors, bloodshed and carnage of WW2 he decided to switch to astronomy – a branch of science far removed from human intrigues and foibles. Six months before his death in Oct 1984 he wrote what is now famous as Ryle’s Last Testimony:

At the end of World War II I decided that never again would I use my scientific knowledge for military purposes; astronomy seemed about as far removed as possible. But in succeeding years we developed new techniques for making very powerful radio telescopes; these techniques have been perverted for improving radar and sonar systems. A sadly large proportion of the PhD students we have trained have taken the skills they have learnt in these and other areas into the field of defense. I am left at the end of my scientific life with the feeling that it would have been better to become a farmer in 1946. One can, of course, argue that somebody else would have done it anyway, and so we must face the most fundamental of questions.

On July 25, 1960 D. D. Kosambi delivered a lecture to the Rotary Club of Poona titled ATOMIC ENERGY IN INDIA. In his note Kosambi asked a fundamental question – In India we sweat all the time in the harsh sun, why don’t we do something about it? Instead of chasing atomic energy, India badly needs solar energy. Homi Bhabha – Kosambi’s boss at the TIFR— didn’t like this, and ultimately Kosambi had to quit the TIFR for asking an honest question. 56 years later when Germany has shut down all nuclear plants, and produces one-third of its energy using sun and wind, Kosambi stands vindicated.

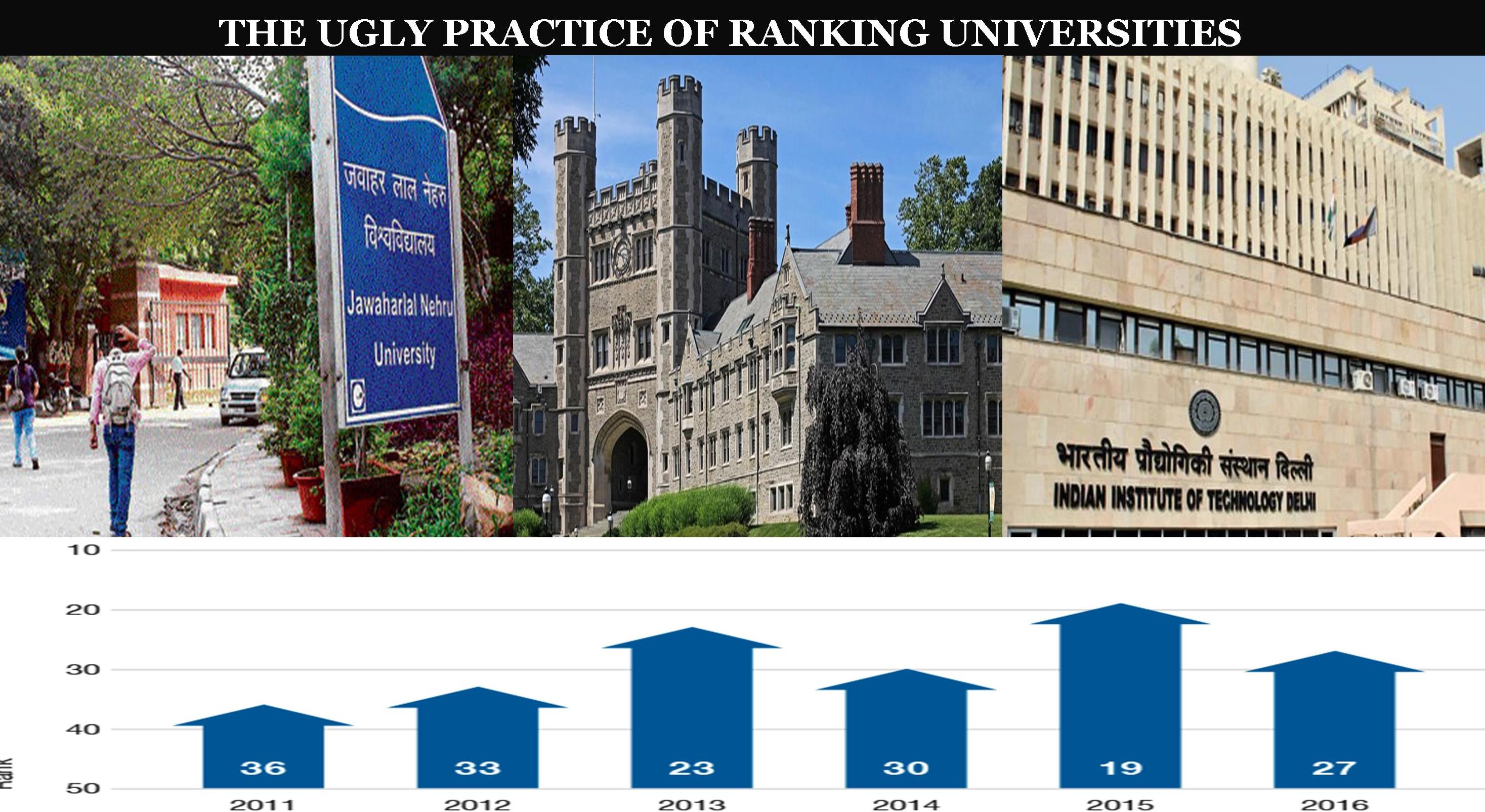

It is in this context that the booklet on the significance of liberal arts is very relevant for our times. While science gives us techniques, arts enriches our values. Several years back the Government of India set up the Yashpal Committee to suggest improvements in our IITs. One of the most significant recommendations of the Yashpal committee was that the IITs must strengthen their Arts Curriculum and there should be writers, historians, artists, musicians, filmmakers, poets in residence. If the IITs don’t beef up their liberal arts departments there is a danger of producing one-dimensional technocrats, who have little understanding of society.

The great physicist and Noble laureate Richard Feynman was once told: “A poet sees great beauty in a rose, but scientists pluck their petals so that they can observe them under a microscope.” To this Feynman replied, “I also appreciate the beauty of the rose, but at a deeper molecular level.”

These booklets have been brought out by a small, compassionate and focused group THE NEW LEAM. These booklets are priced very nominally at Rs 30 each and can be ordered from PUBLICATIONS . There is dearth of such good and rich material on education. There is good reason to hope that a number of good Samaritans will translate them into all the Indian languages.

This article is published in The New Leam, MARCH 2017 Issue( Vol .3 No.22 – 23) and available in print version. To buy contact us or write at thenewleam@gmail.com

The New Leam has no external source of funding. For retaining its uniqueness, its high quality, its distinctive philosophy we wish to reduce the degree of dependence on corporate funding. We believe that if individuals like you come forward and SUPPORT THIS ENDEAVOR can make the magazine self-reliant in a very innovative way.